Treating severe restenosis of a 20-mm balloon-expanding valve after a transapical approach with a risk of coronary obstruction

In this challenging redo TAVI case, an 87-year-old woman presented with severe bioprosthetic valve restenosis and advanced heart failure symptoms, eight years after a previous transapical implantation.

Her frailty, prior surgical approach, and complex anatomy—with low coronary heights and a stent frame extending beyond the sinotubular junction—posed a high procedural risk.

Careful evaluation and multidisciplinary discussion were essential to define a safe and effective treatment strategy.

Authors

Background

Valve-in-Valve or redo-TAVI procedures carry a high risk of coronary occlusion, especially in patients with low coronary heights or high stent frames. The Chimney technique is an effective strategy to preserve coronary flow in these cases.

Case presentation

The patient was referred from an external facility for evaluation of suspected severe stenosis of a previously implanted bioprosthetic aortic valve.

She had undergone transapical TAVI in May 2017. Over the past eight years, she developed progressive NYHA class IV symptoms, including dyspnea at rest, orthopnea, and bilateral leg edema.

Physical examination revealed a grade 2/6 midsystolic murmur and bilateral leg swelling. Body mass index (BMI) was 16.9 kg/m² (weight 40 kg, height 154 cm).

Past medical history

The patient underwent transapical TAVI with a 20-mm balloon-expandable valve (Edwards SAPIEN 3) in May 2017 for severe aortic stenosis. No significant coronary stenoses were observed on coronary angiography.

Her medical history was notable for iron deficiency anemia, managed with intravenous iron supplementation, and a cerebrovascular accident in 2016 without residual neurological deficits. Additionally, she had undergone right total hip arthroplasty.

