"My Take on OCT Trials" by Davide Capodanno: CRT 2024

Where this strategy stands in the current landscape of options for PCI guidance

View a series of commented slides illustrating major takeaways from a network meta-analysis of Coronary Angiography, Intravascular Ultrasound, and Optical Coherence Tomography in the Guidance of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. These slides and comments were originally shared via Twitter upon the occasion of the 2024 Cardiovascular Research Technologies (#CRT2024) Educational Forum in Washington.

Browse through these slides to find an analysis of recent OCT Trials.

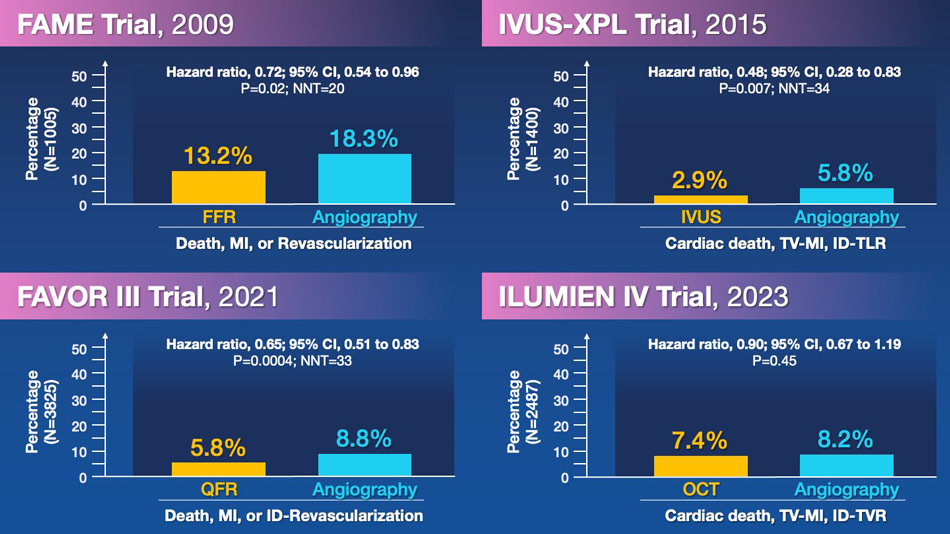

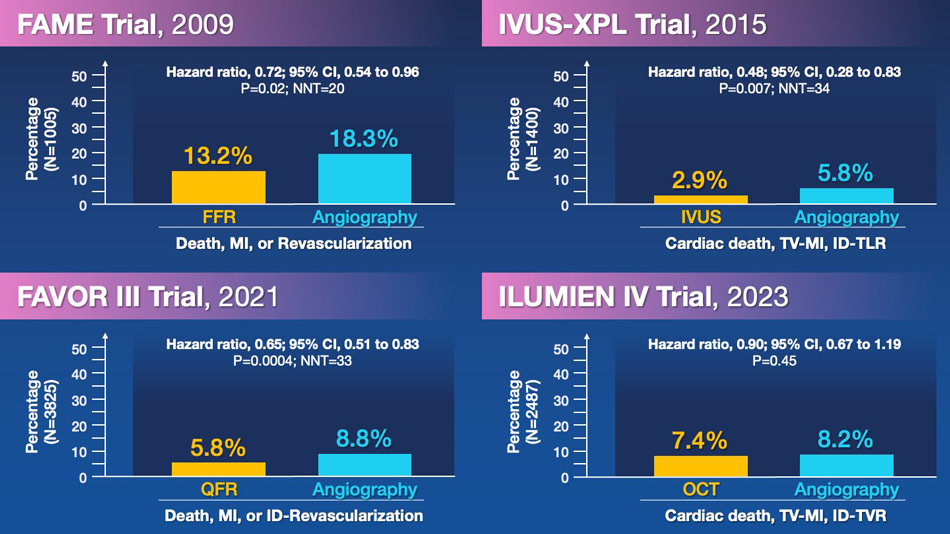

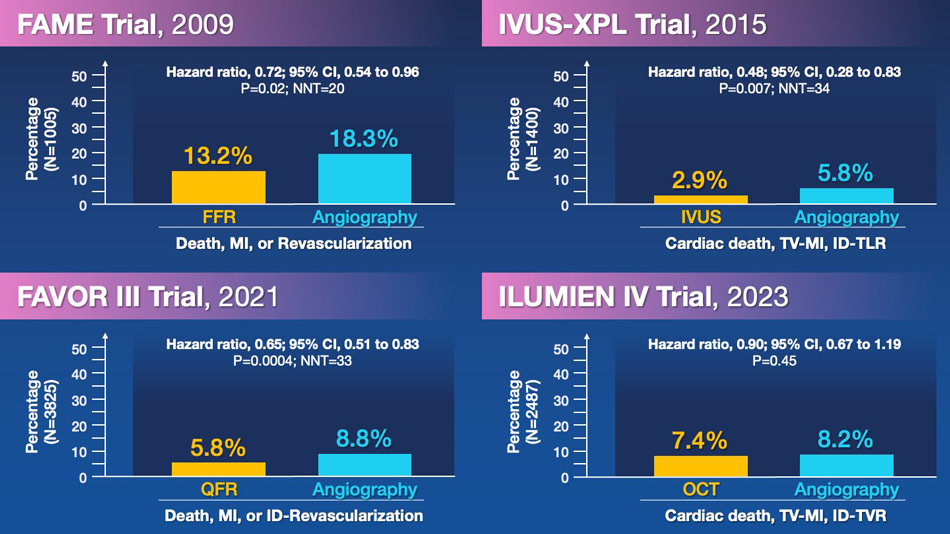

From a historical perspective, four landmark trials have assessed strategies for functional or imaging guidance in PCI. FAME, IVUS-XPL, and FAVOR III established roles for FFR, IVUS, and QFR in 2009, 2015, and 2021, respectively, with a number needed to treat to avoid a cardiovascular event ranging between 20 and 34. However, in 2023, OCT in ILUMIEN IV missed its opportunity to do the same.

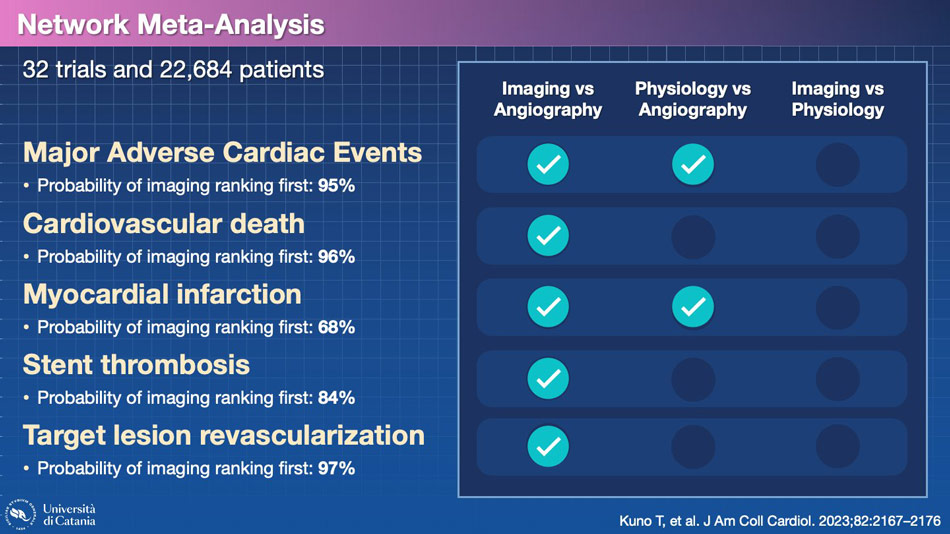

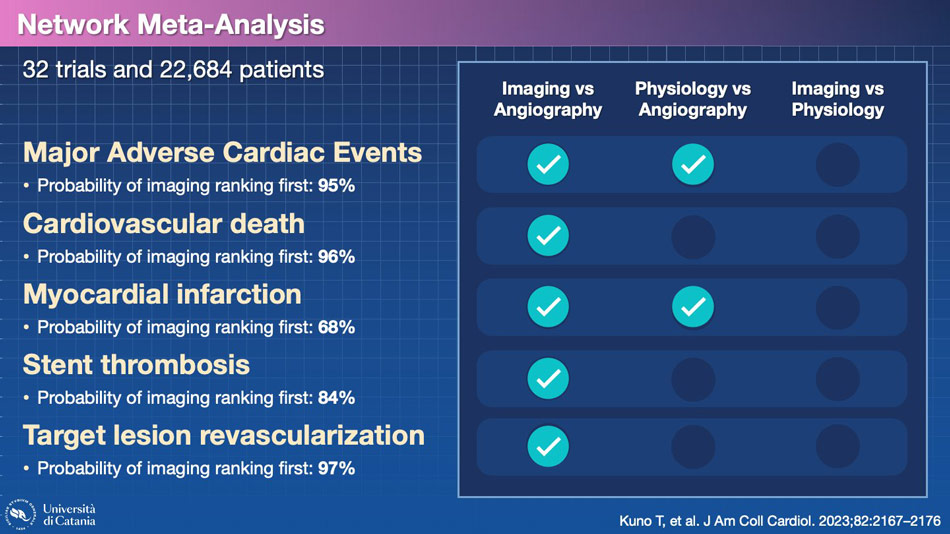

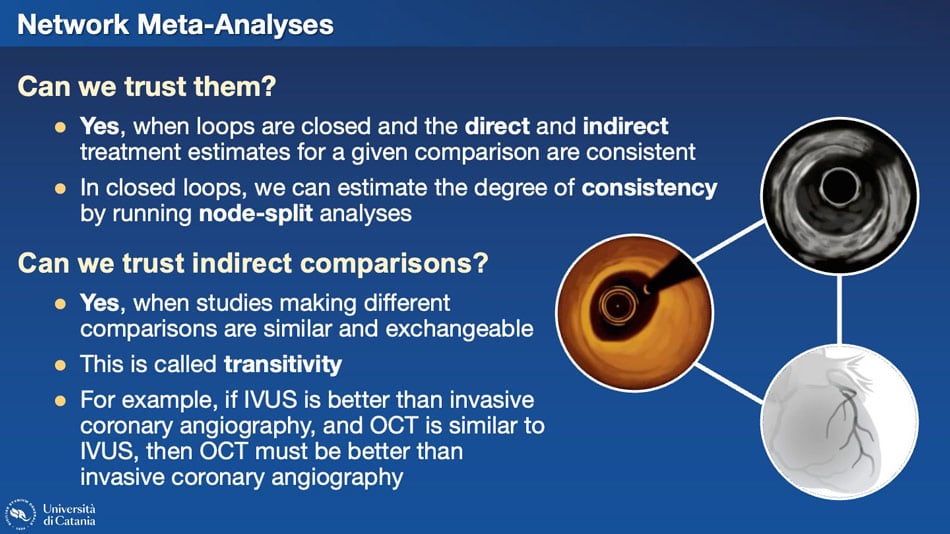

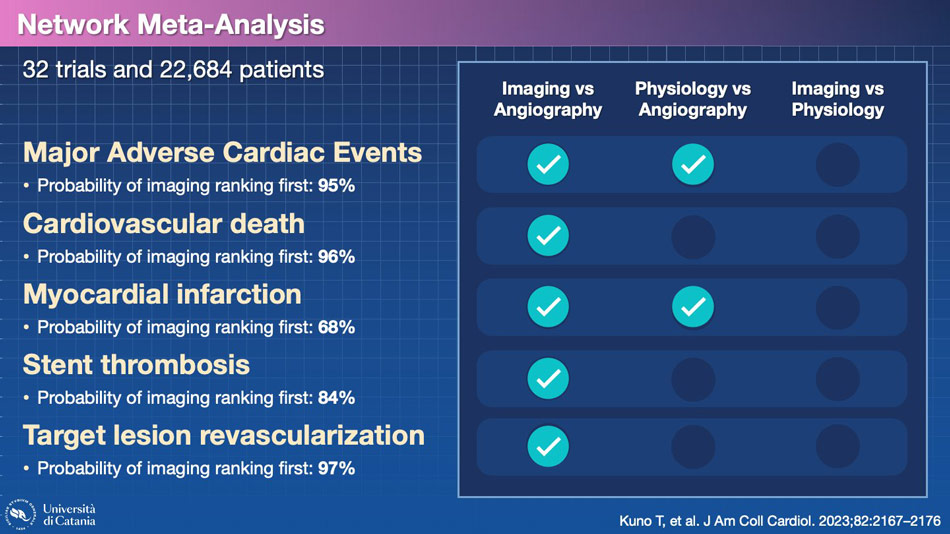

Given the numerous conducted trials and potential comparisons, there is an obvious temptation to conduct network meta-analyses. This study indicates that the probability of imaging ranking first, when compared with physiology and angiography, is higher for several clinical endpoints. Can we trust this result?

