30 Sep 2021

Percutaneous myocardial revascularization in late-presenting patients with STEMI

Selected in Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC) by A. Cader , S. R. Khan

Through this registry-based analysis, the authors sought to assess short and long-term outcomes of revascularisation in a latecomer STEMI population presenting between 12 to 48 hours of symptom onset.

References

Authors

Frédéric Bouisset, Edouard Gerbaud, Vincent Bataille, Pierre Coste, Etienne Puymirat, Loic Belle, Clément Delmas, Guillaume Cayla, Pascal Motreff, Gilles Lemesle, Nadia Aissaoui, Didier Blanchard, François Schiele, Tabassome Simon, Nicolas Danchin, Jean Ferrières, and on behalf of the FAST-MI Investigators

Reference

J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021 Sep, 78 (13) 1291–1305

Published

September 2021

Link

Read the abstractReviewers

Our Comment

Why this study? – the rationale/objective

Despite its gradually decreasing prevalence in recent times, late-presenters constitute 10 to 15 % of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients1,2. Late-presenters are those that present > 12 hours after symptom onset, a time limit that has been derived exclusively from studies in the thrombolysis era.

There remains some controversy regarding the benefit of PCI in the 12 to 48-hour window following STEMI symptom onset, especially in the absence of on-going ichaemia, with some discordance in trans-Atlantic guideline recommendations3,4.

Through this registry-based analysis, the authors sought to assess short and long-term outcomes of revascularisation in such a latecomer STEMI population presenting between 12 to 48 hours of symptom onset5.

How was it executed? - the methodology

In this observational registry-based study, the investigators analyzed STEMI patients derived from the FAST-MI (French Registry of Acute ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction) nationwide French registry, which contained all-comer acute myocardial infarctions over 1-month periods in 2005, 2010, and 2015.

The late-comer STEMI cohort was further analyzed after excluding those that received fibrinolysis (n = 59) and were deceased within 48 hours (n = 32). These late-comers were compared after allocation into two groups: Revascularised group (either by PCI or CABG within 12-48 hours) and non-revascularised group.

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes included recurrent acute MI, stroke, and TIMI [Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction] bleeding.

What is the main result?

Among the total 6,273 STEMI patients, 1,169 (18.6 %) were late-comers. After excluding those treated with fibrinolytics and deceased within 2 days, the remaining 1,077 late-comer STEMIs were divided into two groups: 729 (67.7 %) of whom were revascularised within 48 hours of hospital admission, versus 348 who were not. The majority (726/729) of the revascularised underwent PCI, while 3 underwent CABG.

Comparison of early-comers vs late-comers

Age, diabetes, atypical chest pain, and prior heart failure were independently associated with late presentation on multivariate analysis. Interestingly, female sex was not associated with late STEMI presentation.

Late-comers were less likely to undergo coronary angiography (91.9 % vs 96.5 %; P < 0.001), and consequently, PCI (76.8 % vs 86.5 %; P < 0.001), with less frequent incidence of post-PCI TIMI flow grade 2/3 (80.4 % vs 88.5 %; p < 0.001).

Comparison of revascularised vs non-revascularised late-comers

Revascularised late-comer patients were younger, less likely to be hypertensive or have co-morbidities, and more likely to be smokers and present with a family history of coronary artery disease. Revascularised late-comers received invasive treatment with an approximately 4-hour delay than early comers (Median door-to-balloon time 5.4 vs 1.4 hours, p < 0.001).

