24 Sep 2021

Influenza Vaccination after Myocardial Infarction: IAMI

Selected in AHA Journal - Circulation by C. Johnston , K. De Silva

The objective of the IAMI1 trial was to determine whether early influenza vaccination reduces the risk of cardiovascular events in patients admitted with an acute-MI or high-risk stable coronary artery disease in an adequately powered randomized control trial setting.

References

Authors

Ole Frøbert, Matthias Götberg, David Erlinge, Zubair Akhtar, Evald H. Christiansen, Chandini R. MacIntyre, Keith G. Oldroyd, Zuzana Motovska, Andrejs Erglis, Rasmus Moer, Ota Hlinomaz, Lars Jakobsen, Thomas Engstrøm, Lisette O. Jensen, Christian O. Fallesen, Svend E. Jensen, Oskar Angerås, Fredrik Calais, Amra Kåregren, Jörg Lauermann, Arash Mokhtari, Johan Nilsson, Jonas Persson, Per Stalby, Abu K.M.M. Islam, Afzalur Rahman, Fazila Malik, Sohel Choudhury, Timothy Collier, Stuart J. Pocock, and John Pernow

Reference

10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.057042

Published

August, 30 2021

Link

Read the abstractReviewers

Our Comment

Why this study? – the rationale/objective

For many years, there has been a suspected causal link between influenza and cardiovascular disease. This has been supported by registry studies highlighting increased mortality from cardiovascular events during influenza epidemic periods compared to non-epidemic periods2.

A number of observational studies and single-centre, underpowered RCTs have also suggested a protective effect of influenza vaccination on cardiovascular events3,4,5. For this reason, both the ESC and AHA/ACC list influenza vaccination as a class I, level of evidence B recommendation in their secondary preventative guidelines for coronary artery disease6,7. However, the mechanism behind the protective effect and optimal timing of vaccination remains unclear.

The objective of the IAMI trial was to determine whether early influenza vaccination reduces the risk of cardiovascular events in patients admitted with an acute-MI or high risk stable coronary artery disease in an adequately powered randomized control trial setting.

How was it executed? - the methodology

In this multi-centre, international trial, participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1, double-blind approach to receive either influenza vaccine (n = 1,272) or placebo (n = 1,260) within 72 hours of PCI or during the index hospital admission.

Participants were eligible if they had presented with an acute coronary syndrome (either STEMI or NSTEMI) and had undergone coronary angiography or PCI.

To optimise recruitment, changes were made to the enrolment criteria during the trial to include patients with high-risk stable coronary artery disease (age > 75 yrs with at least one additional risk factor).

Patients were excluded if they had received or intended to receive the influenza vaccination during the ongoing influenza season.

Participants were allowed to obtain influenza vaccination outside of the study which permitted a degree of crossover from the placebo arm to the vaccine arm.

The primary endpoint was the composite of all-cause death, MI, or stent thrombosis at 12-months post-randomisation. The components of the primary composite endpoint plus cardiovascular death were considered key secondary endpoints. These were assessed by telephone interview with the patient or next of kin, or review of hospital notes if they could not be contacted. Other secondary exploratory endpoints included: unplanned revascularisation, stroke or TIA, and hospitalisation for heart failure or arrhythmia.

The trial started screening patients on October 1st, 2016, but was halted early on March 1st, 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. By this time 6,696 patients had been screened, of whom 2,571 had consented and underwent randomisation, with a final 2,532 being included in the intention to treat analysis.

The trial had initially been powered to recruit 4,372 participants with 2,186 per arm based on 80 % statistical power to detect a 25 % reduction in the primary endpoint in the influenza group.

The mean age of participants was 60 years, 18.2 % were female and 35.5 % current smokers. Of note, 54.5 % were admitted with STEMI, 45.2 % with NSTEMI and 0.3 % with stable coronary artery disease, and 74.3 % were treated with PCI. The cross over-rate from the placebo to vaccine arm was 13.2 %.