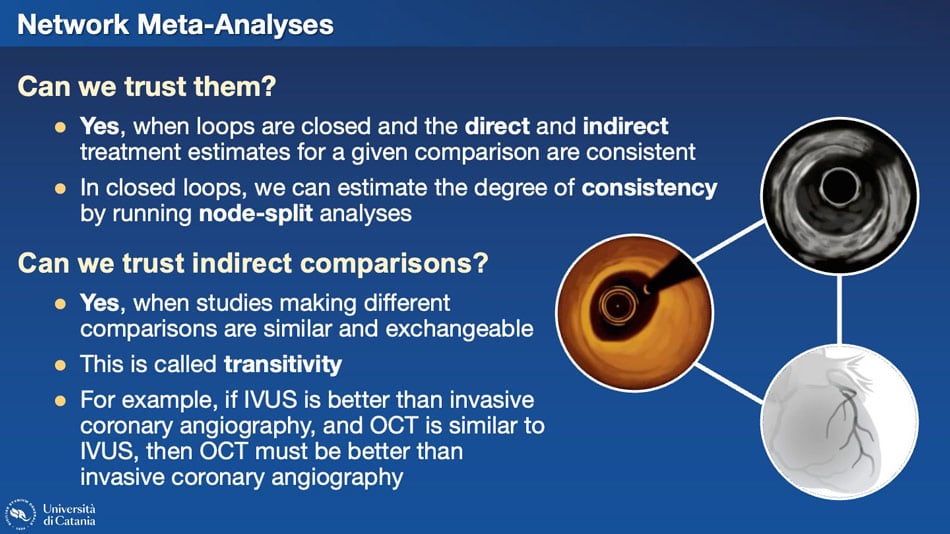

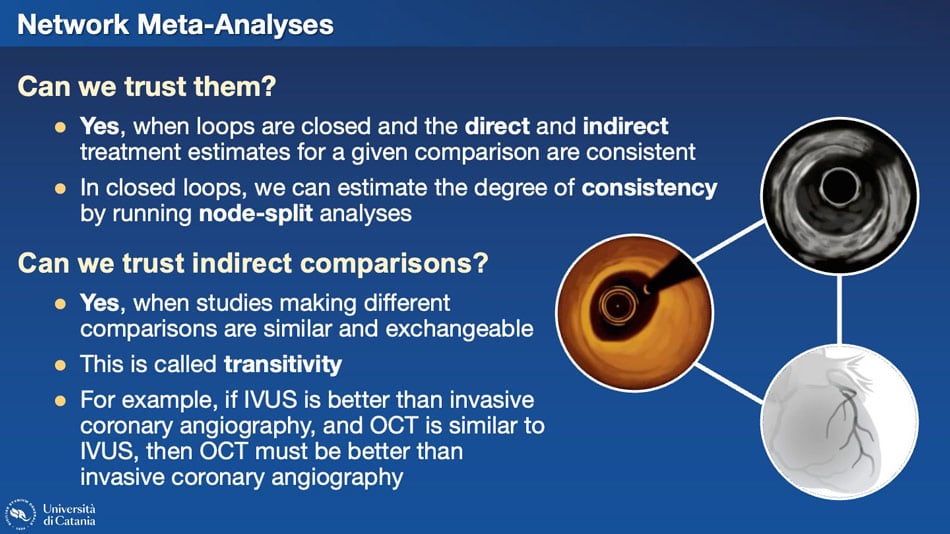

Several questions arise regarding network meta-analyses and their trustworthiness. In imaging, we have an interesting situation where a closed loop connects OCT, IVUS, and angiography, given all potential comparisons existing in the literature. When such closed loops exist, both direct and indirect comparisons can be considered. Reliable results hinge on the consistency between direct and indirect comparisons. If inconsistencies arise, relying on indirect evidence may lead to incorrect conclusions. Particularly, the transitivity assumption must be met. For example, if IVUS is superior to invasive coronary angiography, and OCT is similar to IVUS, then OCT must be superior to invasive coronary angiography. Is that the case?

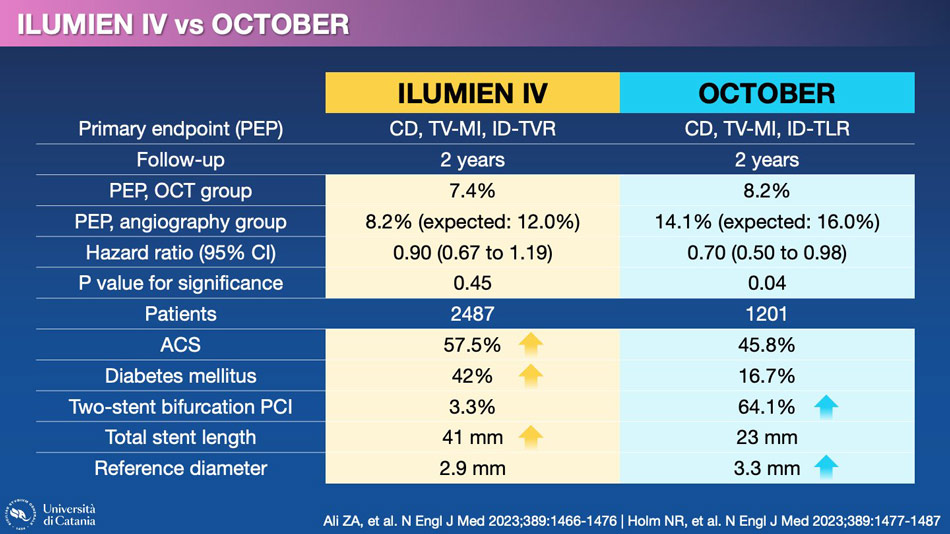

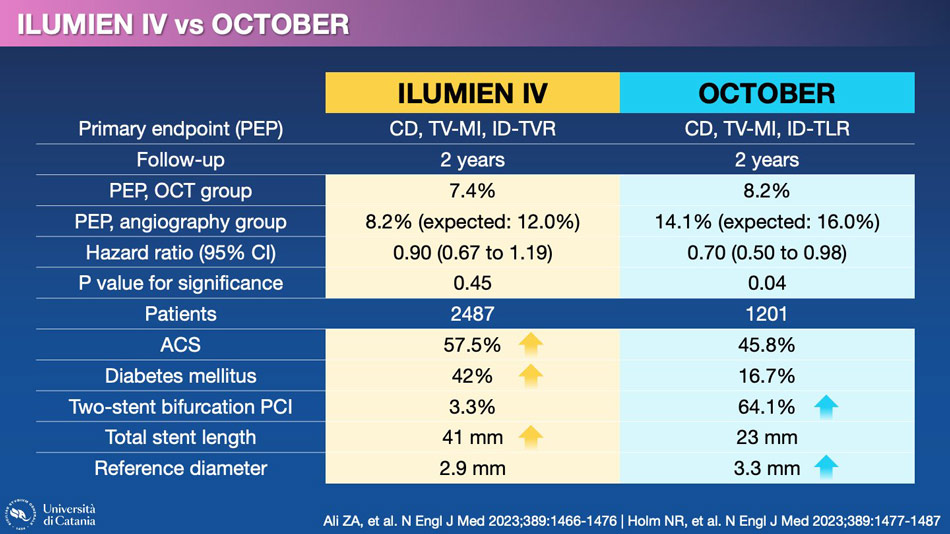

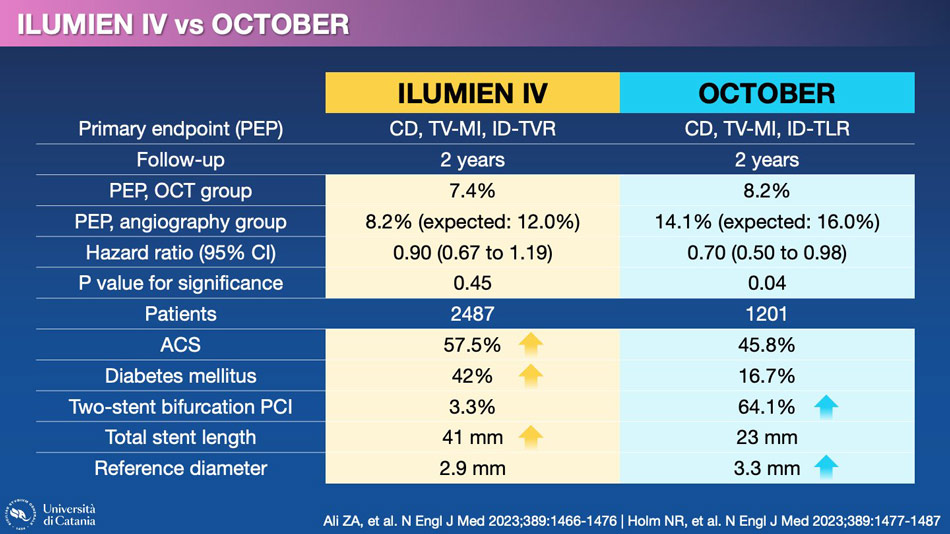

Let's take a look at the trials that have compared OCT with angiography. The two main trials, ILUMIEN IV and OCTOBER, yielded different results. This is not surprising considering the numerous differences in patient characteristics and the type of coronary lesions that were treated.

