16 May 2023

30 years of primary PCI – a tale of perseverance

Over the last 30 years, primary PCI (pPCI) has evolved from an experimental ‘rescue’ intervention to an essential routine procedure – performed daily in cathlabs around the world – which is responsible for saving millions of lives. However, its path to success was far from smooth.

Geoffrey O. Hartzler

The pPCI journey began in the early 1980s when Geoffrey O. Hartzler, from the Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, first had the foresight to use percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty to treat AMI, publishing his experiences in 41 patients in 1983.1

Based on his knowledge of pathophysiology and visionary mind, William C. Roberts (a pathologist and Editor in Chief of the American Journal of Cardiology) endorsed Hartzler’s findings in a letter published in 1984,2 challenging current dogma, but the medical community was far from convinced.

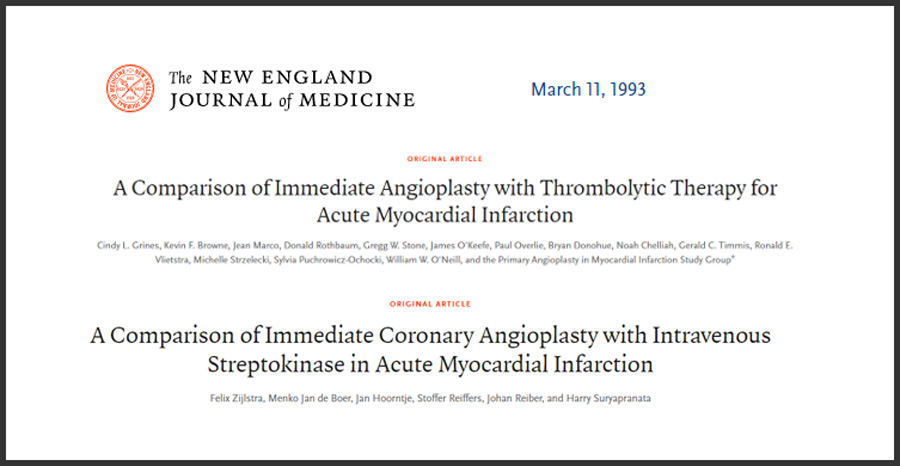

Using a mechanical treatment to open acutely occluded vessels was thought highly controversial by most of the cardiology community at the time, given that new thrombolytic therapies were emerging. Proponents were called ‘savages’ and ‘cowboys’ for considering primary angioplasty over newly developed drugs. The lack of support meant it was difficult to find funding for further investigations and it took another 10 years before Hartzler’s first experimental findings were confirmed in randomised trials. In March 1993 – 30 years ago this year – the first two randomised trials demonstrating that primary angioplasty was superior to thrombolysis were published: one by the Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction (PAMI) Study Group, which included among others, Cindy L. Grines, Jean Marco and William W. O’Neill,3 and one by Felix Zijlstra and the group at Zwolle, the Netherlands.4

“When I was a cardiology fellow, we were allowed to perform angioplasty in patients with an MI only after thrombolytics. This meant that correction of arterial occlusion could be delayed by over an hour.

We suggested that simultaneously combining the two methods of treatment, or eliminating thrombolytic therapy altogether, could improve patient outcomes and conducted a series of studies to investigate this. Our findings were met with a great deal of hostility and criticism and, even after additional studies confirmed our results, the role of primary angioplasty continued to be questioned for many years. It is gratifying to note that pPCI is now the standard-of-care treatment for STEMI around the world.”

Cindy Grines as a fellow, with Eric Topol

In December 1993, Hartzler and team published experiences with primary angioplasty in 1,000 consecutive unselected high-risk patients with AMI.5 Despite the growing evidence, there remained much scepticism; however, robust clinical work continued to confirm the value of primary angioplasty and, in 1997, a meta-analysis of the first 10 international trials highlighted its associated significant 34% reduction in 30-day mortality: 6.5% with thrombolysis versus 4.4% with primary angioplasty (odds ratio 0.66; 95% CI 0.46–0.94; p=0.02).6

Following this initial demonstration of safety and efficacy, the scarce availability of pPCI became apparent, which raised a new major concern about its applicability. However, this barrier was overcome by pioneering centres providing 24-hour pPCI services despite the absence of cardiac surgery on site.7,8 Nevertheless, primary angioplasty was still underused as it was offered only to the limited number of patients admitted directly to hospitals with interventional services spontaneously organised to work around the clock. Transportation from the local hospital to an angioplasty centre was considered to represent a further major limitation to the widespread use of primary angioplasty, until trials such as PRAGUE, DANAMI-2 and AIR-PAMI in the early 2000s demonstrated that timely transfer to the cathlab was superior to onsite thrombolysis.9-11

“Our idea to transport these patients to a tertiary centre for pPCI, over a distance of up to 100 km, was initially met with furious criticism. We conducted the PRAGUE study9 without any financial support – thanks to the enormous enthusiasm of a young generation of cardiologists, nurses and other healthcare professionals who deeply believed in what they did for the patients. Positive results from our trials and others led to a major change in the organisation of acute cardiac care and the initiation of the first real model of hub-and-spoke network in cardiology.