Examination

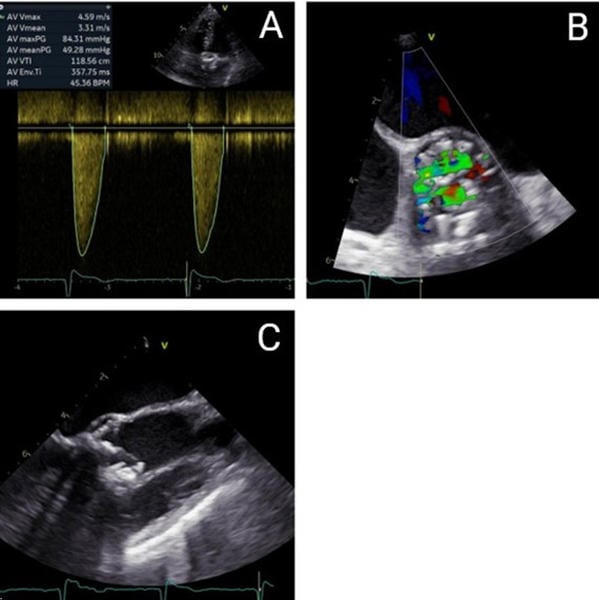

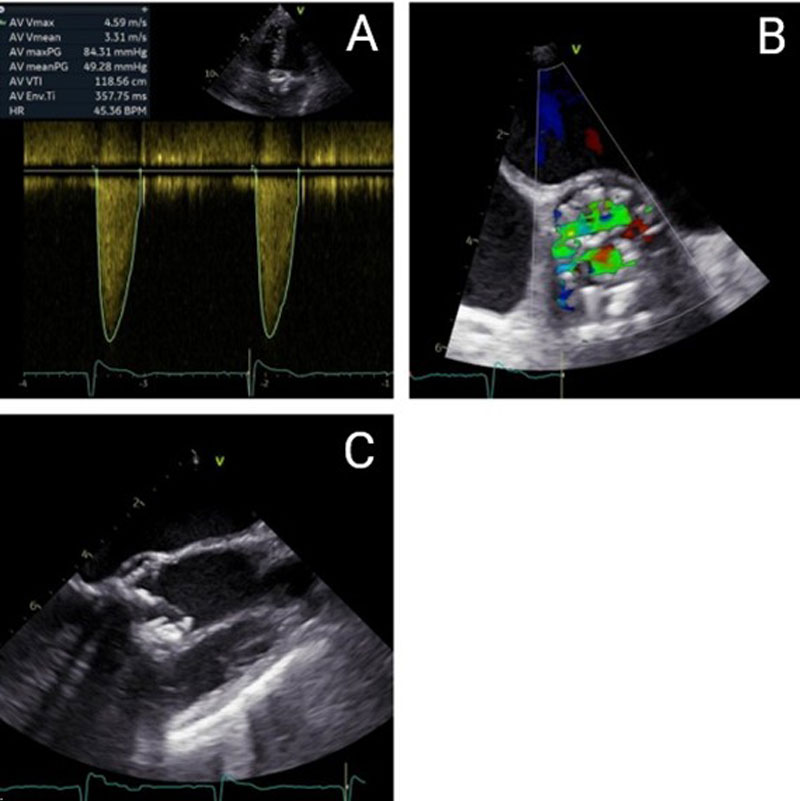

The patient presents with severe degeneration of a bioprosthetic aortic valve, as confirmed by both transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography. Hemodynamic assessment demonstrates a peak transvalvular gradient of 84 mmHg, a mean gradient of 49 mmHg, and a peak velocity of 4.59 m/s, consistent with severe aortic stenosis. The left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) measures 17.3 mm. The aortic valve area (AVA) is calculated at 0.63 cm², with an indexed AVA of 0.47 cm²/m², confirming critical obstruction. Cardiac output is 3.48 L/min, stroke volume index is 56.18 mL/m², and cardiac index is 2.61 L/min/m². Mild aortic regurgitation is also present (Figure 1A), while left ventricular ejection fraction remains within normal limits.

Laboratory testing reveals an elevated NT-proBNP level of 1,662 pg/mL, indicative of increased cardiac wall stress and symptomatic heart failure. Transesophageal echocardiography corroborates severe stenosis with advanced structural degeneration; however, due to pronounced acoustic shadowing and artifact formation, valve planimetry was not feasible (Figures 1B and 1C).

Surgical risk assessment indicates a logistic EuroSCORE I of 41.92 % and a EuroSCORE II of 11.44 %.

Figure 1. Echocardiographic and Transesophageal Echocardiography Findings - (A) Continuous-wave (CW) Doppler on admission. (B) Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), short-axis view, revealed turbulent flow across the bioprosthetic valve on color Doppler on admission. (C) Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), long-axis view showing a heavily calcified bioprosthesis on admission.