What is the main result?

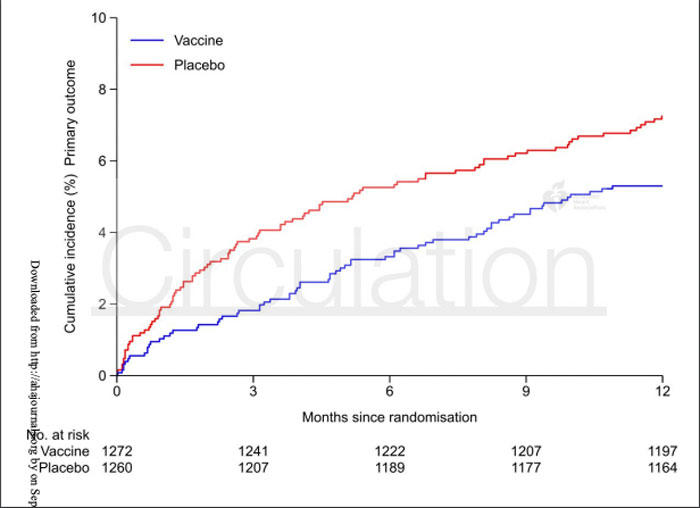

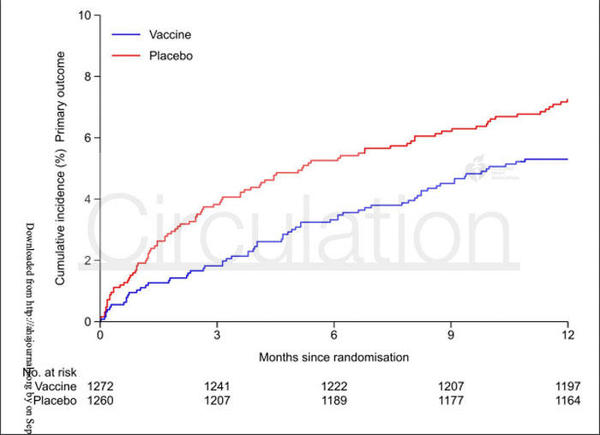

The primary endpoint, a composite of all-cause death, MI, or stent thrombosis, for influenza vaccine versus placebo was 5.3 % vs. 7.2 % (HR 0.72; 9 5% CI 0.52 to 0.99; p = 0.04).

With respect to secondary endpoints, the rates of all-cause death were 2.9 % vs. 4.9 % (p = 0.01), cardiovascular death were 2.7 % vs. 4.5 % (p = 0.014), MI were 2.0 % vs. 2.4 % (p = 0.57) and stent thrombosis 0.5 % vs. 0.2 % (p = 0.34).

Across all subgroups, calculated hazard ratios (95 % CI) were consistent with the primary composite endpoint result.

Serious adverse events were of similar type and incidence in the vaccine (n = 35) and placebo (n = 31) groups (2.75 % vs. 2.46 %).

Incidence of injection site reactions were reported significantly more frequently in participants receiving influenza vaccine (12.1 % vs. 6.5 %; p = 0.0001).

Source: Circulation

Critical reading and the relevance for clinical practice

The results of the IAMI trial indicate that among patients presenting with acute MI, influenza vaccination within 72-hours of PCI, or during index hospitalisation, resulted in a lower risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular death at 12-months when compared to placebo.

No inference can be drawn about the stable coronary cohort as only n = 8 (0.3 %) patients were recruited at the time of study termination.

These findings are consistent with previous studies, primarily the FLUVACS study5, which showed that the greatest positive effect of influenza vaccination is seen in the highest-risk subjects with acute-MI.

The trial was terminated early due to the COVID-19 pandemic and as result, the number of participants enrolled was less than originally intended based on sample size calculations. As well as this, the cross over rate in the placebo arm was 13.2 %. Considering both of these factors would tend to bias the results towards the null hypothesis, it makes the findings of the IAMI all the more impressive.