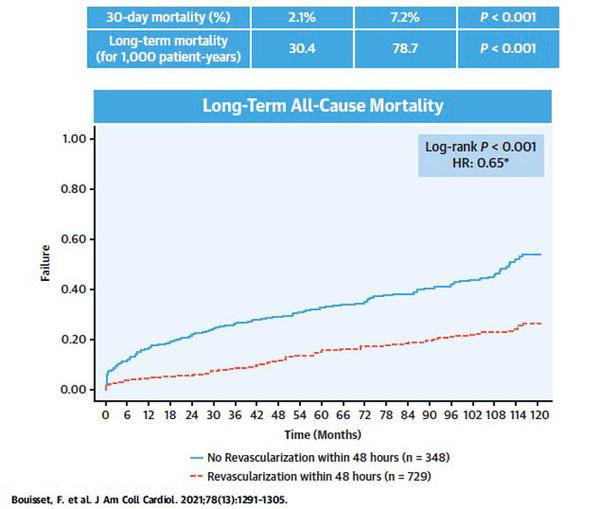

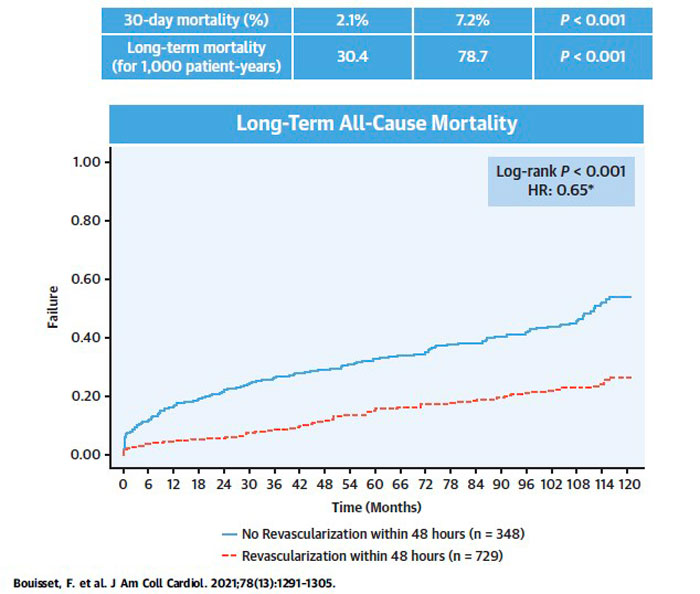

At 30-day follow-up, all-cause mortality was significantly lower in the revascularised late-comer population compared with those not revascularised (2.1 % vs 7.2 %; p < 0.001). Long-term mortality after a median follow-up of 58 months was also significantly lower in the revascularised group (30.4 per 1,000 patient-years [95 % CI 25.7 -35.9] vs 78.7 per 1,000 patient-years [95 % CI 67.2 – 92.3]; p < 0.001). Recurrent MI was also significantly less in the revascularised group on long-term follow-up. TIMI major bleeding was more frequent among non-revascularised late-comers at 30-day follow-up (0.4 % vs 2.0 %; p = 0.016).

On multivariate analysis, revascularisation of latecomer STEMI patients was independently associated with a significant 35 % reduction of mortality (Hazard Ratio 0.65; 95 % CI 0.50 – 0.84; p = 0.001). The propensity score matching analysis (267 pairs) also favoured revascularisation within 12-48 hours (log-rank test p = 0.006).

Source: JACC

Critical reading and the relevance for clinical practice

This study by Bouisset, et al., albeit limited by its non-randomized observational design, is the first large registry to report prognostic benefits of better long-term clinical outcomes of PCI in late-comer STEMI patients 12-48 hours after symptom onset. Although the authors circumvented the immortal time bias by excluding those deceased within 48 hours of admission, elements of bias remain in the baseline population in terms of a more favourable profile in the revascularised group, who also had significantly less chronic kidney disease, less prior heart failure, a lower incidence of Killip Class > 2, lower GRACE risk score and a better ejection fraction.

The benefit of revascularisation of late-comer STEMI patients beyond the 12-hour window remains a matter of debate. Both the ESC and ACC/ AHA guidelines stipulate a Class I recommendation for PCI beyond 12 hours in the presence of haemodynamic instability (i.e. cardiogenic shock)3,4 or acute heart failure4, irrespective of time delay from hospital presentation3. As for a routine primary PCI strategy in the absence of ongoing pain or dynamic ECG changes, the ESC guidelines give a Class IIa recommendation for PCI in late STEMI within 12-48 hours of symptom onset4. The American guidelines have a Class IIa recommendation for PCI, in presence of evidence of ongoing ischemia, with the time window reduced to 12 to 24 hours after symptom onset3.

The late STEMI population in this study comprised of a combination of all-comers with heterogeneity in haemodynamic stability, ongoing ischaemia, and the presence/ absence of typical chest pain, factors that are considered in decision-making in terms of stretching the time window of late PCI, given that the benefit of PCI in some subsets will be greater than for others. While the authors addressed this to an extent with propensity score matching still favouring PCI in late-comers, the benefits of late PCI in specific subsets of populations, particularly those with no on-going chest pain remain a matter of contention.

The 12-hour window for revascularisation in STEMI is a time limit that has been derived from studies in the thrombolysis era6-8. It Is important to reiterate that this current debate of revascularizing late-comer STEMIs is focused on PCI, not fibrinolysis. Further, this narrow cut-off is based on the assumption that the infarct-related artery (IRA) remains permanently closed prior to revascularisation, resulting in irreversible myocardial loss. In the recently reported Korean STEMI registry, there were no significant differences of pre-procedural TIMI 1-3 flow between early and late presenters (35.5 % vs. 35.4 % respectively)2.

