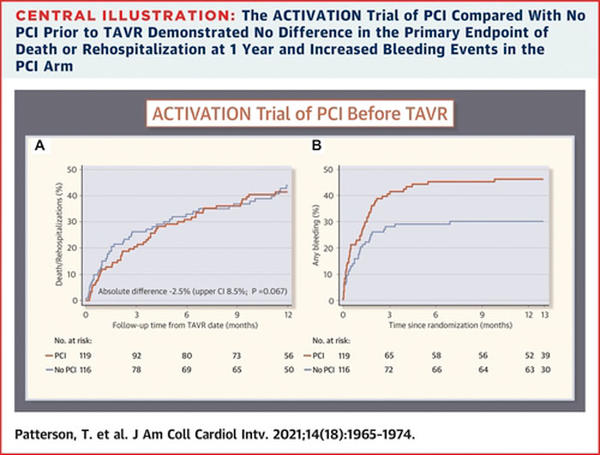

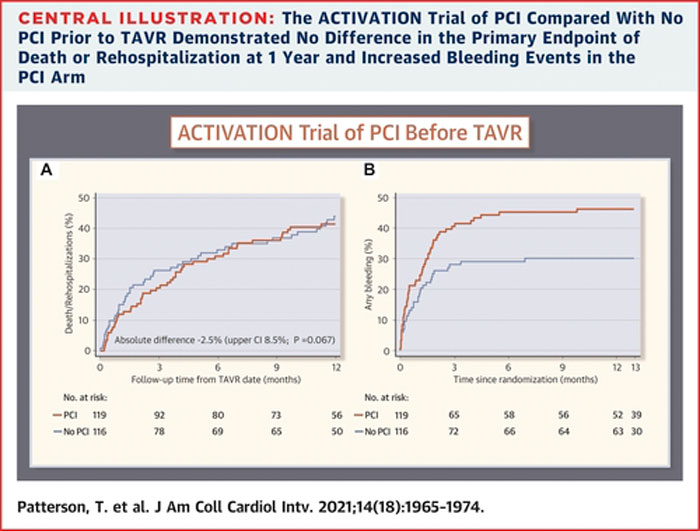

ACTIVATION (percutAneous Coronary inTervention prIor to transcatheter aortic VAlve implantaTION): a randomized clinical trial

Selected in JACC Cardiovascular Interventions by R.A. Kotronias , S. Brugaletta

In conducting the ACTIVATION trial, Redwood and colleagues seek to complement the existing literature with high-level evidence on whether percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) prior to TAVR is non-inferior to conservative (no PCI) management.

References

Authors

Tiffany Patterson, Tim Clayton, Matthew Dodd, Zeeshan Khawaja, Marie Claude Morice, Karen Wilson, Won-Keun Kim, Nicolas Meneveau, Rainer Hambrecht, Jonathan Byrne, Didier Carrié, Doug Fraser, David H. Roberts, Sagar N. Doshi, Azfar Zaman, Adrian P. Banning, Hélène Eltchaninoff, Hervé Le Breton, David Smith, Ian Cox, Derk Frank, Anthony Gershlick, Mark de Belder, Martyn Thomas, David Hildick-Smith, Bernard Prendergast, Simon Redwood on behalf of the ACTIVATION Trial Investigators.

Reference

10.1016/j.jcin.2021.06.041

Published

September, 14 2021

Link

Read the abstractReviewers

Our Comment

Why this study? – the rationale/objective

Severe symptomatic aortic stenosis and significant coronary artery disease coexist in up to 75 % of patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR)1. The clinical approach to treating CAD in this context is variable and has rapidly evolved alongside TAVR practice.

In conducting the ACTIVATION trial, Redwood and colleagues seek to complement the existing literature with high-level evidence on whether percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) prior to TAVR is non-inferior to conservative (no PCI) management.

How was it executed? - the methodology

The investigators conducted, between December 2012 and January 2019, a multicentre, non-inferiority, randomized controlled trial among 235 patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis and angiographically significant CAD accompanied with Canadian Cardiovascular Society class ≤ 2 angina.

Patients were randomly assigned to PCI or no PCI prior to TAVR.

The primary endpoint was the composite of all-cause mortality or rehospitalization at 1 year.

Non-inferiority testing using a pre-specified margin of 7.5 % was performed in the intention to treat and per-protocol treated population.

A range of a priori defined patient-oriented clinical endpoints that included bleeding were also evaluated.

What is the main result?

A routine PCI strategy for significant obstructive CAD in patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis prior to TAVR did not reach non-inferiority when compared to no PCI (difference: -2.5 %; 1-sided upper 95 % confidence limit: 8.5 %; 1-sided noninferiority test p = 0.067).