Time-to-event curves for the study separated early following injection and stabilised around 3-months, indicating that the therapeutic effect of the vaccine is in the early stages following acute-MI, which is characterised by high levels of inflammation.

The authors postulate that a number of mechanisms may be behind this, such as the prevention of acute influenza infection which can trigger cardiovascular events or that influenza vaccination in itself may exert an anti-inflammatory and plaque stabilising effect through the lowering of pro-inflammatory cytokines and upregulation of genes involved in interferon signalling8,9,10.

It is worth noting however that there was no reduction in the risk of MI between the two arms [n = 25 (2.0 %) vs 29 (2.4 %); p = 0.57], but there were less deaths due to MI in vaccinated participants [n = 5 (0.4 %) vs 12 (1.0 %)].

The risk of cardiovascular death was reduced among vaccinated participants [n = 34 (2.7 %) vs. 56 (4.5 %); p = 0.014], with the majority of cardiovascular deaths in both the vaccine and placebo groups being attributed to ‘presumed cardiovascular death’ [n = 22 (1.7) vs. 30 (2.4 %)].

Importantly, all deaths not clearly attributed to a non-cardiovascular cause were presumed cardiovascular deaths. Among the listed causes of cardiovascular deaths, the rates were similar for cerebrovascular event [n = 1 (0.2 %) vs. 2 (0.2 %)], heart failure or cardiogenic shock [n = 2 (0.2 %) vs. 2 (0.2 %)], sudden cardiac death [n = 3 (0.2) vs. 6 (0.5 %)].

In summary, the IAMI trial showed that influenza vaccination in the setting of acute-MI resulted in a lower risk of composite all-cause mortality and cardiovascular death. As well as this, they showed that administration of the influenza vaccine within 72-hours of PCI or hospitalisation for acute-MI is safe. This supports the use of influenza vaccination as part of routine, in-hospital care following acute-MI. This may have profound effects on the delivery of influenza vaccinations in the post AMI setting and may provide a significant reduction in cardiac morbidity and mortality associated with influenza.

References

- Frøbert O, Götberg M, Erlinge D, et al. Influenza Vaccination after Myocardial Infarction: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Multicenter Trial: IAMI trial. Circulation. 2021; Aug 30

- Collins SD. Excess mortality from causes other than influenza and pneumonia during influenza epidemic. Public Health Rep. 1932;47:2159–2179

- Ciszewski A, Bilinska ZT, Brydak LB, et al. Influenza vaccination in secondary prevention from coronary ischaemic events in coronary artery disease: FLUCAD study. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1350–1358.

- Phrommintikul A, Kuanprasert S, Wongcharoen W, et al. Influenza vaccination reduces cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1730–1735.

- Gurfinkel EP, de la Fuente RL, Mendiz O, Mautner B. Influenza vaccine pilot study in acute coronary syndromes and planned percutaneous coronary interventions: the FLU Vaccination Acute Coronary Syndromes (FLUVACS) Study. Circulation. 2002 May 7;105(18):2143-7.

- Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:407–477.

- Davis MM, Taubert K, Benin AL, et al. Influenza vaccination as secondary prevention for cardiovascular disease: a science advisory from the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol.2006;48:1498–1502.

- Kwong JC, Schwartz KL, Campitelli MA, Chung H, Crowcroft NS, Karnauchow T, Katz K, Ko DT, McGeer AJ, McNally D, et al. Acute Myocardial Infarction after Laboratory-Confirmed Influenza Vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378: 345-353.

- Atoui R, F FE, Sroka K, Mireau J, McElhaney JE, Hare G. Influenza Vaccination Blunts the Inflammatory Response in Patients Undergoing Cardiopulmonary Bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020

- Bermudez-Fajardo A, Oviedo-Orta E. Influenza vaccination promotes stable atherosclerotic plaques in apoE knockout mice. Atherosclerosis. 2011; 217: 97-105