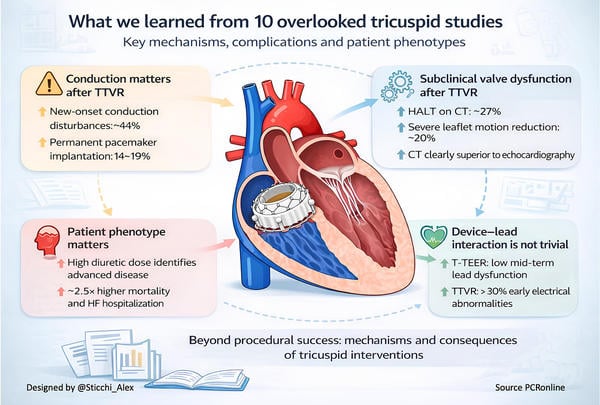

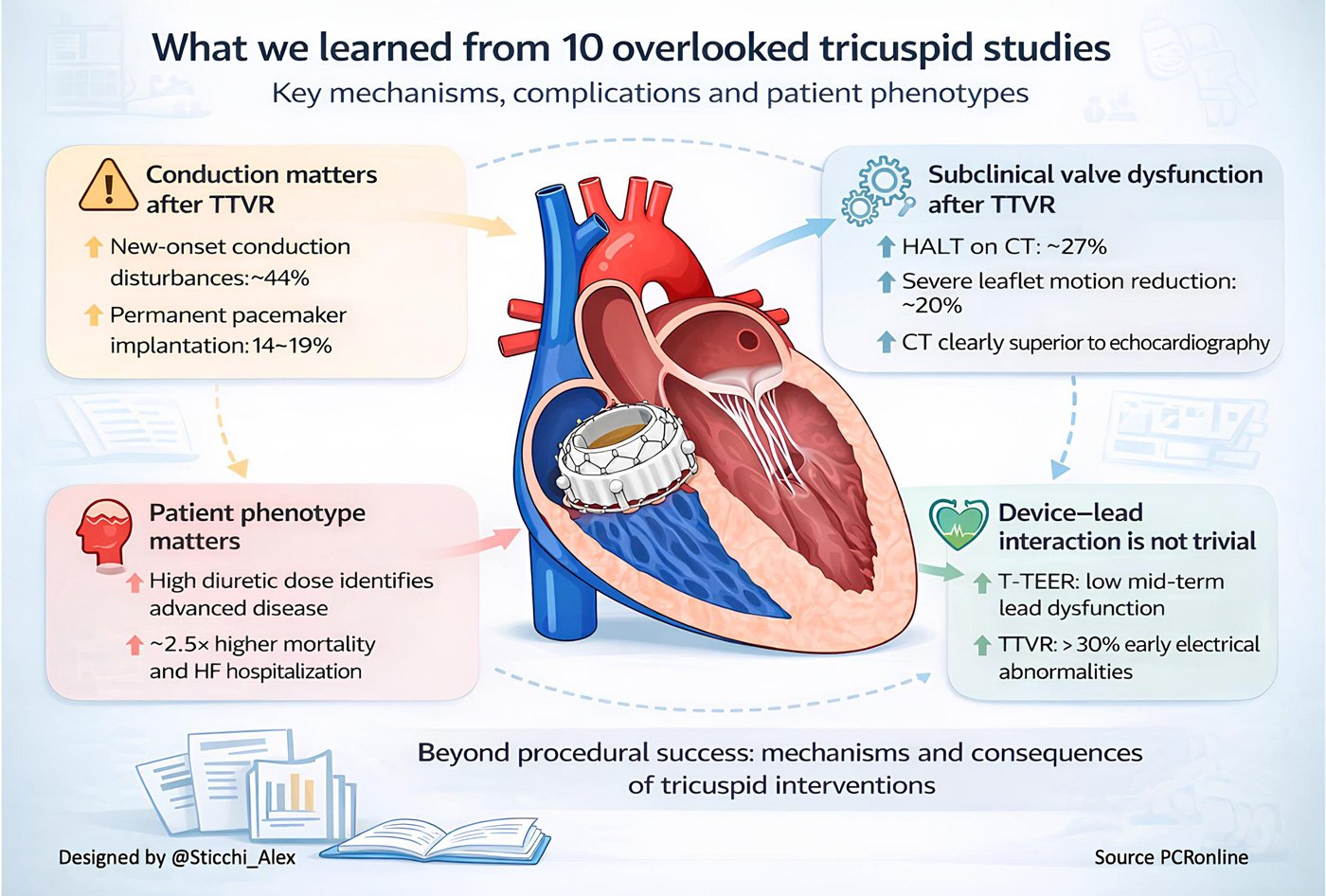

The top ten impactful papers from 2025 on tricuspid intervention we almost missed

A summar of impactful studies selected and reviewed by Alessandro Sticchi

Transcatheter interventions have rapidly reshaped the management of tricuspid valve disease, with landmark trials establishing feasibility and early clinical benefit.