This new approach decreased mortality not only because pPCI is more effective than thrombolysis, but also due to the fact that a much higher proportion of patients are treated with reperfusion treatment overall.”

Taken together, data from pivotal trials culminated in pPCI gaining a class I recommendation in ESC guidelines for STEMI in 2003.12 Focus then shifted to how to bring successful pPCI to as many people with STEMI as possible. A European survey, conducted in 2008, highlighted disparities in the use of pPCI.13 The study found that pPCI was the dominant reperfusion strategy in 16 countries, while thrombolysis was still widely used in 8 countries in Europe. Depending on the country, the use of pPCI varied widely from 5% to 92% of all STEMI patients, while the number of pPCIs per million inhabitants/year ranged from 20 to 970.

The leadership of EuroPCR and EAPCI seized the opportunity to improve STEMI care and launched the Stent for Life initiative in 2009. Stent for Life encouraged equal access to pPCI by citing guideline implementation barriers and outlining plans for the individual needs of different countries. After just 2–3 years, a new survey showed some positive changes, with the dominant reperfusion strategy noted as pPCI in 33 countries and thrombolysis in 4 European countries.14 Access to pPCI was still regarded as suboptimal in Europe and beyond, and to address further challenges, Stent for Life underwent global expansion and became Stent – Save a Life! in 2017, expanding the initiative to extra-European geographies. Today, its mission to improve delivery of life-saving pPCI continues.

“Today’s generation of interventional cardiologists may not view pPCI as ‘cutting edge’, but the development of pPCI represents a story of passion, dedication and courage. We must not forget that around a fifth of patients died early after STEMI in the pre-reperfusion era, but now, mortality is less than 3%. This commonplace cost-effective procedure has saved countless lives over the last 30 years.

What in the beginning seemed to be a ‘whim of spoiled young interventionalists’ became, in less than 10 years, the most important cardiovascular interventional procedure and now, the main mission of any interventional cardiologist.”

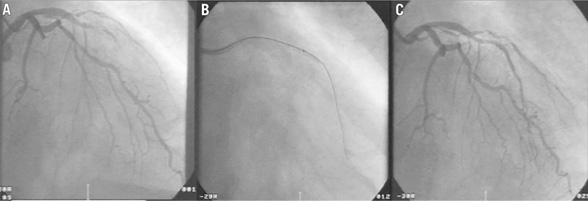

Despite the tremendous clinical impact of a treatment that completely changed the organisation of cardiology departments worldwide, little difference has been seen in the global concept of the procedure since its origin in 1993 (Figure 1).

pPCI has evolved from the simple inflation of balloons through 8Fr guiding catheters inserted in the femoral artery followed by days of anticoagulation, to the use of radial access, simple oral drug administration, routine stent implantation, ideally intravascular imaging assessment, and early discharge. However, the procedure remains substantially the same, with timely and expert organisation of the emergency team still the central pillar of success.15

Primary PCI procedure performed in March 1993:

A) Right anterior oblique angiographic image showing a thrombotic, acute, total occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery causing a large anterior STEMI;

B) Balloon dilatation (3.0x20mm) at the site of the occlusion;

C) Recanalised vessel after balloon angioplasty.15

The Stent – save a life! global initiative

Its mission: “To improve the delivery of care and patient access to the life-saving indication of pPCI, thereby reducing mortality and morbidity in patients suffering from AMI.”

Read more about the work of Stent – Save a Life!

References

- Hartzler GO, et al. Am Heart J. 1983;106:965–973.

- Roberts WC. Am J Cardiol. 1984;53:1410.

- Grines CL, et al. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:673–679.

- Zijlstra F, et al. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:680–684.

- O’Keefe JH, et al. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72:107G–115G.

- Weaver WD, et al. JAMA. 1997;278:2093–2098.

- Dellavalle A, et al. Coron Artery Dis. 1995;6:513–520.

- Wharton TP, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1943–1950.

- Widimský P, et al. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:823–831.

- Andersen HR, et al. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:733–742.

- Grines CL, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39:1713–1719.

- Van de Werf F, et al. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:28–66.

- Widimský P, et al. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:943–957.

- Kristensen SD, et al. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1957–1970.

- Ribichini F, Cuisset T. EuroIntervention. 2014;10:T7–T8.