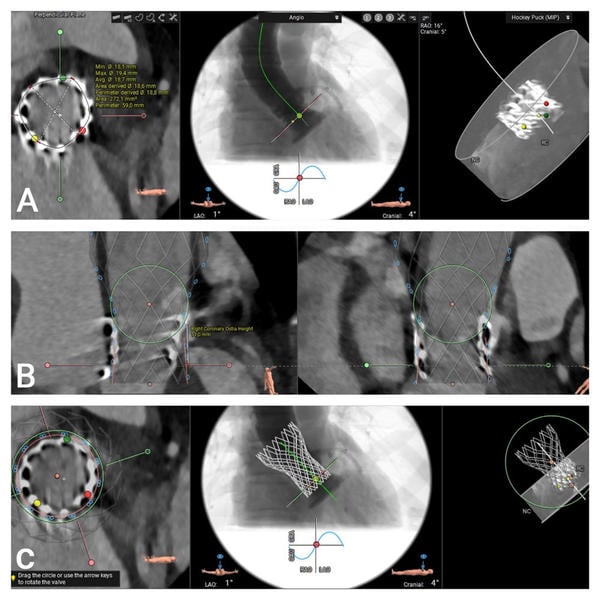

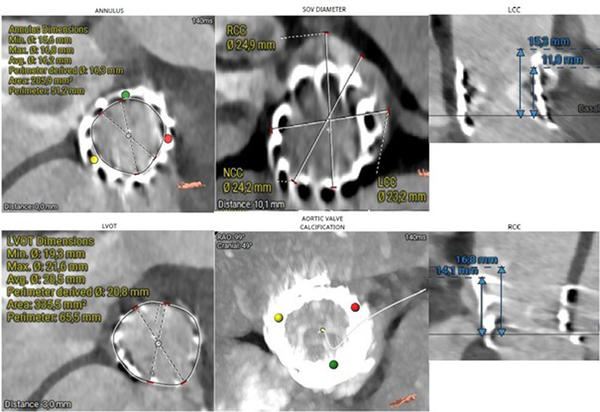

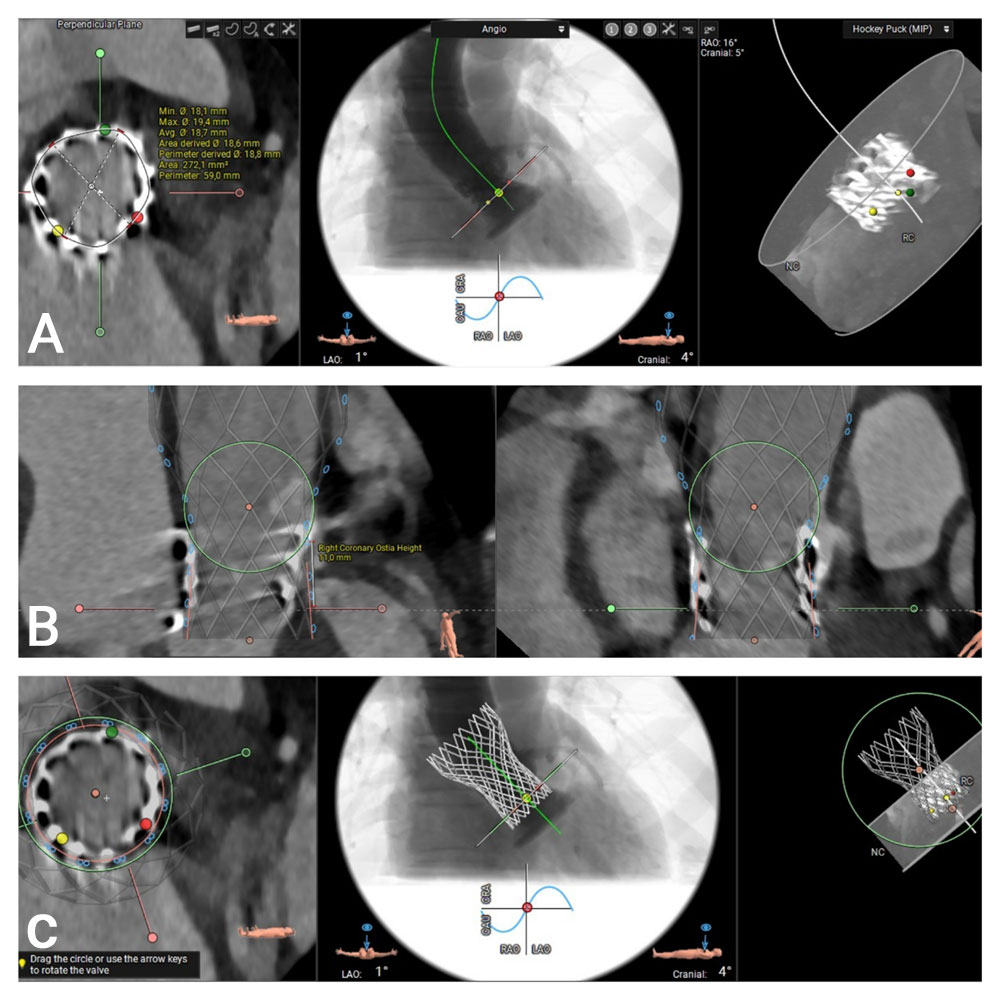

Computed tomography (CT) provides essential anatomical information. Imaging reveals that the outflow edge of the bioprosthetic stent frame extends beyond the sinotubular junction, resulting in complete coverage of the right coronary artery (RCA) ostium, which measures 11 mm in height. The left coronary artery ostium is located at a height of 14 mm, and the aortic annular height is also 14 mm. These anatomical features indicate a substantial risk of coronary obstruction in the setting of valve-in-valve (ViV) transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. MSCT Valve Measurements Using the 3mensio Program:

(A) Measurement of the inflow frame area of the 20 mm Sapien 3 TAVR valve. (B) and (C) 3D visualization of the Virtual Valve in a valve-in-valve configuration and assessment of the height of the right coronary artery.