Beyond these pivotal studies, a series of less visible but highly informative papers addressed mechanisms, complications, patient phenotypes, and unintended consequences of intervention.

This curated selection highlights ten impactful tricuspid studies that were almost missed, yet now help define a more integrated and physiology-driven approach to contemporary tricuspid care.

Paper (first author) | Population and design | Key numerical findings | Core message |

Le Ruz et al. (2025) 1 | 70 TTVR patients, single-center | NOCD 44.3%; PPM 14%; RV strain higher in NOCD+ (29.7% vs 25.1%, p=0.002) | Conduction disturbances after TTVR are frequent and mechanistically linked to RV function and device–septal interaction. |

Storozhenko et al. (2026) 2 | 146 T-TEER patients with RV leads | Lead dysfunction 6.8%; no fractures or reinterventions at ~2 years | RV lead entrapment during T-TEER is largely safe over mid-term follow-up. |

Abbasi et al. (2025) 3 | 32 TTVR patients with CIEDs | Lead abnormalities 31%; insulation breach 13%; revision 3%; >80% within 90 days | Lead jailing after TTVR often causes early electrical changes and requires close early surveillance. |

Peigh et al. (2025) 4 | 52 TTVR patients with entrapped RV leads | Major lead events 7.7%; early fractures/dislodgements | Clinically relevant lead complications after TTVR are uncommon but not negligible, especially early. |

Kempton et al. (2025) 5 | 45 TTVR patients with routine CT | HALT 27%; severe RLM 20%; higher gradients; reduced NYHA improvement | Subclinical valve thrombosis after TTVR is frequent and largely missed by echocardiography. |

Le Ruz et al. (2025) – Remodeling 6 | 80 TTVR patients, echo + CT | RVEDV −65%; LVEDV +17%; effective RVEF +65% | TTVR induces rapid and profound biventricular reverse remodeling. |

Marx et al. (2026) 7 | 225 TTVr patients | HDD mortality 44% vs 11%; HFH 22% vs 10%; HR 2.50 | High diuretic dose identifies an advanced TR phenotype with worse prognosis despite symptom relief. |

Chen et al. (2025) 8 | 159 TTVR patients (large vs small annulus) | Procedural success 81% vs 97%; clinical success 74% vs 95% | Large annuli reduce procedural success but not early safety after TTVR. |

Lurz et al. (2025) 9 | 20 heterotopic TTVR patients | Device success 100%; CVP −3 mmHg; NYHA improvement | Heterotopic cross-caval TTVR offers symptomatic benefit in otherwise untreatable patients. |

Angellotti et al. (2025) 10 | 176 real-world EVOQUE TTVR | TR ≤ mild 98.4%; NYHA I–II 20%→80%; PPM 18.9% | Real-world TTVR is highly effective but associated with a relevant pacemaker burden. |

Abbreviations: TTVR = transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement; TTVr = transcatheter tricuspid valve repair; T-TEER = tricuspid transcatheter edge-to-edge repair; TR = tricuspid regurgitation; RV = right ventricle; RA = right atrium; NOCD = new-onset conduction disturbances; PPM = permanent pacemaker implantation; CIED = cardiac implantable electronic device; HALT = hypoattenuated leaflet thickening; RLM = reduced leaflet motion; CT = computed tomography; HFH = heart failure hospitalization; HDD = high diuretic dose; CVP = central venous pressure.

Critical thinking across the ten papers

These ten studies collectively document a clear transition of the tricuspid field into a replacement era. Real-world commercial data show that orthotopic TTVR can deliver near complete TR elimination at scale, with TR reduced to mild or less in 98.4 % at 30 days, and a major shift in symptoms, with NYHA I–II increasing from 20 % to 80 %10. In parallel, mechanistic and imaging studies clarify that the consequences of abruptly removing a chronic right-sided volume load are not simply procedural, but deeply physiological. After TTVR, RV volumes shrink rapidly while LV filling increases, with RVEDV decreasing by 65 % and LVEDV increasing by 17 %, alongside a marked rise in effective RV performance, with effective RVEF increasing by 65 % and RV coupling by 20 %6. This redefines what “success” means in TR, moving from a valve-centric target to a biventricular and systemic target.

The price of consistent TR elimination is a distinct complication signature that is now impossible to ignore. Conduction disturbances are not rare noise. In a dedicated mechanistic cohort, new-onset conductance disturbances occurred in 44.3 % within 30 days and 14 % required a pacemaker, with predictors that are plausibly modifiable by technique and planning, such as device contact with the membranous septum1. Real-world TTVR confirms that pacemaker implantation is a recurring issue, with 18.9 % of pacemaker-naive patients requiring pacing at 30 days and baseline conduction disease conferring higher risk10. This should shift pre-procedural evaluation toward a conduction risk framework rather than treating pacemaker implantation as an acceptable, unspecific collateral effect.