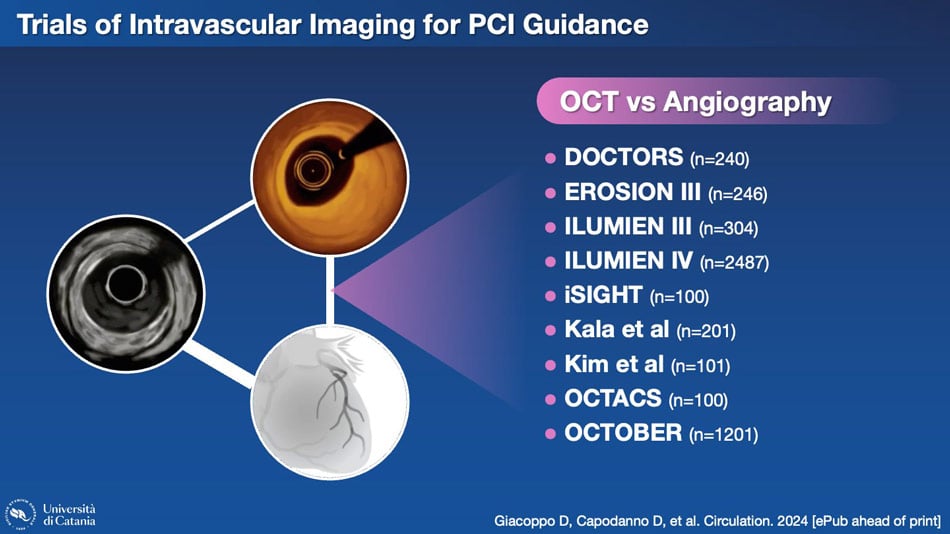

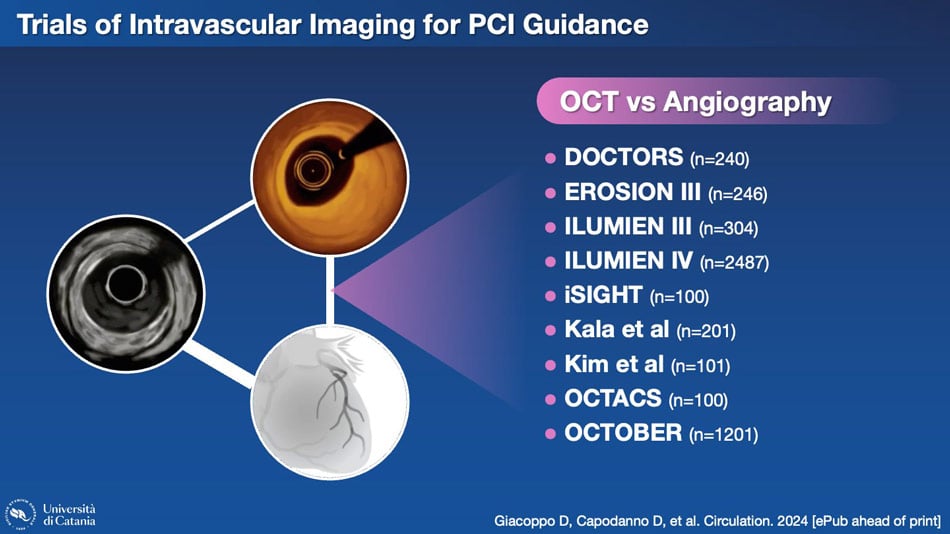

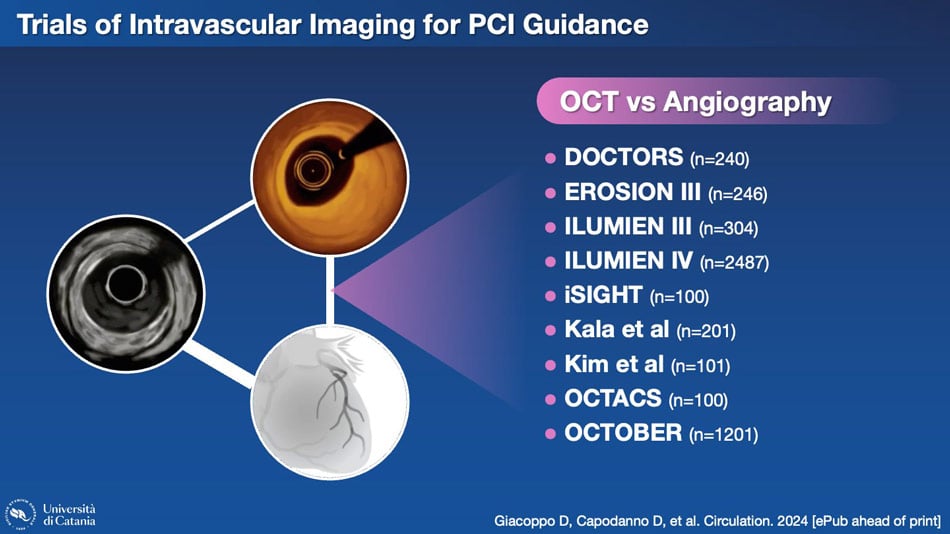

However, these are only two of the nine trials conducted to compare these two methodologies.

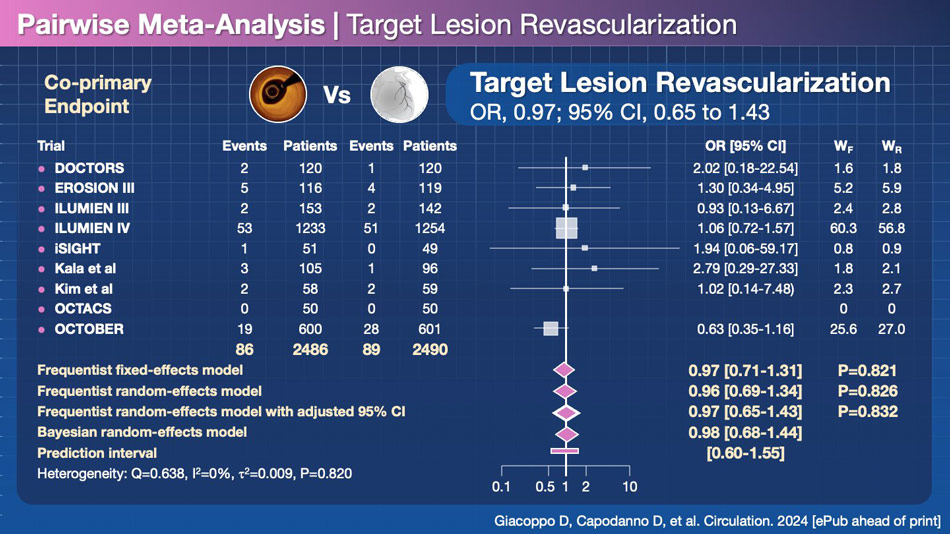

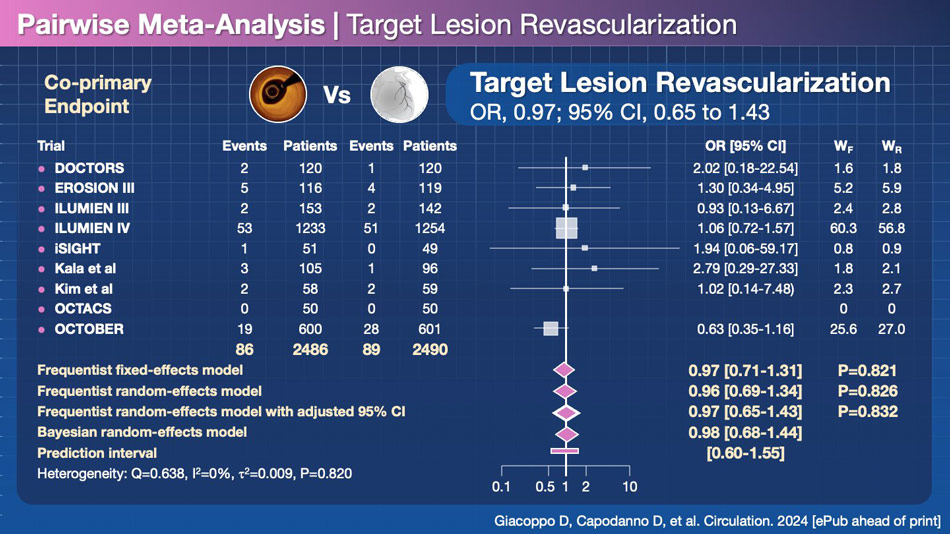

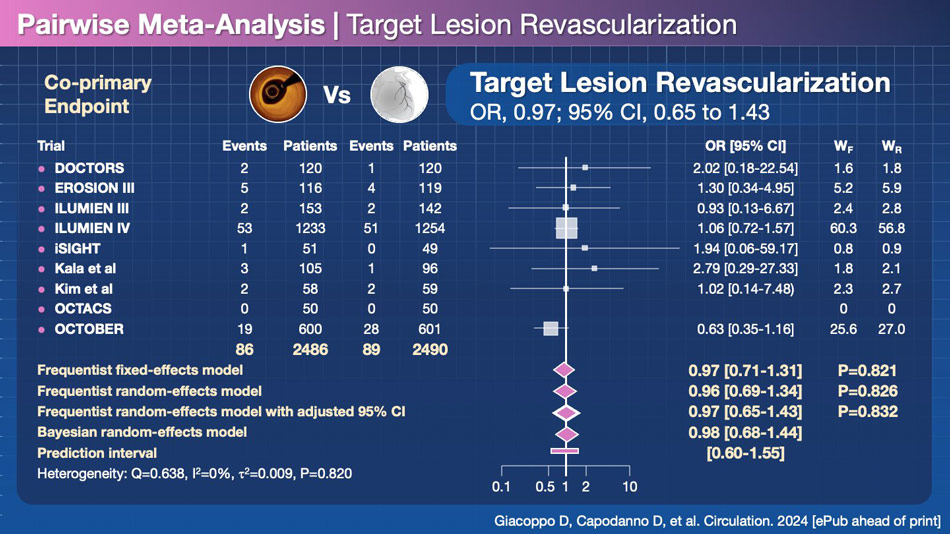

When combining all the trials, no significant difference emerges between OCT and angiography for reducing target lesion revascularization (TLR), which is arguably the most credible endpoint in terms of consistency of definition, aside from all-cause mortality.

