ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction following transcatheter aortic valve replacement

Selected in JACC by E. Asher

The aim of the current study was to determine the clinical characteristics, management and outcomes of STEMI after TAVR.

References

Authors

Laurent Faroux, Thibault Lhermusier , Flavien Vincent, Luis Nombela-Franco, Didier Tchétché, Marco Barbanti, Mohamed Abdel-Wahab, Stephan Windecker, Vincent Auffret, Diego Carter Campanha-Borges, Quentin Fischer, Erika Muñoz-Garcia, Ramiro Trillo-Nouche, Troels Jorgensen, Vicens Serra, Stefan Toggweiler, Giuseppe Tarantini, Francesco Saia, Eric Durand, Pierre Donaint, Enrique Gutierrez-Ibanes, Harindra C Wijeysundera, Gabriela Veiga, Giuseppe Patti, Fabrizio D'Ascenzo, Raul Moreno, Christian Hengstenberg, Chekrallah Chamandi, Lluis Asmarats, Rosana Hernandez-Antolin, Joan Antoni Gomez-Hospital, Juan Gabriel Cordoba-Soriano, Uri Landes, Victor Alfonso Jimenez-Diaz, Ignacio Cruz-Gonzalez, Mohammed Nejjari, François Roubille, Éric Van Belle, German Armijo, Saifullah Siddiqui, Giuliano Costa, Sameh Elsaify, Thomas Pilgrim, Hervé le Breton, Marina Urena, Antonio Jesus Muñoz-Garcia, Lars Sondergaard, Montserrat Bach-Oller, Chiara Fraccaro, Hélène Eltchaninoff, Damien Metz, Maria Tamargo, Victor Fradejas-Sastre, Andrea Rognoni, Francesco Bruno, Georg Goliasch, Marcelo Santaló-Corcoy, Jesus Jimenez-Mazuecos, John G Webb, Guillem Muntané-Carol, Jean-Michal Paradis, Antonio Mangieri, Henrique Barbosa Ribeiro, Francisco Campelo-Parada, Josep Rodés-Cabau

Reference

10.1016/j.jacc.2021.03.014

Published

May 2021

Link

Read the abstractReviewer

My Comment

Why this study? – the rationale/objective

Almost 50 % of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) patients exhibit some degree of coronary artery disease (CAD). ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) rate is low among patients post-TAVR (1 % to 8 % of all post-TAVR ACS). Nevertheless, they are at increased risk of death and major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular event (MACCE). The poor prognosis of post-TAVR STEMI could be related to patients’ characteristics, as well as impaired coronary flow, leaflet thrombosis, coronary embolism, late valve migration. More importantly, the potential interaction between the transcatheter heart valve and the coronary ostia

may be associated with a significant delay or even preclude primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

The aim of the current study was to determine the clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes of STEMI after TAVR.

How was it executed? – the methodology

A multicenter study including 118 patients presenting with STEMI at a median of 255 days (IQR: 9 to 680 days) after TAVR.

Procedural features of STEMI after TAVR managed with primary PCI were compared with all-comer STEMI: 439 non-TAVR patients who had primary PCI within the 2 weeks before and after each post-TAVR STEMI case in 5 participating centers from different countries.

PCI failure was defined as:

- a final diameter stenosis > 30 %

- or a post-dilation thrombosis in myocardial infarction flow grade 0 or 1.

Post-STEMI clinical outcomes were recorded and included all-cause death, MI, and stroke. MACCEs were defined as death, MI, or stroke.

What is the main result?

- Compared with the control group, TAVR patients were older (80.7 ± 7.6 years vs. 64.1 ± 12.7 years; p < 0.001) and exhibited a much higher burden of comorbidities, with higher rates of diabetes mellitus (31.4 % vs. 16.6 %; p < 0.001), hypertension (83.3 % vs. 50.8 %; p < 0.001), prior CAD (69.6 % vs. 12.5 %; p < 0.001).

- The rate of coronary angiography performed via the femoral access was much higher in patients with prior TAVR (47.1 % vs. 9.6 %; p < 0.001).