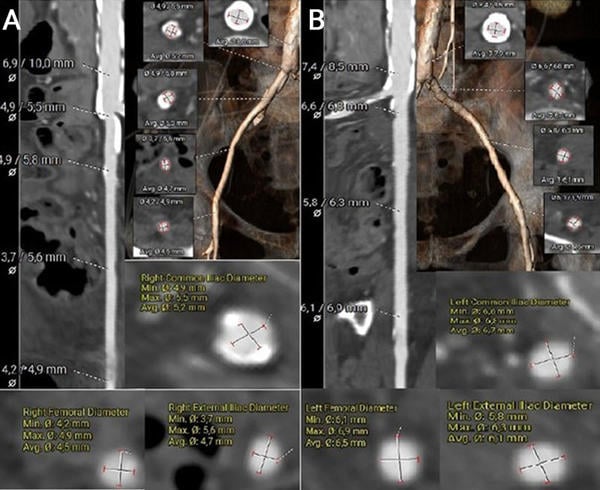

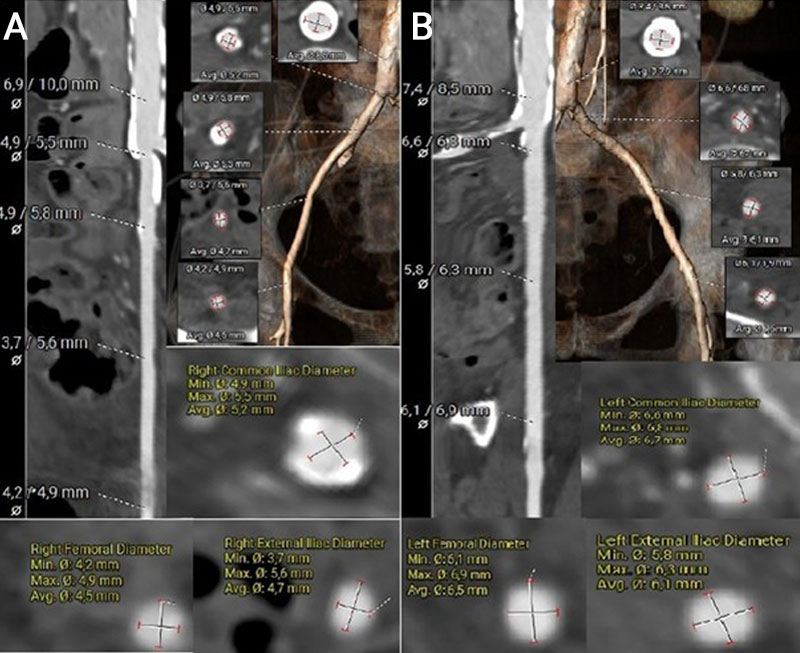

The left common femoral artery measured 6.1 × 6.9 mm, suggesting potential suitability for transfemoral access. In contrast, the right common femoral artery measured 4.2 × 4.9 mm, and the right common iliac artery measured 4.9 mm in diameter. However, the presence of extensive circumferential calcification in the right iliac artery significantly limits its feasibility for vascular access (Figures 3A–B).

Figure 3. MSCT vascular access measurements using the 3mensio software

(A) Measurement and visualisation of the right common femoral artery, right external iliac artery, and right common iliac artery, including a segment of the descending aorta.

(B) Measurement and visualisation of the left common femoral artery, left external iliac artery, and left common iliac artery, including a segment of the descending aorta.

Heart Team decision and procedural planning

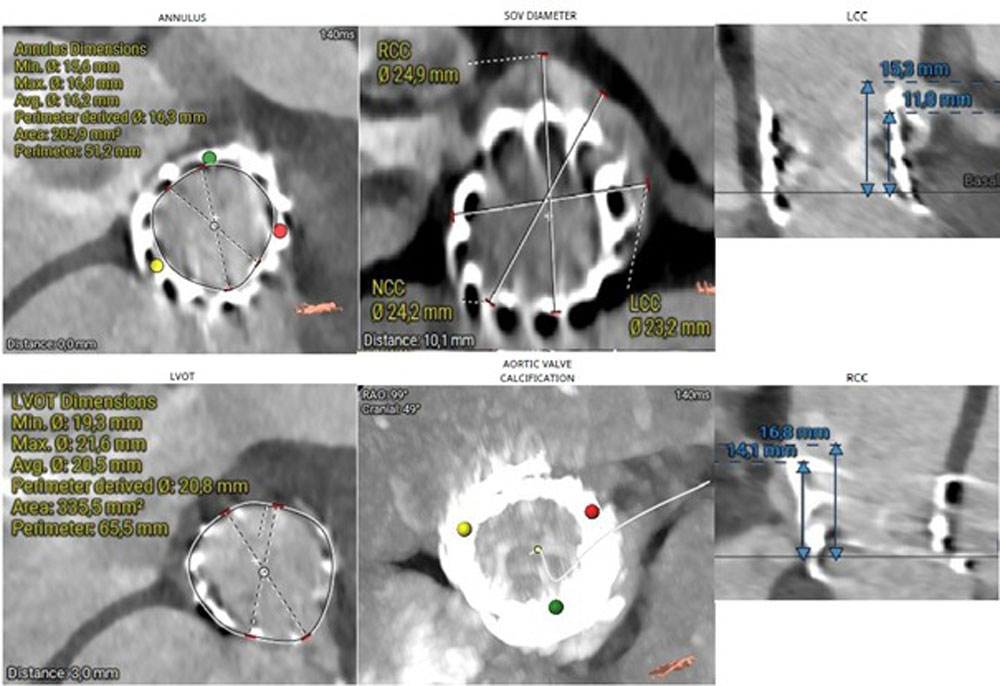

Following a multidisciplinary Heart Team discussion, the patient—given her advanced age, frailty, EuroSCORE, and previous transapical TAVI—was deemed suitable for redo TAVI. Significant LVOT calcification and a small LVOT diameter precluded the use of a balloon-expandable valve. A self-expanding intra-annular prosthesis was not considered due to limited institutional experience. The use of a self-expanding supra-annular valve was associated with a high risk of left coronary artery obstruction. After careful evaluation of the anatomical and procedural risks (Figure 4), transfemoral TAVI was performed using a 23-mm self-expanding supra-annular prosthesis (Medtronic Evolut FX+) with a chimney technique to protect coronary flow.