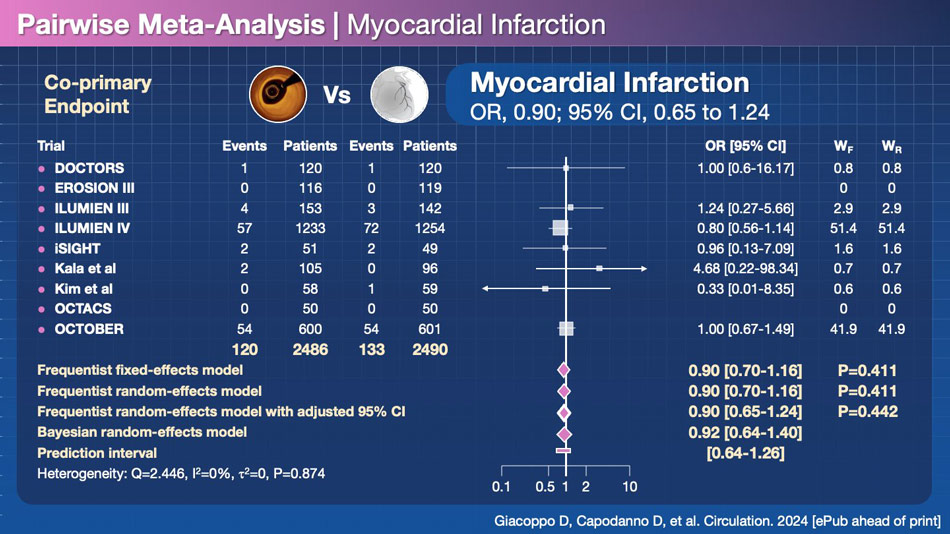

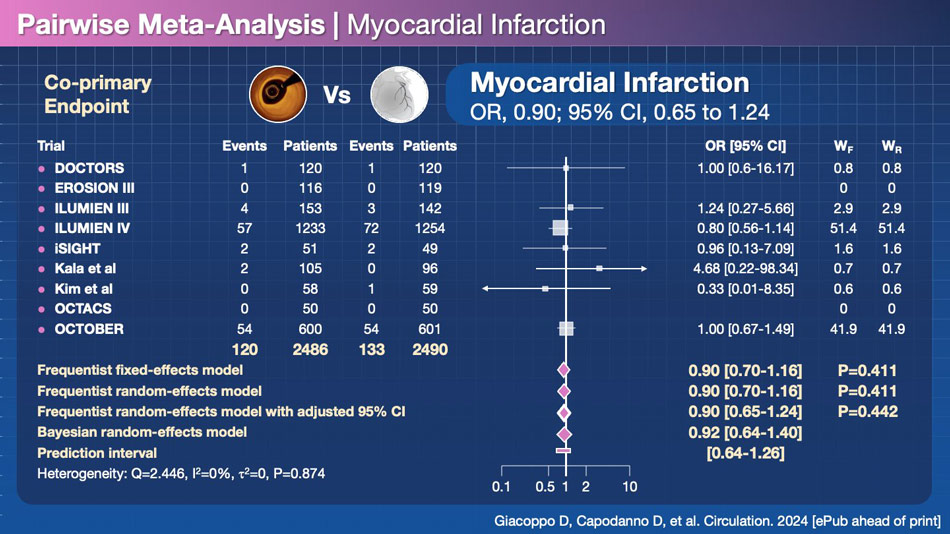

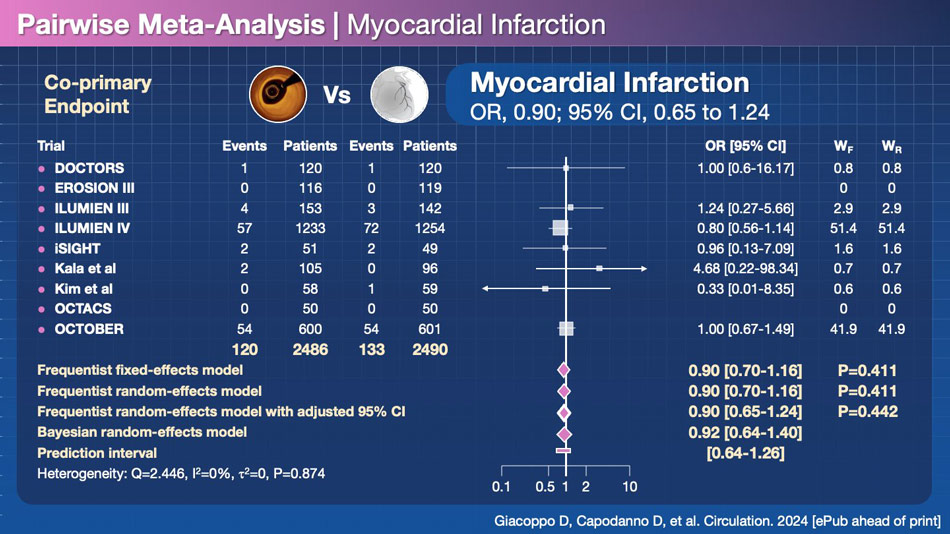

Furthermore, no difference is observed in terms of myocardial infarction, another endpoint with reasonably similar definitions across various trials, unlike target lesion failure (TLF) and major adverse cardiac events (MACE), which often have divergent definitions in different studies.