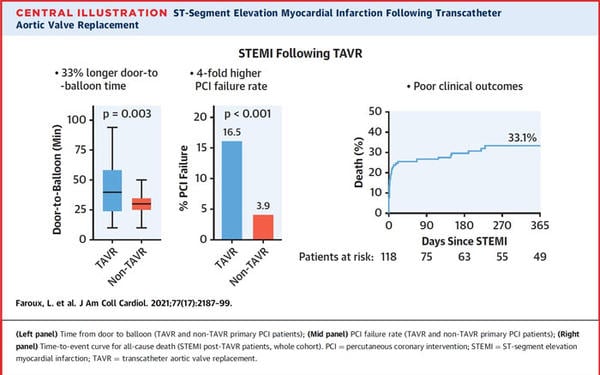

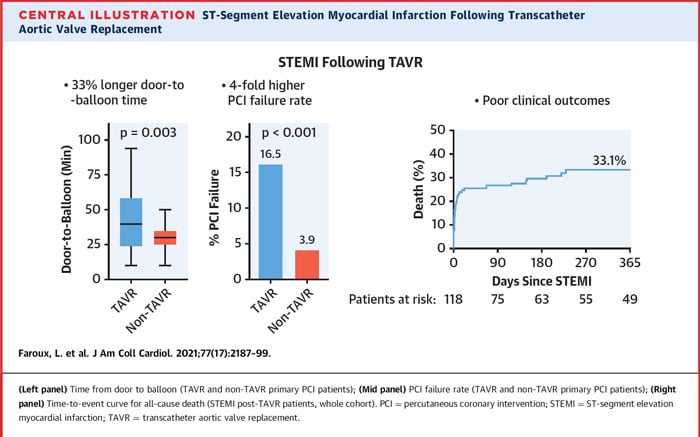

- Median door-to-balloon time was higher in TAVR patients (40 min [IQR: 25 to 57 min] vs. 30 min [IQR: 25 to 35 min]; p = 0.003).

- Procedural time, fluoroscopy time, dose-area product, and contrast volume were also higher in TAVR patients (p < 0.01 for all).

- PCI failure occurred more frequently in patients with previous TAVR (16.5 % vs. 3.9 %; p < 0.001).

- PCI failure in the post-TAVR patients occurred in:

- 5 patients - ostia cannulation failure.

- 4 patients - failure to cross the lesion with the guidewire.

- 3 patients – no reflow phenomena.

- 1 patient – coronary perforation with cardiac tamponade

- 1 patient – died during the procedure before PCI completion.

- Both in-hospital and late outcomes were poorer in patients with post-TAVR STEMI, with an increased incidence of death (p < 0.001), stroke (p = 0.008), and MACCE (p < 0.001).

- By multivariable analysis, estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 ml/min (hazard ratio [HR]: 3.02; 95 % CI: 1.42 to 6.43; p = 0.004), Killip class ≥ 2 (HR: 2.74; 95 % CI: 1.37 to 5.49; p =0.004), and PCI failure (HR: 3.23; 95 % CI: 1.42 to 7.31; p = 0.005) determined a higher risk of death.

Source: JACC

Critical reading and the relevance for clinical practice:

The main findings of the study are:

- about one-third of STEMI events after TAVR occurred within the few months following the procedure, and a non-atherothrombotic mechanism (coronary embolism, late prosthesis migration) was involved in ~ 15 % of cases.

- about 85 % of patients were managed with primary PCI.

- in primary PCI patients, prior TAVR was associated with a longer door-to-balloon time and a much higher PCI failure rate, partially due to coronary access issues specific to the TAVR population.

- in-hospital and late outcomes following post-TAVR STEMI were poor (in-hospital and 1-year mortality rates up to 25 % and 33 %, respectively), with PCI failure determining an increased risk.

Of note, patients presenting STEMI after TAVR were frequently in an unstable clinical condition at admission, with 47 %, 18 %, and 11 % of the study population presenting congestive signs, cardiogenic shock, and cardiac arrest, respectively. Moreover, lesion complexity was similar between patients with and without prior TAVR. This supports the hypothesis that the increased revascularization time and the higher proportion of failed PCI in TAVR patients were not related to lesion complexity discrepancies, but rather to an extrinsic factor.

Should common practice and guidelines be changed?

The study had several limitations: first, the study was performed in intermediate- to high-risk patients, and the findings may not apply to lower-risk populations with TAVR. Second, coronary embolism was found to be responsible for STEMI in a significant proportion of patients post-TAVR.

What is your approach regarding patients with post-TAVR STEMI?

Do you think that patients with post-TAVR STEMI should or should not be directed to and treat in centers with no TAVR experience?

This might highlight the importance of establishing clear recommendations and standardized practices in this setting.

No comments yet!