85 results

Impact of complete revascularisation in relation to left ventricular function in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and multivessel disease: a post hoc analysis of the COMPLETE randomised trial

05 Feb 2026

This study represents a prespecified subgroup analysis of the COMPLETE randomised trial, a large, international, randomised controlled study comparing a strategy of complete revascularisation with culprit-only percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and multivessel coronary artery disease (MVD).

The present...

Reviewer

Reviewer

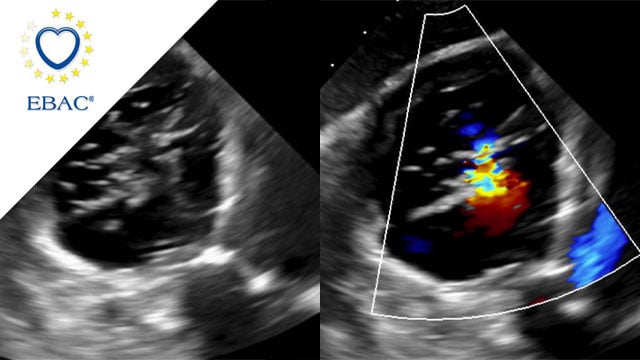

M-TEER with Mitraclip Gen5

03 Feb 2026

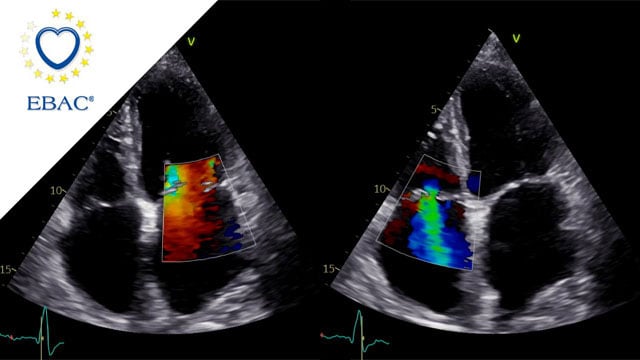

An 83-year-old female patient with HFrEF due to NICM and a history of arterial hypertension and persistent atrial fibrillation was referred with worsening exertional dyspnea, severe functional mitral regurgitation and moderate tricuspid regurgitation.

How would you treat this patient?

Author

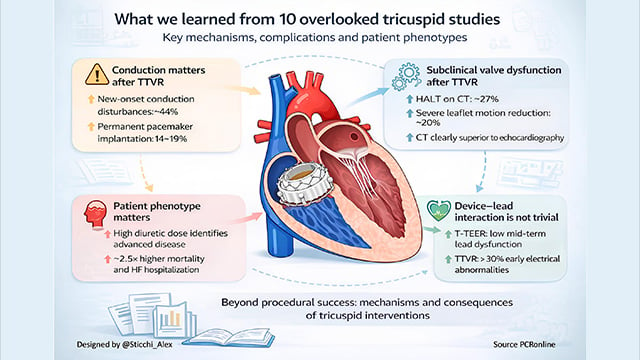

The top ten impactful papers from 2025 on tricuspid intervention we almost missed

13 Jan 2026

Transcatheter interventions have rapidly reshaped the management of tricuspid valve disease, with landmark trials establishing feasibility and early clinical benefit.

Beyond these pivotal studies, a series of less visible but highly informative papers addressed mechanisms, complications, patient phenotypes, and unintended consequences of intervention.

This curated selection highlights ten impactful tricuspid...

Author

How to manage Safari wire entrapment during TAVI with Navitor THV

19 Jan 2026

Safari wire entrapment during TAVI is a rare but potentially serious complication, particularly with sheathless self-expanding valves. In this My Toolkit article, we describe a simple, effective technique using a parallel stiff guidewire to safely retrieve both the catheter and the entrapped Safari wire when performing...

Author

Author

Author

Author

How should I treat a torrential tricuspid valve regurgitation in a young patient who remains symptomatic despite optimal medical therapy?