Figure 4.MSCT measurements using the 3mensio software

Step-by-step implantation

Vascular access was obtained under ultrasound guidance, with bilateral common femoral artery punctures performed. Additional right radial artery access was established for placement of a pigtail catheter. A 14F Medtronic Sentrant introducer sheath was advanced into the left femoral artery without complication. An 18F Manta vascular closure device was pre-deployed in anticipation of large-bore access closure.

For the initially implanted Sapien prosthesis, commissural alignment was not assessed, and CT verification was not performed, given the absence of coronary artery disease. In contrast, for the subsequently implanted Evolut prosthesis, commissural alignment was achieved using the “hat marker” and shaft rotation (HASH) method in combination with the cusp overlap technique. The hat marker was oriented toward the greater curvature of the descending aorta in the left anterior oblique (LAO) view, with additional shaft rotation performed as required prior to deployment to minimize coronary overlap.

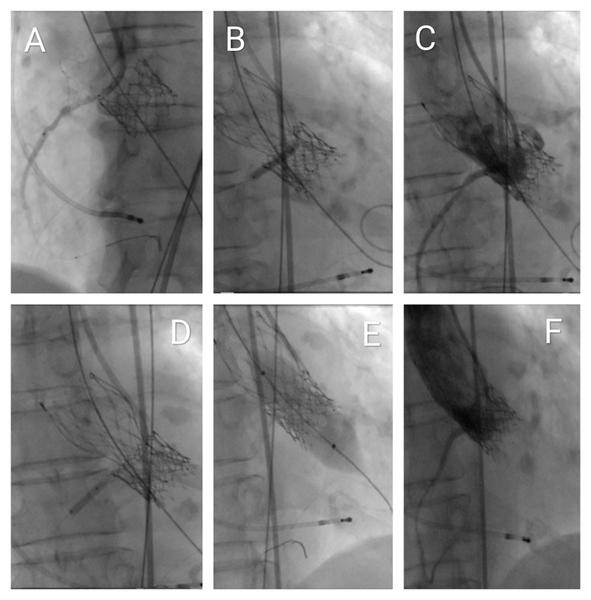

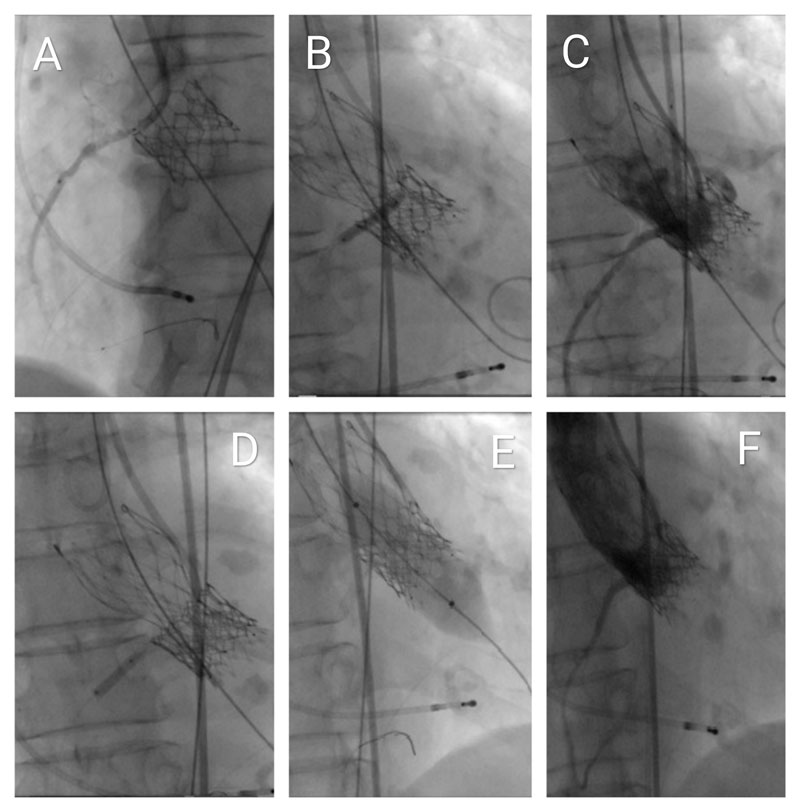

A multipurpose guiding catheter was advanced into the right coronary artery (RCA) ostium, and a Hi-Torque BMW Universal II coronary guidewire was positioned distally. A 2.75 mm × 23 mm drug-eluting stent was pre-positioned with approximately 1 cm protruding into the aorta as a prophylactic measure for bailout coronary protection using the chimney stenting technique. A shorter stent was selected due to suboptimal backup support (Figures 5A, Video 1). The degenerated bioprosthesis was crossed using a straight Terumo guidewire, followed by advancement of an Innowi wire over the pigtail catheter. A 23-mm Evolut FX+ valve was successfully implanted without prior balloon valvuloplasty. Post-deployment, incomplete valve expansion was noted, accompanied by ST-segment elevation in the lateral ECG leads, indicative of impaired coronary perfusion.

