ViV challenges in degenerated sutureless bioprosthesis

Supported by the EuroIntervention Journal

Authors

Clara Fernández-Cordón¹, Mario García-Gómez¹, Akash Jain¹, Marcelo Rodríguez¹, Ana M Serrador Frutos¹, Alberto Campo Prieto¹, Hipólito Gutiérrez¹, Carlos Cortés Villar¹, Sara Blasco Turrión¹, Alberto San Román¹, Ignacio J Amat-Santos¹.

- Interventional Cardiology Unit. Cardiology Department. Heart Sciences Institute (ICICOR). Clinical University Hospital, Valladolid. Spain.

Introduction

The Perceval S sutureless aortic valve was introduced in 2007 as an alternative for high-risk patients, to reduce cross-clamp time and surgical mortality and morbidity. The implantation technique involves three guiding sutures placed 120º apart, placement of the prosthesis in the annulus, and ballooning to ensure valve anchoring, with removal of the guide-threads during ballon inflation1.

As other biological valves, the Perceval is prone to structural valve degeneration. Valve-in-valve (VIV) transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is an attractive and feasible option in this scenario, although there is still little experience2,3.

Case summary

An 81-year-old female patient with history of Perceval S size M (23 mm) bioprosthesis implantation in 2019 presented with decompensated heart failure. Valve degeneration with severe stenosis and moderate intravalvular regurgitation, with no paravalvular leak, was noted. The Heart Team discouraged redo surgery, and she was evaluated for TAVI. Computed tomography (CT) showed severely calcified iliofemoral arteries (minimum diameter 3 mm) and bilateral subclavian occlusion, along with a low take-off of the left main (height 6.4 mm) and a valve-to-coronary (VTC) distance of 2.4 mm. Considering these measurements and the expansion capacity of the Perceval after implantation of the TAV, the risk of coronary obstruction was high. The bioprothesis true ID was 19.5-21 mm, and stent ID 23 mm. Transcaval ViV TAVI with left BASILICA (bioprosthetic or native aortic scallop intentional laceration to prevent iatrogenic coronary artery obstruction) using a balloon-expandable valve was planned. A Myval 23 mm was chosen according to CT analysis and ViV Aortic app.