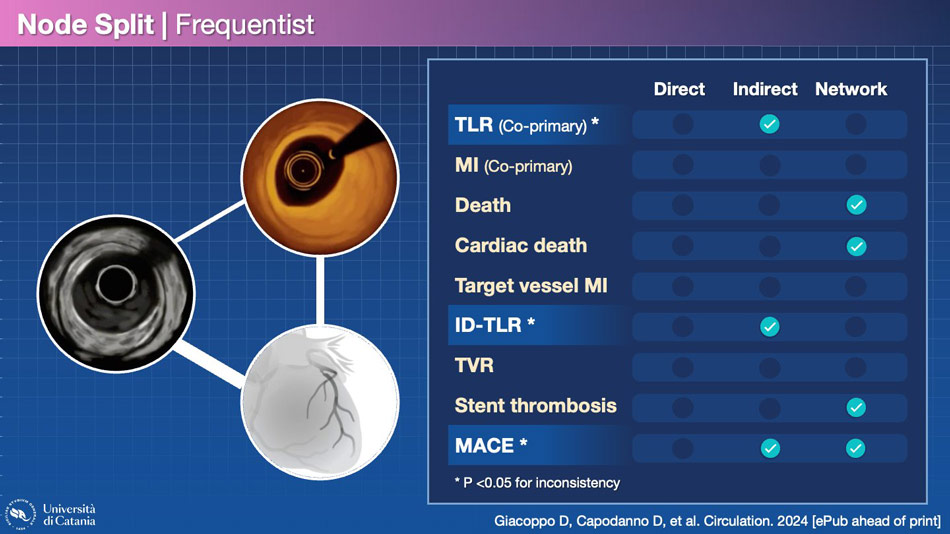

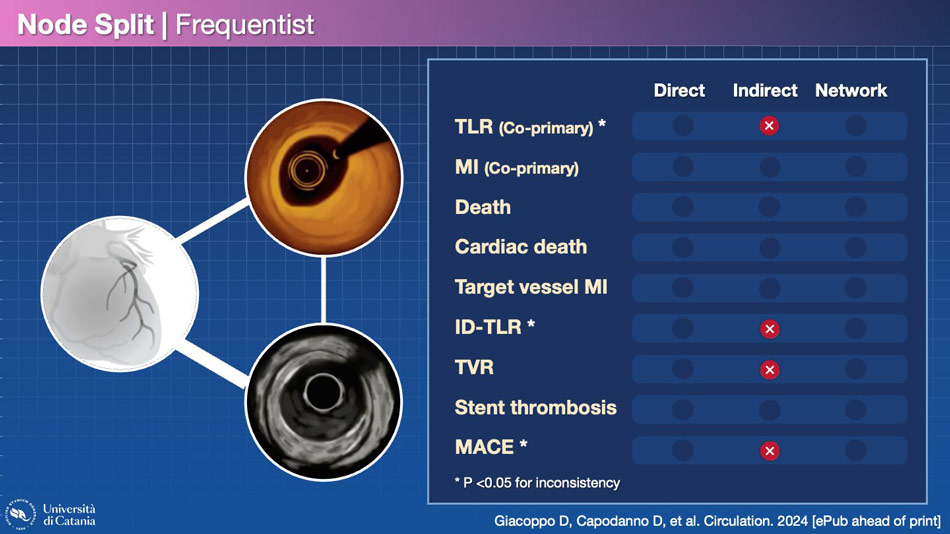

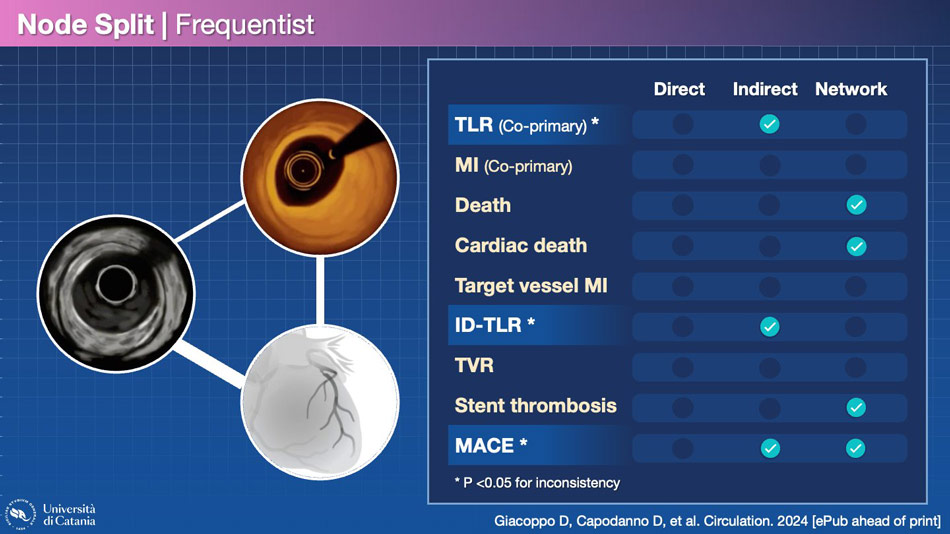

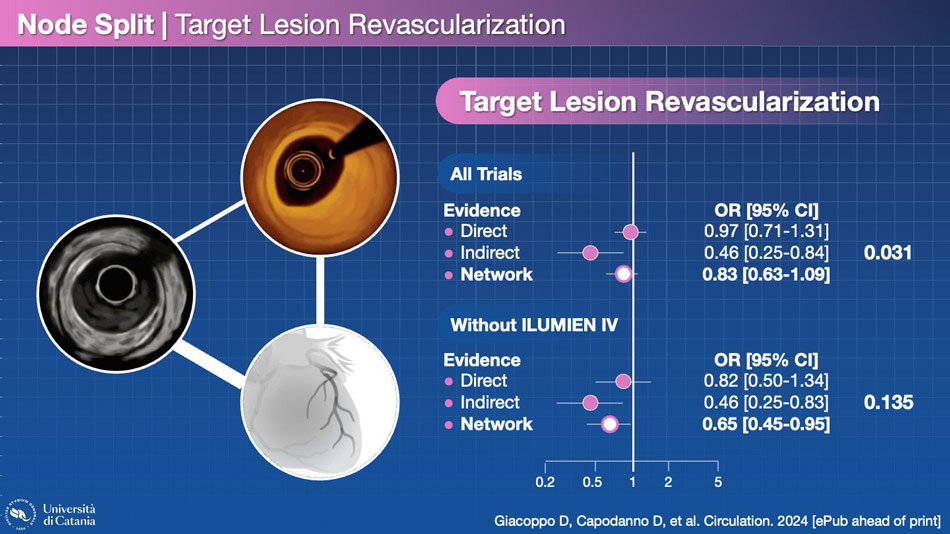

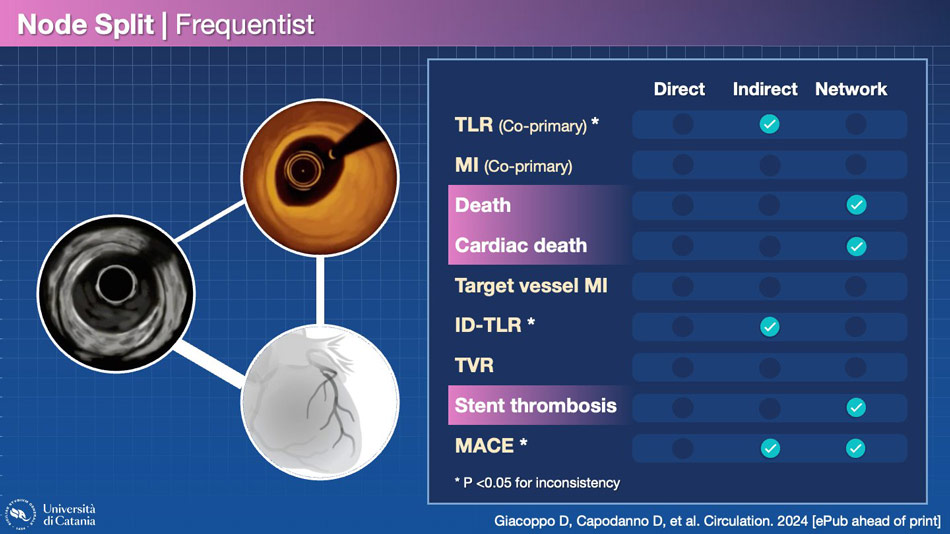

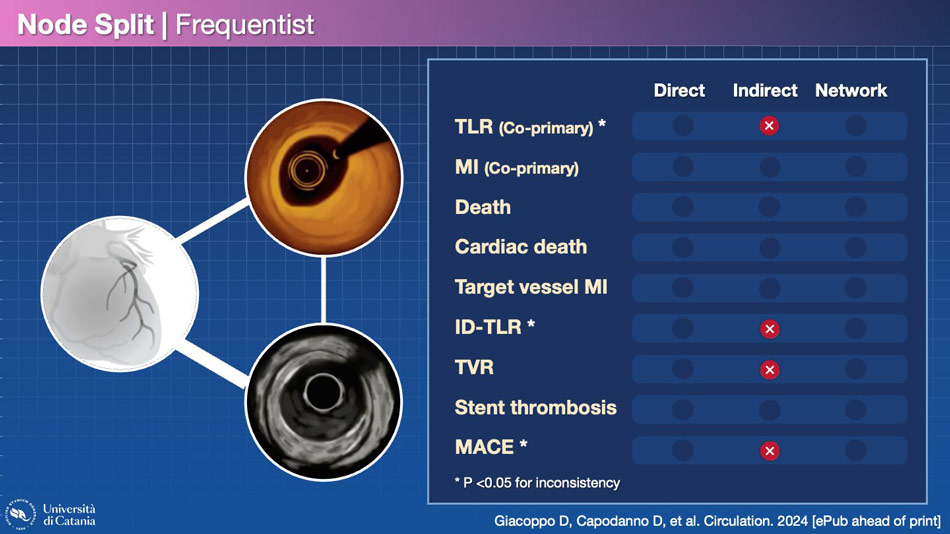

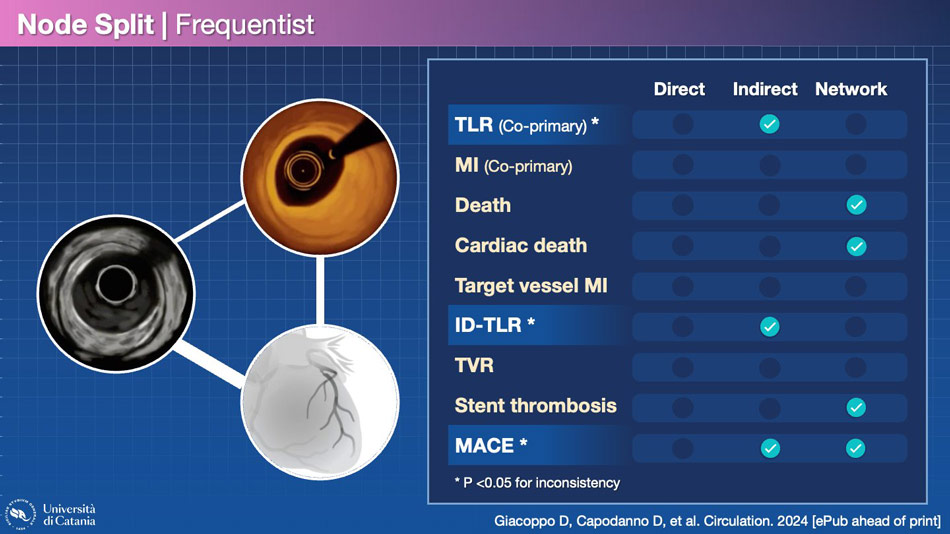

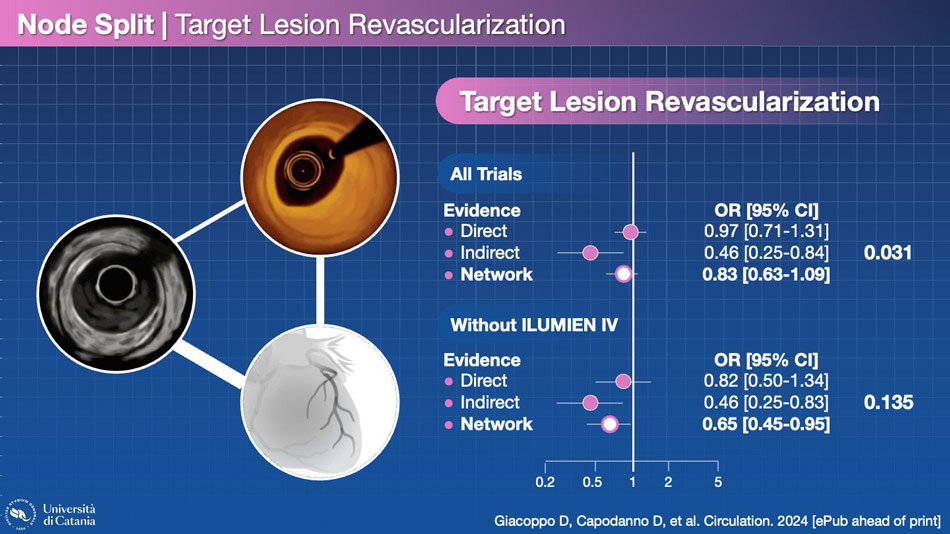

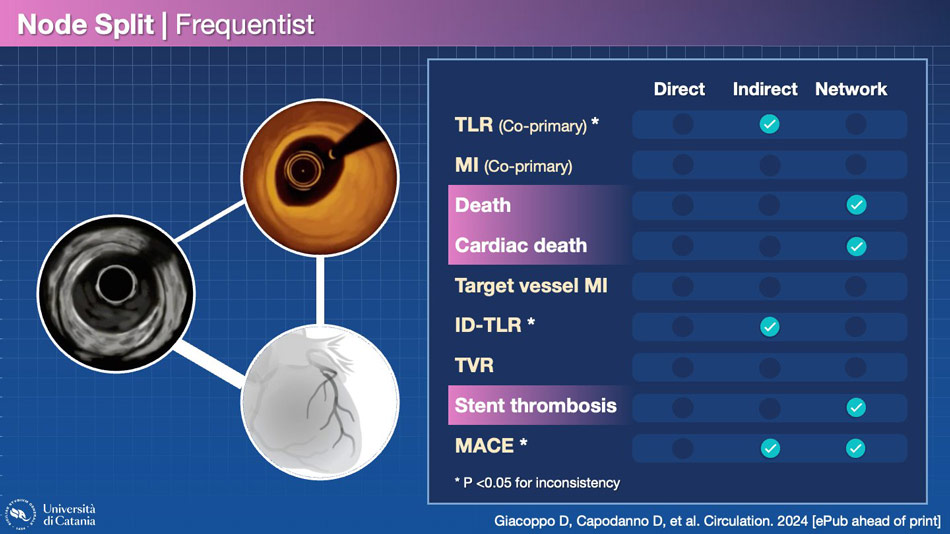

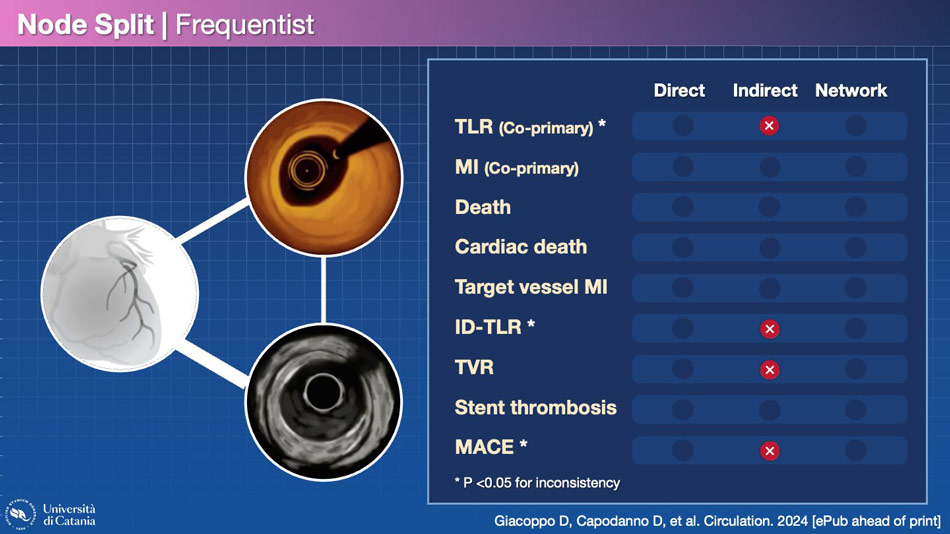

Upon distinguishing the results of the network analysis and verifying the consistency of direct and indirect analyses, several interesting findings emerge. Firstly, some endpoints exhibit significant inconsistency, rendering the network analysis less robust. This is the case for TLR, ischemia-driven TLR, and MACE.