In the BRAVE-2 trial, TIMI flow grade ≥ 2 was seen in as many as 43.4 % of asymptomatic late STEMI patients randomised to PCI, while 29 % of them had collateral flow9. A significantly reduced final left ventricular infarct size was seen in the invasive group on single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)9. Albeit underpowered, the trial also demonstrated prognostic benefits of PCI in late-comers with reduced 4-year mortality10.

The potential for myocardial salvage by late revascularisation is central to this debate on timing. Preserved blood flow in the IRA has been shown to be associated with smaller infarct size and better recovery of EF11. Furthermore, presence of some degree of viable myocardium in late STEMI presenters up to 72 hours has been demonstrated by both magnetic resonance imaging12 and SPECT13 and studies, even when the IRA is occluded13. Thus, while myocardial salvage is less with late presenters than early presenters, substantial myocardial salvage may be achieved by performing PCI in the 12-48 hour time window of late STEMI presenters, translating to better outcomes, as observed in this study5. The results of this study are especially pertinent in the context of COVID-19 pandemic and for those in lower-middle-income countries, where the burden of late-comer STEMIs still remains relatively high.

Finally, while there might still be debate on how long to extend the time period of late STEMI PCI, there is no doubt that the early reperfusion of STEMI results in superior clinical outcomes14. Much of this benefit hinges on the early presentation of patients to the hospital, as well as the rapid delivery of care after presentation to the hospital. Interestingly also, the door to balloon time was not as fast for revascularized late comers in FAST MI, as they were for the early comers (5.4 vs 1.4 hours). Additionally, the reduction in prevalence of late STEMI in the FAST-MI registry from 23.6 % in 2005 to 16.1 % in 2015 has been attributed to increased public awareness through targeted campaigns, one that can be replicated to improve systems of STEMI care elsewhere in the world as well.

References

- Roberto M, Radovanovic D, de Benedetti E, et al. Temporal trends in latecomer STEMI patients: insights from the AMIS Plus registry 1997- 2017. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2020;73:741–748.

- Cho KH, Han X, Ahn JH, et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with late presentation of STsegment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:1859–1870.

- O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of STelevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/ American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 013;61:e78–e140.

- Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the Task Force for the Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Patients Presenting With ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119–177.

- Bouisset F, Gerbaud E, Bataille V, et al; FAST-MI Investigators. Percutaneous Myocardial Revascularization in Late-Presenting Patients With STEMI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78(13):1291-1305

- Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Streptochinasi nell’Infarto Miocardico (GISSI). Effectiveness of intravenous thrombolytic treatment in acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1986;1:397–402.

- ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither among 17,187 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-2. Lancet. 1988;2:349–360.

- EMERAS (Estudio Multicentrico Estreptoquinasa Republicas de America Del Sur) Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of late thrombolysis in patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction.Lancet. 1993;342:767–772.

- Schomig A, Mehilli J, Antoniucci D, et al. Mechanical reperfusion in patients with acute myocardial infarction presenting more than 12 hours from symptom onset: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:2865–2872.

- Ndrepepa G, Kastrati A, Mehilli J, Antoniucci D, Schomig A. Mechanical reperfusion and long-term mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction presenting 12 to 48 hours from onset of symptoms. JAMA. 2009;301:487–488.

- Ndrepepa G, Kastrati A, Schwaiger M, et al. Relationship between residual blood flow in the infarct-related artery and scintigraphic infarct size, myocardial salvage, and functional recovery in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1782–1788

- Nepper-Christensen L, Lonborg J, Hofsten DE, et al. Benefit from reperfusion with primary percutaneous coronary intervention beyond 12 hours of symptom duration in patients with ST segment-elevation myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:e006842.

- Busk M, Kaltoft A, Nielsen SS, et al. Infarct size and myocardial salvage after primary angioplasty in patients presenting with symptoms for <12 h vs.12-72 h. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1322–1330.

- Brodie BR, Stone GW, Cox DA, et al. Impact of treatment delays on outcomes of primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction: analysis from the CADILLAC trial. Am Heart J. 2006;151:1231–1238.

1 comment

Hello Iask about benifet of Revascularization of RCA in late comer more than 48hs with bradycardia