Simultaneous percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) of the RCA was then performed, deploying the pre-positioned stent using the chimney technique (Figures 5B, Video 2). This intervention resulted in resolution of the ST-segment changes and hemodynamic stabilization. Subsequent angiography revealed a distal RCA stenosis beyond the initially placed stent, which was successfully treated with a second drug-eluting stent measuring 2.5 mm × 12 mm (Figures 5C and 5D, Video 3).

Following the initial deployment of the TAVI prosthesis, hemodynamic assessment demonstrated a peak-to-peak transvalvular gradient of 30 mmHg, indicating the need for further optimization. A stent balloon from the prior percutaneous coronary intervention was retrieved and positioned at the coronary ostium. Subsequent post-dilatation of the valve was performed using a 20-mm SIMVALVE balloon (Figure 5E, Video 4).

During post-dilatation, no ECG changes or deterioration of the previously implanted stent were observed. Therefore, the kissing balloon technique was not performed. Final angiography confirmed Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) grade III flow and demonstrated no evidence of paravalvular leak or transvalvular regurgitation. Perfusion of the right coronary artery (RCA) was preserved and appeared satisfactory (Figures 5F, Video 5).

Figure 5. Fluoroscopic visualisation of the interventional procedure

(A) Advancement of the Innowi 35SX wire and positioning of the drug-eluting stent at the ostium of the right coronary artery (RCA), with slight protrusion into the aorta.

(B) Incomplete expansion of the Evolut FX+ valve during implantation and simultaneous PTCA of the RCA for inferior ST-segment elevation.

(C) Coronary angiography of the RCA showing stenosis distal to the first stent.

(D) PTCA performed on the distal RCA lesion beyond the initial stent.

(E) Post-dilatation of the valve using a 20-mm SIMVALVE balloon.

(F) Final aortography via pigtail catheter showing good RCA flow with no valve regurgitation or paravalvular leak.

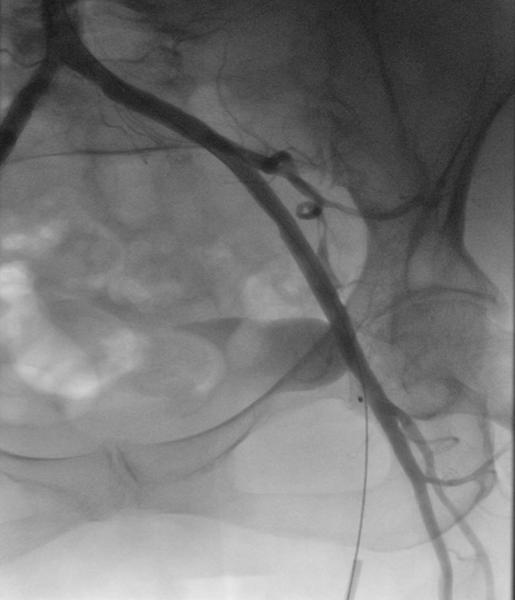

Figure 6. Angiography of the common femoral artery after successful closure with the MANTA device