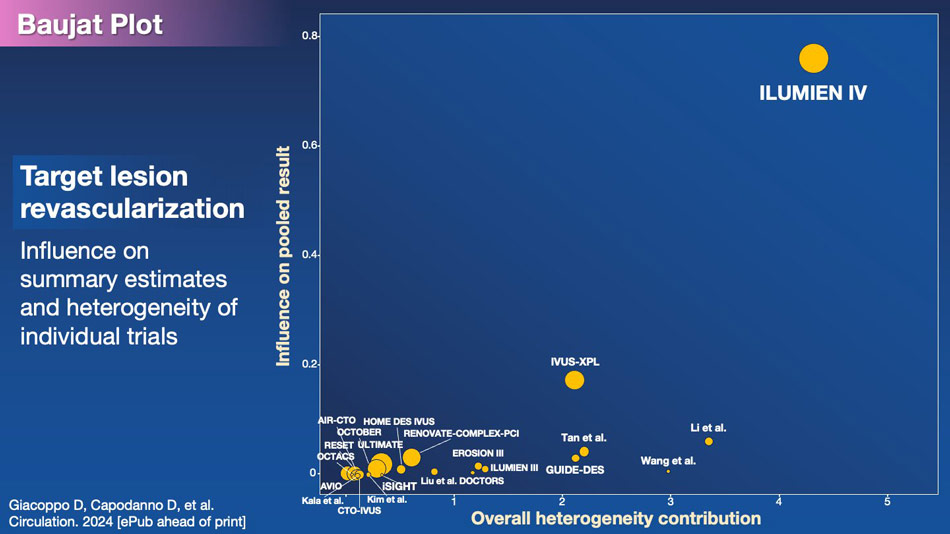

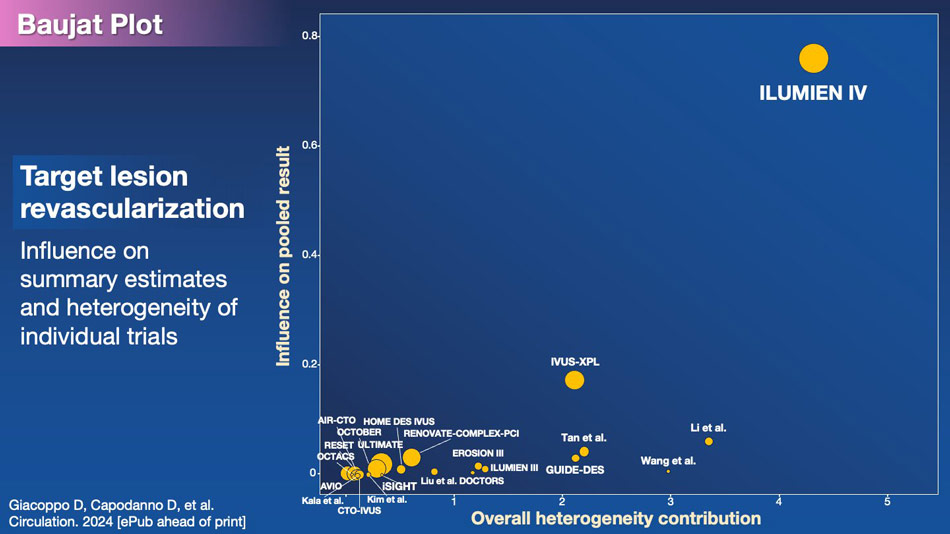

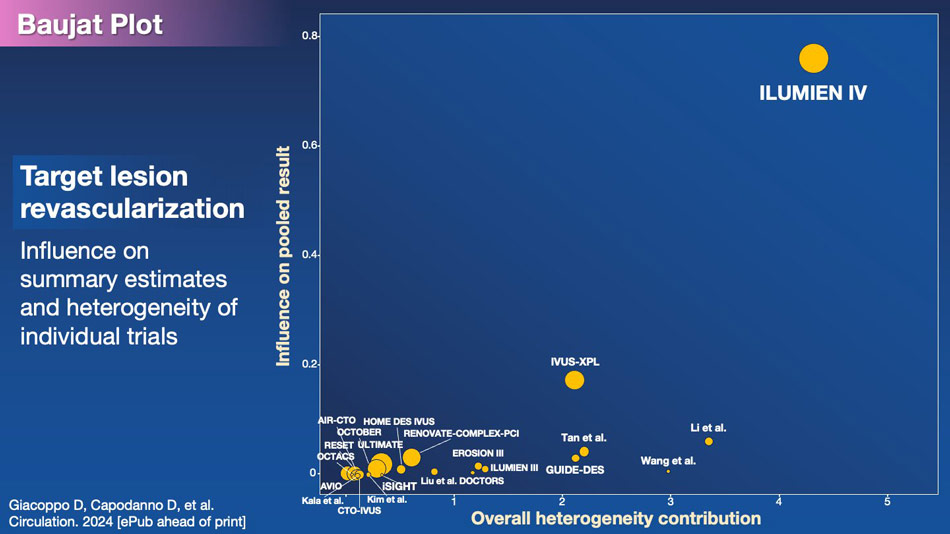

One trial, ILUMIEN IV, is evidently associated with this inconsistency, particularly concerning TLR. This becomes clear when plotting the influence on the outcome with the overall contribution to the heterogeneity of the meta-analysis.

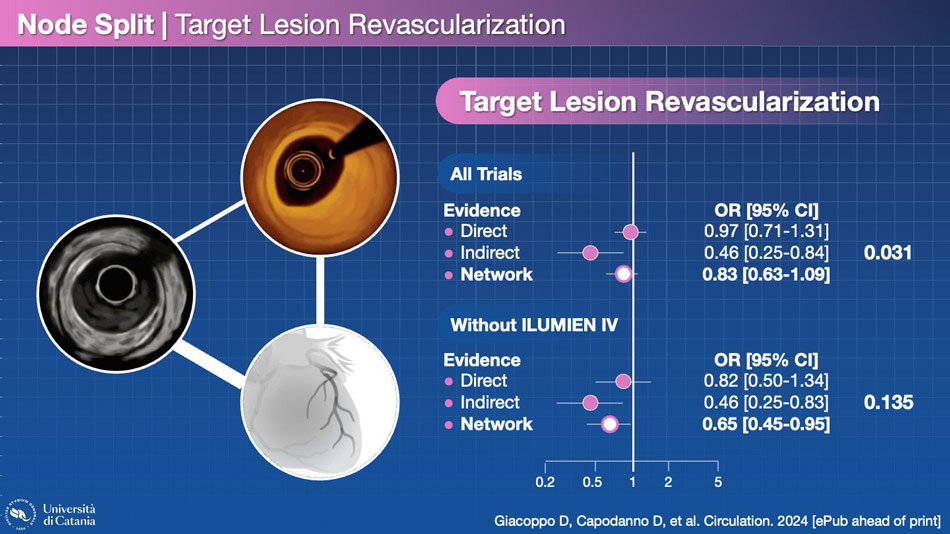

By removing ILUMIEN IV from the network, the inconsistency becomes non-significant. This is a decisive trial.

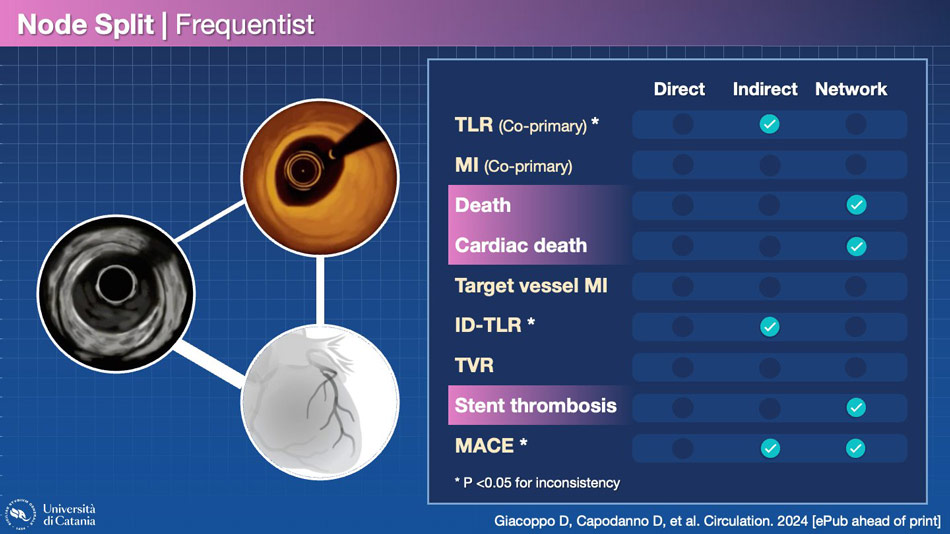

Other endpoints, such as all-cause death, cardiac death, and stent thrombosis, are significantly better with OCT in the network meta-analysis, without inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence. This enhances the credibility of the result. In the absence of significant reductions in myocardial infarction, the decrease in death and cardiac death may indeed be attributed to fewer sudden deaths, possibly due to stent thrombosis. It makes sense, but…