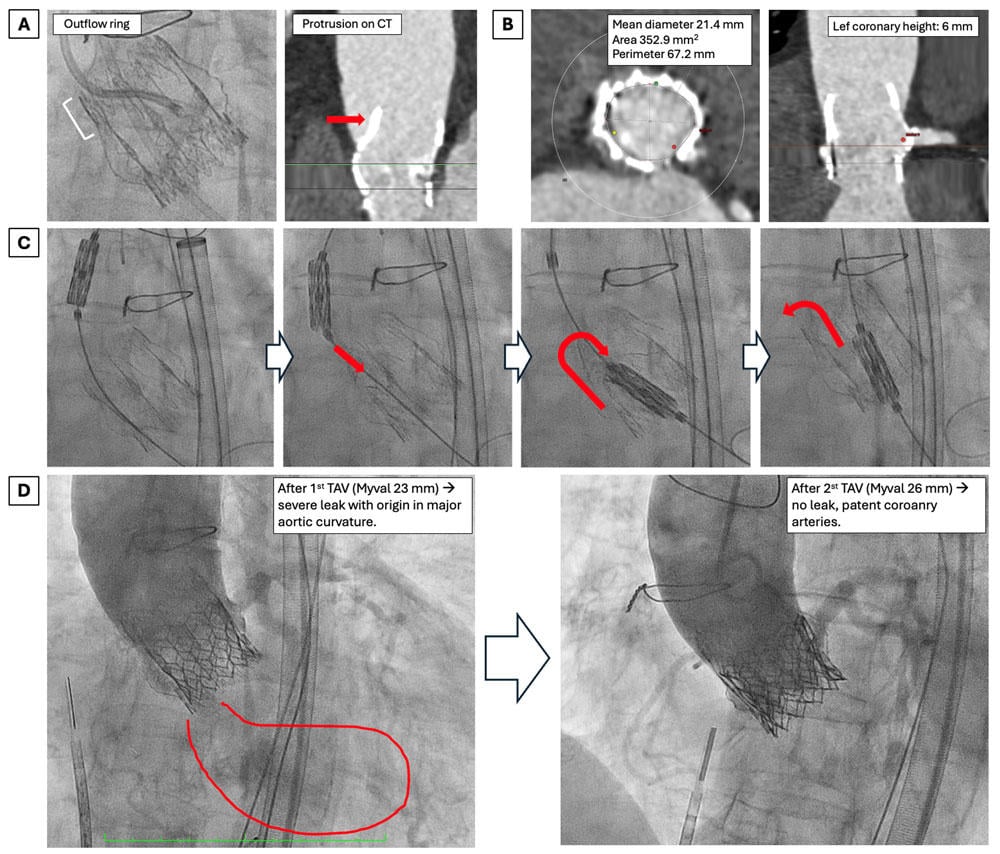

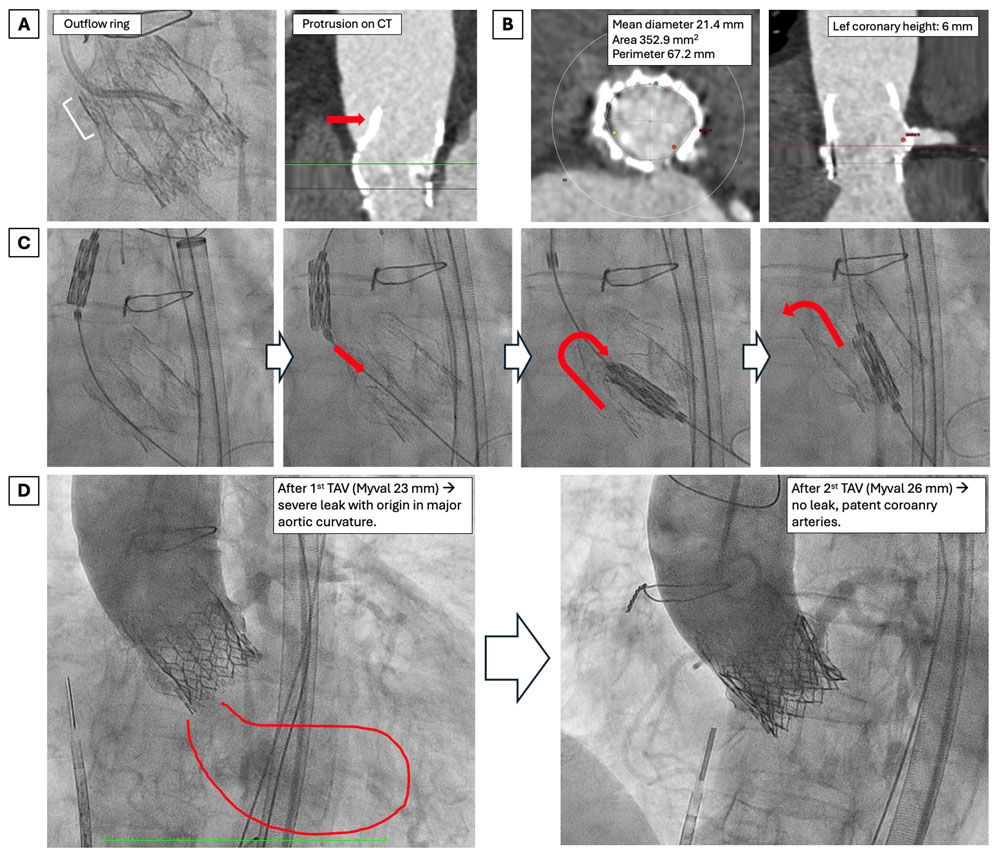

Transcaval puncture was performed from the right femoral vein using an Astato 20 guidewire, with subsequent placement of a 24 Fr long Dryseal introducer. BASILICA was guided by intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) and performed as per conventional technique, with successful tearing of the left coronary leaflet. At this point, poorly tolerated acute severe aortic regurgitation (AR) occurred. It was hard to advance the Myval into the annulus, as it collided with the outflow ring of the Perceval, causing it to crush and fold inwards. A snaring maneuver was considered but not performed due to hemodynamic instability, as it can be time-consuming. After some Safari wire manipulation, the Myval crossed the annulus, with the Perceval seemingly going back to its prior degree of expansion. Deployment of the Myval 23 mm was performed, but there was persistent hemodynamic instability. Both coronary arteries were patent, but severe paravalvular leak (PVL) was noted on angiography and confirmed by bedside transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE), predominantly at the external aortic curvature where the Perceval crushing had occurred.

PVL persisted despite postdilatation with a 24 mm balloon. We hypothesized that Perceval dehiscence/instability during crossing, plus some degree of TAV undersizing and inadequate sealing (given the Perceval ability to expand without valve fracture), could be the underlying mechanisms of PVL.The patient was very unstable, forcing us to make a timely decision. We decided to implant a second, intentionally oversized Myval 26 mm valve to account for both potential mechanisms of AR. After the second TAV, PVL resolved completely, coronary arteries were still patent, and hemodynamics improved. Transcaval access was successfully closed with a ductus device, and no vascular complications nor conduction disturbances were noted. See Video 1 for a video summary of the case.

In this case, we describe for the first time how the collision of a TAV device during valve crossing in ViV TAVI can potentially cause instability or dehiscence of the Perceval S sutureless bioprosthesis, contributing to severe poorly tolerated PVL (Figure 1).

Figure 1. (A) Perceval S bioprosthesis and outflow ring protrusion. (B) Cardiac computerized tomography showing annulus dimensions and left coronary height. (C) Sequence showing crushing and inward folding of the Perceval during valve crossing with the Myval TAV. (D) Angiographic result after 1st and 2nd transcatheter aortic valve (TAV) implantation.

This risk had been hypothesised previously in literature3, but its occurrence had not actually been reported2.

Our case highlights several learning points and implications for future procedures:

- outflow ring protrusion should be assessed on preprocedural CT;

- a short-frame BEV TAV might be favored over a self-expandable one in this scenario;

- adjunctive techniques such as a second high-support buddy wire or snaring maneuvers could be considered to facilitate TAV advancement into the annulus;

- if Perceval instability and PVL do occur, the implant of a second, larger size, balloon-expandable TAV device might be used successfully as a bailout strategy.

References

- Shrestha M, Folliguet T, Meuris B, Dibie A, Bara C, Herregods MC, Khaladj N, Hagl C, Flameng W, Laborde F, Haverich A. Sutureless Perceval S aortic valve replacement: a multicenter, prospective pilot trial. J Heart Valve Dis. 2009;18(6):698-702.

- Owais T, Bisht O, El Din Moawad MH, El-Garhy M, Stock S, Girdauskas E, Kuntze T, Amer M, Lauten P. Outcomes of Valve-in-Valve (VIV) Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR) after Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement with Sutureless Surgical Aortic Valve Prostheses PercevalTM: A Systematic Review of Published Cases. J Clin Med. 2024;13(17). doi:10.3390/jcm13175164

- Landes U, Sagie A, Kornowski R. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation in degenerative sutureless perceval aortic bioprosthesis. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 2018;91(5):1000-1004. doi:10.1002/ccd.26576

Conflicts of interest

Ignacio J Amat-Santos is proctor for Meril Life. The remaining authors do not have any disclosures.

No comments yet!