A routine PCI strategy was associated with higher bleeding complications than no PCI at 1 year (44.5 % vs 28.4 %, HR: 1.66; 95 % CI: 1.07-2.56), yet stroke, myocardial infarction, and acute kidney injury did not significantly differ.

Source: JACC Cardiovascular Interventions

Critical reading and the relevance for clinical practice

This is the first randomized controlled trial in the field of concomitant severe symptomatic aortic stenosis and significant CAD.

At the time the study was conceived, TAVR practice was at its nascency, and the prognostic impact of CAD was contested. The investigators hypothesized that PCI may reduce mortality by reducing the risk of peri-operative haemodynamic instability and impaired ventricular contractility following TAVR.

As ACTIVATION was recruiting, large cohort studies showed that although CAD presence was associated with mortality, this relationship was attenuated after adjustment for confounders and only remained significant in patients with highly complex CAD2.

Importantly, meta-analyses evaluating routine PCI for significant CAD in patients undergoing TAVR showed that a routine angiography-based PCI strategy before or during TAVR conferred no clinical advantage with respect to several patient‐important clinical outcomes1.

In this regard, early observational data suggest that functional assessment of CAD can lead to safe deferral of stenting in up to 74 % of patients with angiographically significant CAD3.

Therefore, as recruitment was ongoing, the clinical landscape shifted considerably such that the trial’s findings are not practice-changing, yet are important in supporting contemporary practice.

In the context of an elderly and comorbid TAVR population at a high bleeding risk, the requirement for dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) following PCI increases the peri-procedural and post-procedural bleeding risk of TAVR.

ACTIVATION participants underwent TAVR on average 2 weeks following PCI whilst on anti-thrombotic therapy and accrued the majority of bleeding complications within 30 days from TAVR.

Indeed, the authors conclude that the use of DAPT may account for the significantly higher bleeding rates noted in the PCI arm. However, the numerical difference in coumarin administration at the time of randomization between the study arms (PCI arm 26.1 % vs no PCI arm 15.9 %) may have also introduced bias against the PCI arm. The latter also highlights the lack of a predefined antithrombotic protocol that introduces considerable clinical heterogeneity.

A further important limitation of ACTIVATION is its early termination due to lower-than-expected recruitment rates. With a final sample size of 235 participants, the study was underpowered for its primary endpoint and yielded inconclusive findings.

Furthermore, if an adequately powered ACTIVATION trial had shown non-inferiority for its primary endpoint, would this suffice to adopt a routine PCI approach, given the reported risk of bleeding and signal of higher AKI rates?

Considering the debatable prognostic relevance of CAD presence in these patients, the higher bleeding risk associated with a routine PCI approach in the trial, and the established association between peri-procedural bleeding and mortality/rehospitalizations4-5, it would not suffice to say that PCI is no worse than no PCI.

A large-scale superiority trial would have been needed to inform clinical practice and begs the question of whether a superiority design would have been a more appropriate study design.

Fortunately, despite the trial’s loss of power, its inconclusive findings are consistent with previous literature.

Therefore, the take-home message following this trial is that a routine PCI strategy in patients with obstructive CAD prior to TAVR is not clinically advantageous and is linked to higher bleeding rates.

As randomized data on physiology-guided PCI in this patient cohort are awaited [FAI-TAVI NCT03360591 and NOTION-3 NCT03058627], an individualized approach to revascularization decision-making factoring in symptomatology, ischaemic and bleeding risk, and procedural considerations (valve choice, future coronary access) may be important.

In the interim, the focus of the interventional community is shifting towards how to perform PCI in TAVR patients.

References

- Kotronias RA, Kwok CS, George S, Capodanno D, Ludman PF, Townend JN, et al. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation With or Without Percutaneous Coronary Artery Revascularization Strategy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(6).

- Snow TM, Ludman P, Banya W, DeBelder M, MacCarthy PM, Davies SW, et al. Management of concomitant coronary artery disease in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the United Kingdom TAVI Registry. Int J Cardiol. 2015;199:253-60.

- Lunardi M, Scarsini R, Venturi G, Pesarini G, Pighi M, Gratta A, et al. Physiological Versus Angiographic Guidance for Myocardial Revascularization in Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2019;8(22):e012618.

- Franzone A, Pilgrim T, Arnold N, Heg D, Langhammer B, Piccolo R, et al. Rates and predictors of hospital readmission after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. European Heart Journal. 2017;38(28):2211-7.

- Kolte D, Khera S, Sardar MR, Gheewala N, Gupta T, Chatterjee S, et al. Thirty-Day Readmissions After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in the United States: Insights From the Nationwide Readmissions Database. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10(1).

No comments yet!