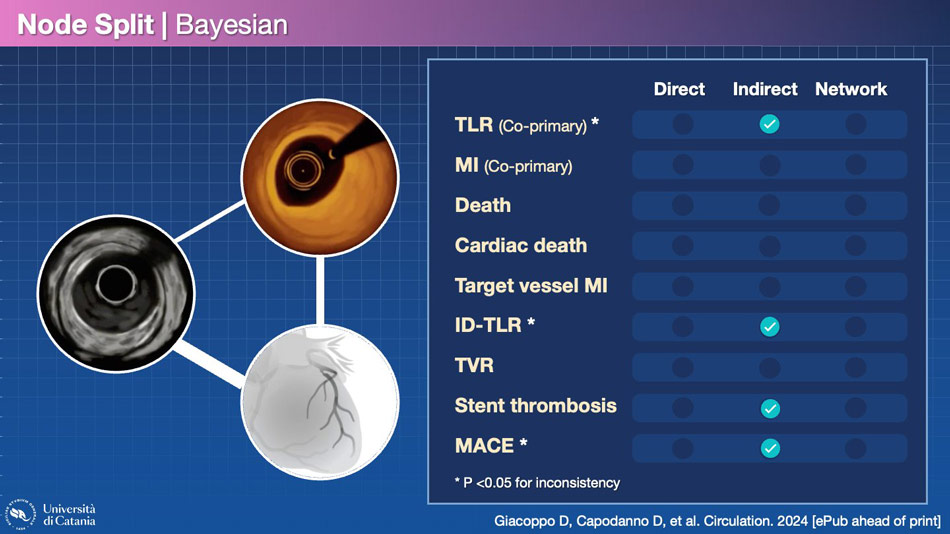

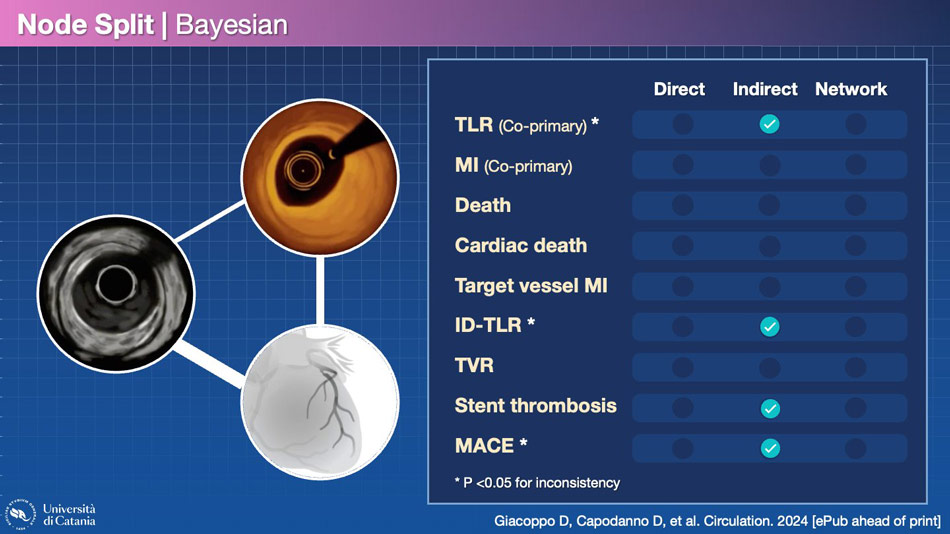

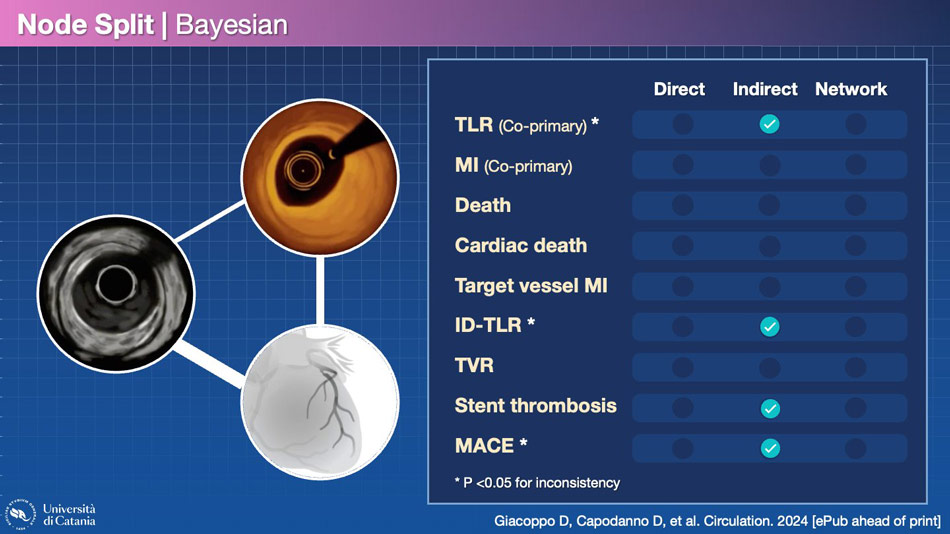

The result changes when the frequentist analysis becomes Bayesian. Bayesian inference is an approach to statistical inference where probabilities are interpreted not as frequencies but rather as levels of confidence in the occurrence of a given event. They are more conservative than frequentist approaches, so the fact that the two types of analyses yield different results implies the need to be cautious in drawing conclusions.

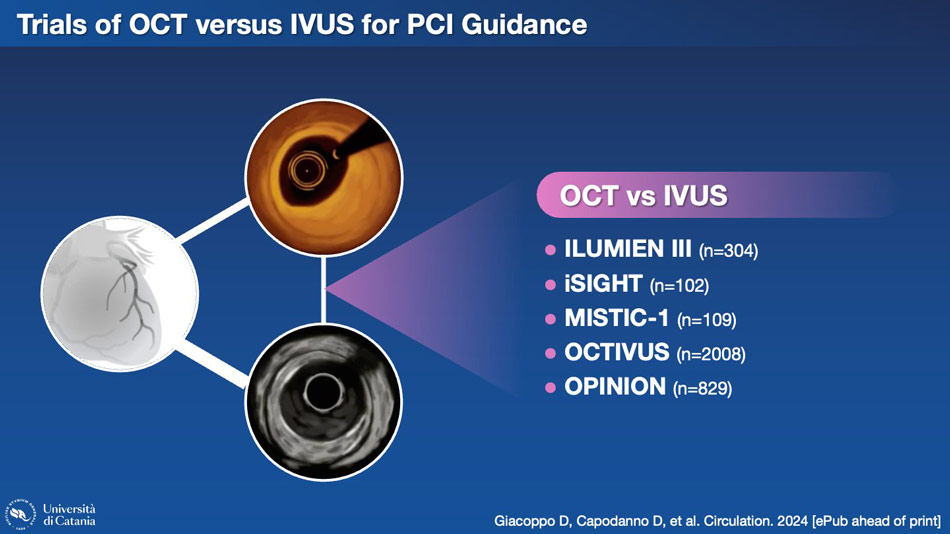

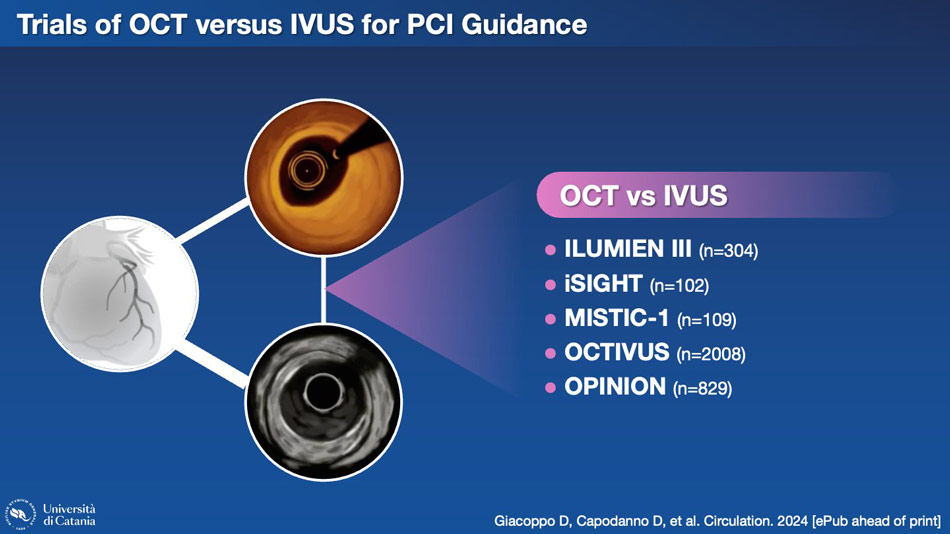

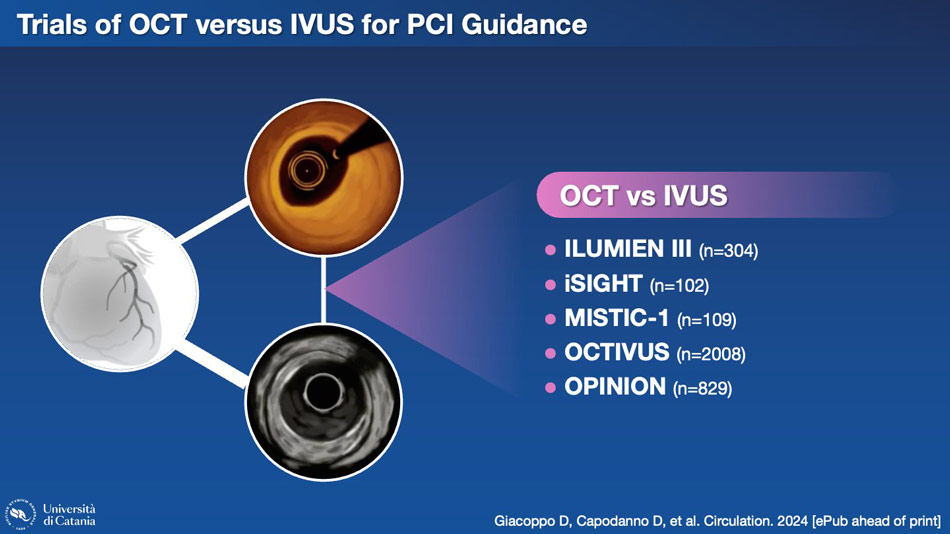

Another aspect worth considering is the node connecting OCT and IVUS in the network meta-analysis. Here, too, we have some trials with direct comparisons.

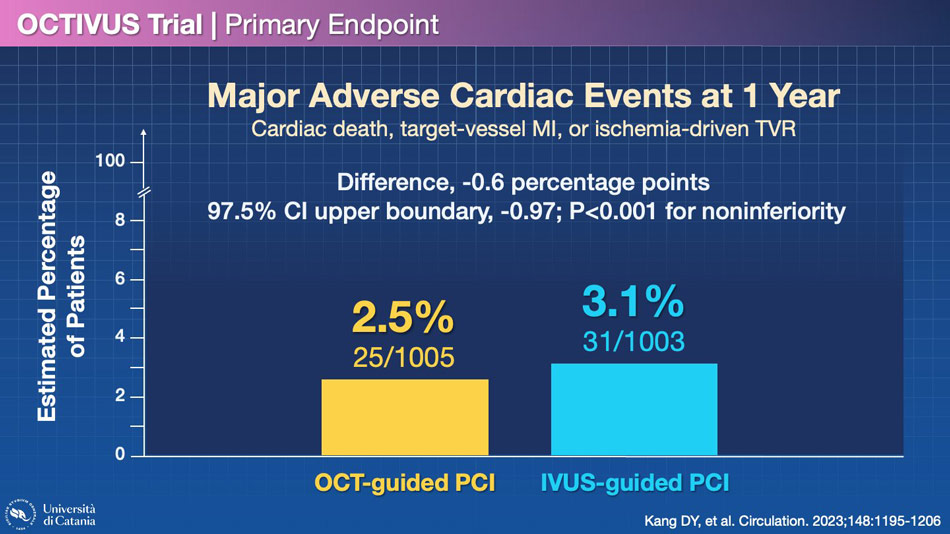

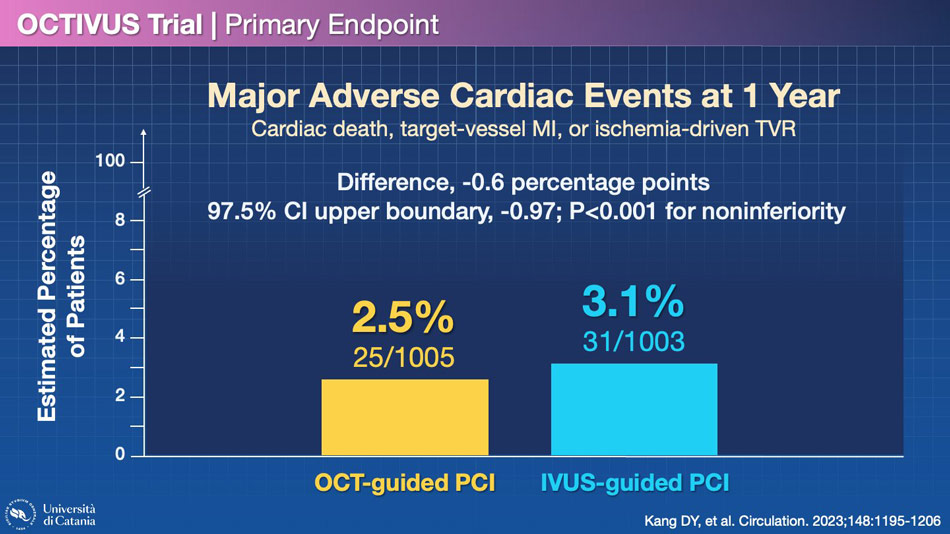

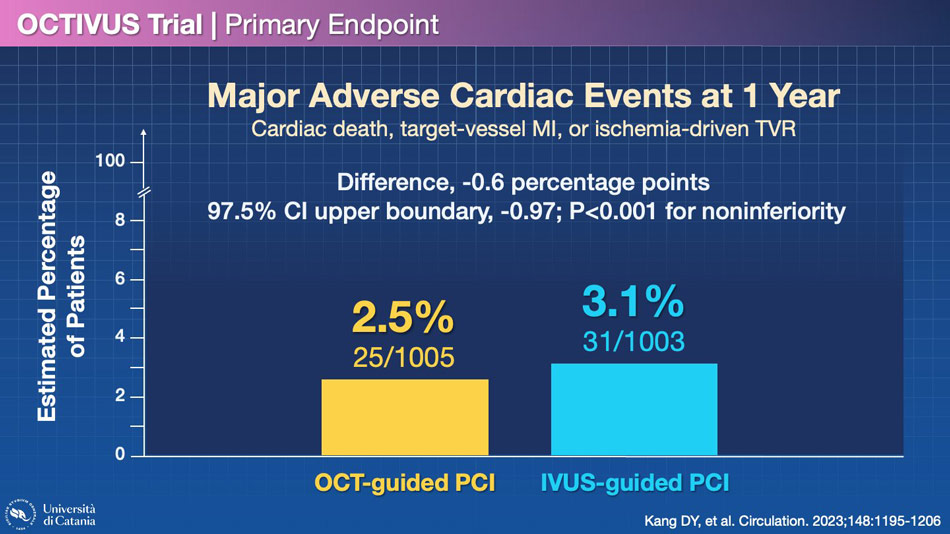

The largest trial in this space is called OCTIVUS, which demonstrated the non-inferiority of OCT compared to IVUS, although it should be noted that this study had fewer events than expected when the statistical hypothesis was formulated. However, the results were reasonably similar between OCT and IVUS.