25 Dec 2025

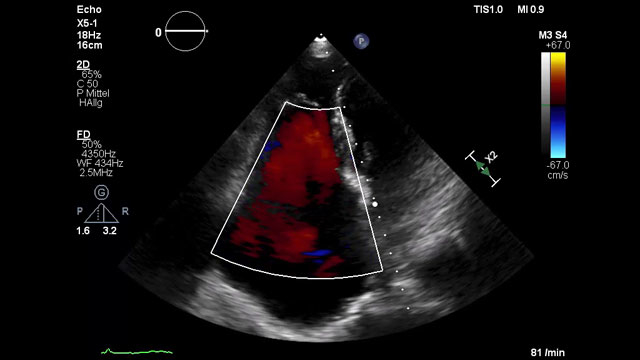

A frail patient presents with worsening NYHA class III dyspnoea and peripheral oedema despite optimal medical therapy. Previously managed conservatively, severe tricuspid regurgitation has progressed to a torrential grade, with right-sided chamber dilatation and complex valve anatomy.

How would you treat this patient?

Author

Author

LAA closure with CT planning: challenging inferior chicken wing morphology

24 Dec 2025

This 77-year-old woman with paroxysmal AF and prior GI bleeding is referred for LAA closure, but CT reveals a shallow, inferior chicken-wing morphology that complicates device selection and planning. How would your Heart Team approach this challenging case?

Author

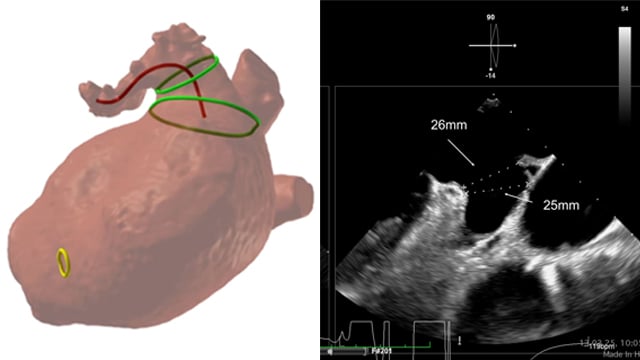

When a surgical valve needs a second life

23 Dec 2025

A 79-year-old patient previously treated with surgical aortic valve replacement was referred after an episode of acute cardiac decompensation. Although clinically stabilised, further evaluation revealed degeneration of the bioprosthesis, and mixed aortic valve pathology.

This case focuses on the diagnostic assessment and the strategic considerations guiding the...

Author

Highlights of science and education in cardiovascular interventional medicine in 2025

22 Dec 2025

Dear Colleagues, dear PCR Companions,

As we welcome a New Year, it is the perfect time to reflect on what we achieved together over the past year - both as a celebration of our collective success and as motivation to continue improving in the year ahead.

2025 was...

Impact of guideline-directed medical therapy on long-term outcome after tricuspid TEER

29 Jan 2026

A 79-year-old woman with advanced right heart failure (NYHA III) was referred after repeated hospitalisations for decompensation despite optimal medical therapy. Echocardiography revealed torrential functional tricuspid regurgitation with suitable anatomy for T-TEER. Given her high surgical risk (TRISCORE 7/12) and borderline pulmonary hypertension, how would you...

Author

Author

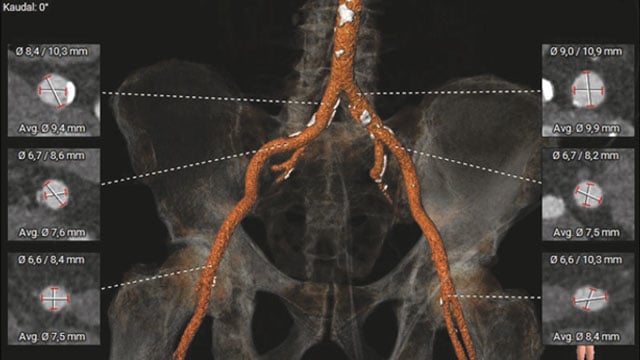

New roads begin where old ones end: a TAVI case

12 Jan 2026

An 85-year-old woman presents with exertional dyspnea and angina, alongside severe paradoxical low-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis, marked mitral and tricuspid valve disease, and two-vessel coronary artery disease. Frailty markers and hostile pelvic anatomy further complicate her profile.

How would your Heart Team approach this challenging case?

Author

Author