Outcomes and follow-up

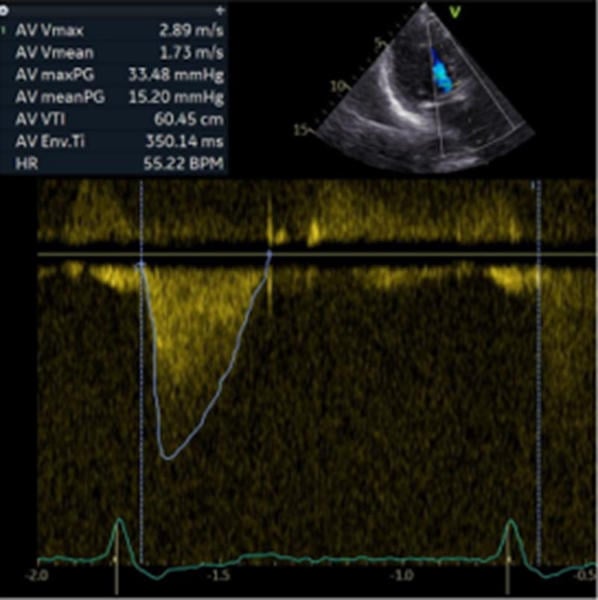

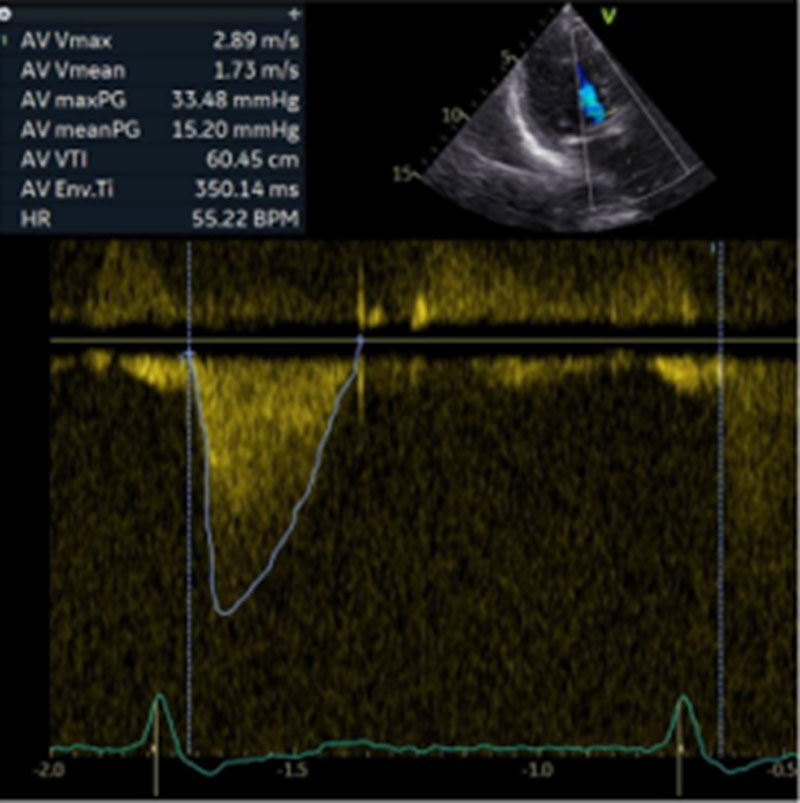

The patient experienced no neurological or vascular complications. Post-procedural echocardiography demonstrated a left ventricular ejection fraction greater than 60 %, a mean gradient of approximately 15.2 mmHg, and no evidence of paravalvular leak. She was discharged to a rehabilitation facility on postoperative day five (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Follow-up with continuous-wave Doppler evaluation after implantation of a 23 mm Evolut FX+ valve

Discussion

Coronary artery obstruction (CAO) remains one of the most severe complications associated with transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), particularly in valve-in-valve (ViV) procedures involving bioprosthetic surgical valves.

Although its incidence is low—necessitating chimney stenting in approximately 0.5 % of contemporary TAVR cases—emergent CAO (eCAO) is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. This underscores the critical importance of meticulous pre-procedural assessment and the implementation of coronary protection strategies in high-risk patients.

In the present case, chimney stenting was successfully utilised as a bailout strategy for acute CAO. The BASILICA technique was not employed due to its technical complexity, limited availability, and the requirement for specialised expertise that is not universally accessible outside experienced centres. First described by Chakravarty et al. in 2013, chimney stenting has emerged as a feasible and effective approach, particularly when coronary protection is pre-planned. Registry data indicate significantly worse outcomes when preemptive protection is not implemented, emphasising the importance of risk anticipation and tailored procedural planning.

In this case, the procedure involved only post-dilatation of the TAVI prosthesis. In such a scenario, the previously implanted stent in the RCA may be at risk of being crushed. Therefore, simultaneous dilatation of both the TAVI prosthesis and the coronary stent—using a kissing balloon technique—can be performed.

Multislice computed tomography (MSCT) continues to play a pivotal role in evaluating the anatomic risk of coronary artery obstruction. Key predictive factors include low coronary ostial height, narrow sinuses of Valsalva, extensive calcifications, and restricted or immobile bioprosthetic leaflets. Despite advancements in imaging, accurate risk stratification remains challenging, underscoring the need for further refinement.