If we consider again the network of the evidence, we find no significant difference between these two methodologies for each endpoint. The only differences emerge in the indirect analysis, but the inconsistency is generally significant, so I would not give too much weight to this result.

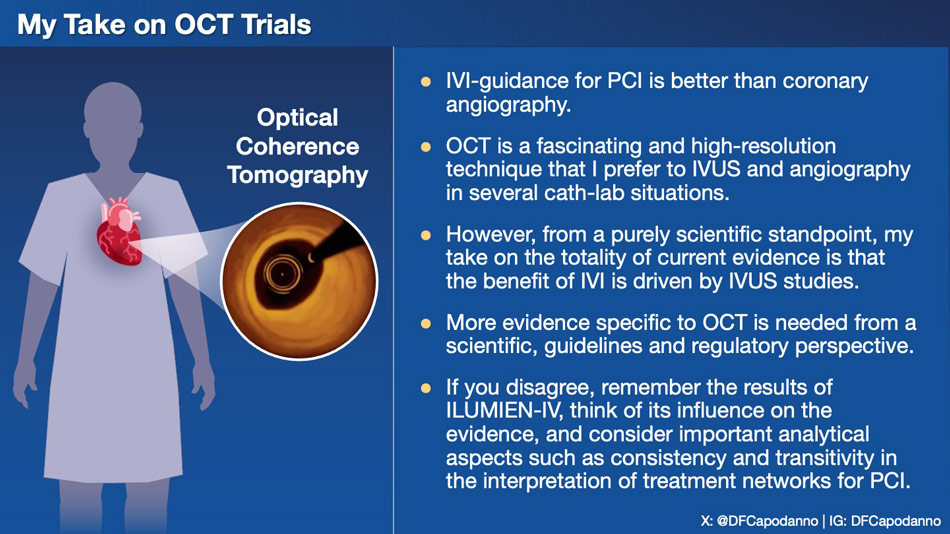

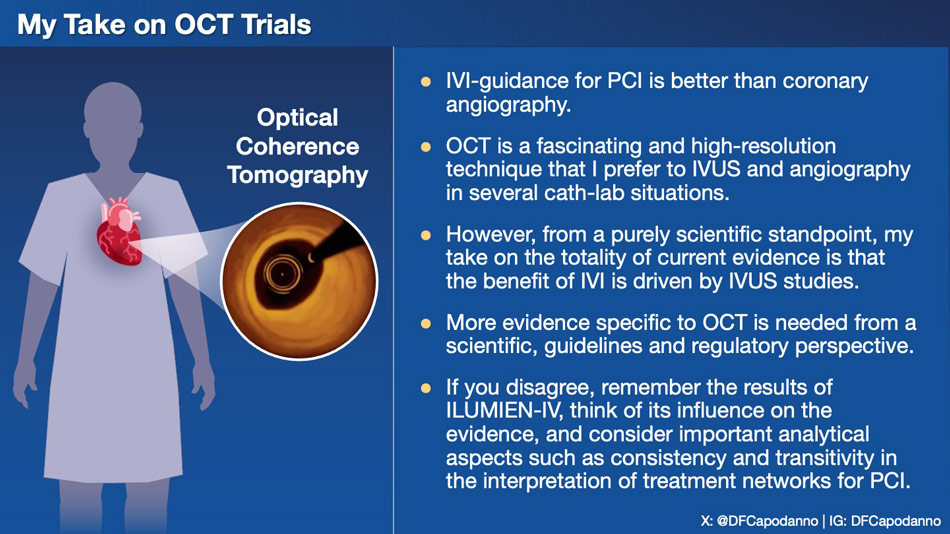

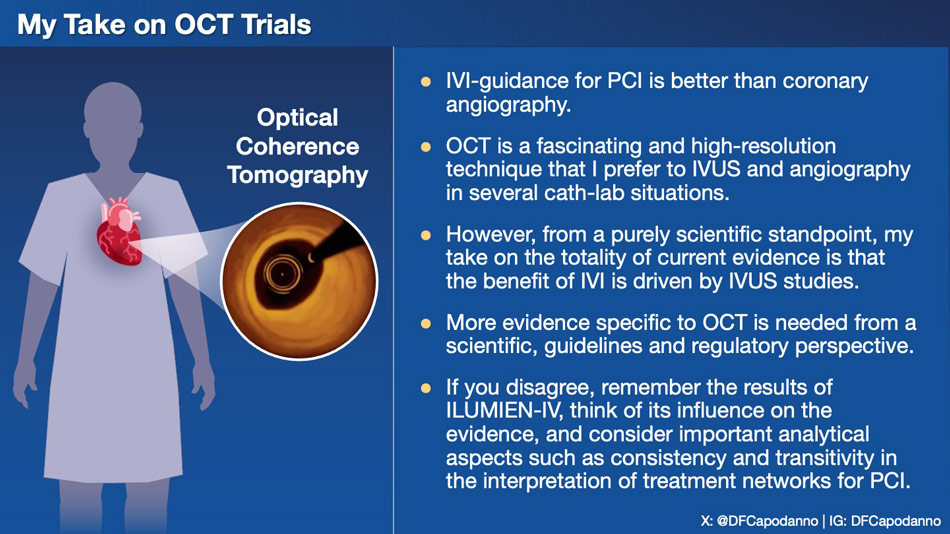

In conclusion, what can we take away from the results of OCT compared to angiography and IVUS? I believe that the practical aspect should be separated from the scientific aspect, especially in this case. OCT is an extraordinary tool for numerous applications, and for some of these, I find it preferable to IVUS. However, from an academic and somehow regulatory perspective, it cannot be denied that the OCT data are not yet entirely definitive (remember: ILUMIEN IV was neutral on TLF), and the indisputable evidence in favor of intracoronary imaging to guide our procedures is still mainly linked to IVUS trials.

Browse through these slides to find an analysis of recent OCT Trials.

From a historical perspective, four landmark trials have assessed strategies for functional or imaging guidance in PCI. FAME, IVUS-XPL, and FAVOR III established roles for FFR, IVUS, and QFR in 2009, 2015, and 2021, respectively, with a number needed to treat to avoid a cardiovascular event ranging between 20 and 34. However, in 2023, OCT in ILUMIEN IV missed its opportunity to do the same.

Given the numerous conducted trials and potential comparisons, there is an obvious temptation to conduct network meta-analyses. This study indicates that the probability of imaging ranking first, when compared with physiology and angiography, is higher for several clinical endpoints. Can we trust this result?

Several questions arise regarding network meta-analyses and their trustworthiness. In imaging, we have an interesting situation where a closed loop connects OCT, IVUS, and angiography, given all potential comparisons existing in the literature. When such closed loops exist, both direct and indirect comparisons can be considered. Reliable results hinge on the consistency between direct and indirect comparisons. If inconsistencies arise, relying on indirect evidence may lead to incorrect conclusions. Particularly, the transitivity assumption must be met. For example, if IVUS is superior to invasive coronary angiography, and OCT is similar to IVUS, then OCT must be superior to invasive coronary angiography. Is that the case?

Let's take a look at the trials that have compared OCT with angiography. The two main trials, ILUMIEN IV and OCTOBER, yielded different results. This is not surprising considering the numerous differences in patient characteristics and the type of coronary lesions that were treated.

However, these are only two of the nine trials conducted to compare these two methodologies.

When combining all the trials, no significant difference emerges between OCT and angiography for reducing target lesion revascularization (TLR), which is arguably the most credible endpoint in terms of consistency of definition, aside from all-cause mortality.

Furthermore, no difference is observed in terms of myocardial infarction, another endpoint with reasonably similar definitions across various trials, unlike target lesion failure (TLF) and major adverse cardiac events (MACE), which often have divergent definitions in different studies.

Upon distinguishing the results of the network analysis and verifying the consistency of direct and indirect analyses, several interesting findings emerge. Firstly, some endpoints exhibit significant inconsistency, rendering the network analysis less robust. This is the case for TLR, ischemia-driven TLR, and MACE.

One trial, ILUMIEN IV, is evidently associated with this inconsistency, particularly concerning TLR. This becomes clear when plotting the influence on the outcome with the overall contribution to the heterogeneity of the meta-analysis.

By removing ILUMIEN IV from the network, the inconsistency becomes non-significant. This is a decisive trial.

Other endpoints, such as all-cause death, cardiac death, and stent thrombosis, are significantly better with OCT in the network meta-analysis, without inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence. This enhances the credibility of the result. In the absence of significant reductions in myocardial infarction, the decrease in death and cardiac death may indeed be attributed to fewer sudden deaths, possibly due to stent thrombosis. It makes sense, but…

The result changes when the frequentist analysis becomes Bayesian. Bayesian inference is an approach to statistical inference where probabilities are interpreted not as frequencies but rather as levels of confidence in the occurrence of a given event. They are more conservative than frequentist approaches, so the fact that the two types of analyses yield different results implies the need to be cautious in drawing conclusions.

Another aspect worth considering is the node connecting OCT and IVUS in the network meta-analysis. Here, too, we have some trials with direct comparisons.

The largest trial in this space is called OCTIVUS, which demonstrated the non-inferiority of OCT compared to IVUS, although it should be noted that this study had fewer events than expected when the statistical hypothesis was formulated. However, the results were reasonably similar between OCT and IVUS.

If we consider again the network of the evidence, we find no significant difference between these two methodologies for each endpoint. The only differences emerge in the indirect analysis, but the inconsistency is generally significant, so I would not give too much weight to this result.

In conclusion, what can we take away from the results of OCT compared to angiography and IVUS? I believe that the practical aspect should be separated from the scientific aspect, especially in this case. OCT is an extraordinary tool for numerous applications, and for some of these, I find it preferable to IVUS. However, from an academic and somehow regulatory perspective, it cannot be denied that the OCT data are not yet entirely definitive (remember: ILUMIEN IV was neutral on TLF), and the indisputable evidence in favor of intracoronary imaging to guide our procedures is still mainly linked to IVUS trials.

"What next? I would like to see more OCT trials in patients with high procedural complexity, with standardized protocols, capable of analyzing whether the benefit exists beyond reasonable doubt and whether it is related to performing the test before stenting, after stenting, or in both phases."

Reference

Author

Interventional cardiologist / Cardiologist

Catania, Italy