Although chimney stenting can be effective, it is associated with several limitations, including potential challenges in future coronary access and an increased risk of restenosis or stent thrombosis. The procedure is technically demanding, often requiring high-pressure post-dilatation and, in certain cases, deployment of a second stent. In the present case, a second stent was necessary to address residual stenosis. Accordingly, chimney stenting should be reserved primarily for bailout situations or carefully selected high-risk patients, following meticulous pre-procedural planning.

This case further substantiates the accumulating clinical evidence supporting the efficacy of the chimney technique as a viable intervention for mitigating the risk of coronary artery obstruction during ViV-TAVI. In patients with advanced peripheral arterial occlusive disease characterised by severe calcific burden, or those with femoral arterial diameters approaching minimal access thresholds, a streamlined transfemoral TAVI (TF-TAVI) approach incorporating adjunctive strategies—such as serial balloon angioplasty, transluminal vessel preparation, or intravascular lithotripsy (IVL)—may be judiciously considered as an alternative therapeutic modality.

In the International Chimney Registry, involving 12,800 TAVR procedures, chimney stenting was performed in approximately 0.5 % of cases, with low procedural mortality. The absence of upfront coronary protection was the only independent predictor of serious complications, such as death, myocardial infarction, or cardiogenic shock. Pre-procedural evaluation of coronary anatomy and virtual valve modelling is essential to identify risks and plan the procedure. The transfemoral approach is preferred for its minimally invasive nature, and when access is difficult, techniques such as intravascular lithotripsy or atherectomy can facilitate safe transfemoral access.

In summary, chimney stenting continues to serve as a valuable bailout strategy for the management of coronary artery obstruction during TAVR in carefully selected cases. Whenever feasible, transfemoral access should be prioritised, with the use of vascular modification techniques as needed to obviate the need for more invasive alternative access routes.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates the successful use of the chimney technique as a bailout strategy during redo transfemoral TAVI in a patient with high-risk coronary anatomy following prior transapical valve implantation.

Careful pre-procedural planning and coronary protection were essential for procedural success.

Learning points:

- Pre-procedural assessment is critical: evaluate coronary height, sinus dimensions, and simulate valve-in-valve positioning to anticipate the risk of coronary obstruction.

- Chimney stenting is an effective bailout strategy: It can safely restore coronary perfusion in high-risk valve-in-valve TAVI procedures when acute coronary obstruction occurs.

- Expanded redo TAVI feasibility: Medtronic Evolut TAVR systems have received FDA approval for the expanded redo TAVI indication, and this case demonstrates their safety and feasibility.

Conflicts of interest:

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mercanti F, Rosseel L, Neylon A, Bagur R, Sinning JM, Nickenig G, Grube E, Hildick-Smith D, Tavano D, Wolf A, Colonna G, Latib A, Mitomo S, Petronio AS, Angelillis M, Tchétché D, De Biase C, Adamo M, Nejjari M, Digne F, Schäfer U, Amabile N, Achkouty G, Makkar RR, Yoon SH, Finkelstein A, Dvir D, Jones T, Chevalier B, Lefevre T, Piazza N, Mylotte D. Chimney Stenting for Coronary Occlusion During TAVR: Insights From the Chimney Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020 Mar 23;13(6):751-761. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.01.227. PMID: 32192695.

- Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(4):e25–e197. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.018 – Emphasizes the importance of anatomical assessment before TAVI, including coronary height and sinus anatomy.

- Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(7):561–632. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395 – Recommends CT-based anatomical evaluation and highlights the transfemoral route as the preferred access site.

- Blanke P, Weir-McCall J, Achenbach S, et al. Computed Tomography Imaging in the Context of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (TAVI)/Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR): An Expert Consensus Document. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(1):1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.12.003 – Offers detailed guidance on pre-TAVI imaging, including virtual valve modeling and coronary height evaluation.

- Di Mario C, Goodwin M, Ristalli F, et al. A prospective registry of intravascular lithotripsy-enabled vascular access for transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2019.01.211 – Demonstrates the safety and feasibility of using intravascular lithotripsy to improve femoral access in TAVI patients.

- Nardi G, De Backer O, Saia F, Søndergaard L, Ristalli F, Meucci F, Stolcova M, Mattesini A, Demola P, Wang X, Al Jabri A, Palmerini T, Bruno AG, Ielasi A, Van Belle E, Berti S, Di Mario C; on behalf of the Peripheral IVL-TAVI Investigators. Peripheral intravascular lithotripsy for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a multicentre observational study. EuroIntervention. 2022;18(5):e386–e394. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-21-00581.

No comments yet!