The lead story is equally paradigm-shaping because it forces the field to accept that many TTVR candidates will arrive with transvenous RV leads and that “jailing” is often unavoidable. The data suggest a nuanced reality. In TEER, interaction with RV leads appears clinically permissive, with low rates of meaningful electrical deterioration and no fractures or reinterventions over mid-term follow-up2. In contrast, in EVOQUE TTVR, lead abnormalities occur in approximately one third of patients, largely driven by R-wave sensing changes, but with a clinically important minority showing patterns consistent with insulation breach, and occasional need for revision3. A larger multicenter dataset confirms that major lead-related clinical events are uncommon but real, with a small number of dislodgements and fractures, typically emerging early in the post-procedural course4. Taken together, this does not argue against TTVR in patients with CIEDs, but it decisively argues against complacency. “Lead jailing” is not a single strategy. It is a spectrum that requires standardised pre-procedure electrophysiology involvement, explicit informed consent language, and a post-procedure surveillance plan that is front-loaded in the first 60 to 90 days, when most abnormalities declare themselves3,4.

Thrombosis and subclinical valve dysfunction represent another “almost missed” domain that can quietly erode patient benefit if the field does not adopt systematic detection strategies. CT-based analyses demonstrate that HALT and reduced leaflet motion are common after TTVR, with moderate-to-severe HALT in 27 % and severe CT-defined RLM in 20 %, both associated with higher gradients and less symptomatic improvement at 30 days5. Importantly, transthoracic echocardiography is relatively insensitive, failing to detect a substantial proportion of severe cases identified on CT5. This pushes the field toward a practical question with immediate consequences: whether selected CT surveillance should become part of early post-TTVR care pathways, at least in patients with suboptimal early symptom response, rising gradients, or unexpected hemodynamic patterns.

Another shared message across the papers is that patient selection in TR must incorporate systemic disease severity and not merely anatomic feasibility. The diuretic dose analysis provides a pragmatic and widely available signal of advanced congestion biology. A baseline loop diuretic dose above 95 mg furosemide-equivalent identified a higher-risk phenotype with poorer procedural success and markedly worse 1-year outcomes, including 44 % mortality versus 11 %, yet still with symptom improvement without diuretic escalation in many patients7. This creates a future-facing framework. Diuretic escalation is not simply symptom management. It may be an alarm bell for the timing of intervention, and it may also help define when intervention risks becoming “too late” to meaningfully change prognosis.

Finally, the portfolio of technologies is expanding beyond a single orthotopic pathway. Orthotopic replacement dominates because it delivers consistent TR elimination, but it remains constrained by anatomy, comorbidity, and the complication profile. Heterotopic approaches such as cross-caval valve replacement with Trillium illustrate a different strategic aim, treating the systemic venous consequences of TR rather than the valve itself, with 100 % technical success, a median CVP reduction of 3 mmHg, and early functional improvement in patients deemed unsuitable for other options9. This is not merely a niche solution. It signals that the future of TR therapy may become architecture-based: orthotopic replacement for those who can tolerate it and benefit from complete TR elimination, heterotopic approaches for those in whom the priority is decompression of systemic congestion and symptom relief when orthotopic solutions are not feasible.

What we learned from 10 overlooked tricuspid studies

References

- Le Ruz R, Nazif T, George I, et al. New-Onset Conductance Disturbances After Transcatheter Tricuspid Valve Replacement: A Mechanistic Assessment. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2025; 18: 2569–79.

- Storozhenko T, Russo G, Vanderheyden M, et al. Tricuspid Right Ventricular Lead Entrapment in Transcatheter Tricuspid Interventions: The Tri-LEAD Study. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2025; published online Dec. DOI:10.1016/J.JACEP.2025.11.003.

- Abbasi M, Killu AM, Van Niekerk C, et al. Device-lead abnormalities and function after transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement. Europace 2025; 27. DOI:10.1093/EUROPACE/EUAF219.

- Peigh G, Al-Kazaz M, Davidson LJ, et al. Outcomes of Entrapped Right Ventricular Pacing or Defibrillator Leads Following Transcatheter Tricuspid Valve Replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2025; 18: 1762–72.

- Kempton H, Stolz L, Stocker T, et al. Hypoattenuated Leaflet Thickening and Reduced Leaflet Motion After Transcatheter Tricuspid Valve Replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2025; published online Oct. DOI:10.1016/j.jcin.2025.10.026.

- Le Ruz R, Agarwal V, George I, et al. Cardiac Remodeling After Transcatheter Tricuspid Valve Replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2025; published online Nov. DOI:10.1016/j.jcin.2025.10.023.

- Marx L, Finke K, Althoff J, et al. Relationship between Diuretic Dose and Outcome Following Transcatheter Tricuspid Valve Repair for Severe Tricuspid Regurgitation. Can J Cardiol 2025; published online Dec. DOI:10.1016/J.CJCA.2025.12.014.

- Chen F, Yang X, Qiao F, et al. Comparison of Early Outcomes Following Transjugular Transcatheter Tricuspid Valve Replacement Between Large vs Small Annulus. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2025; published online Dec. DOI:10.1016/J.JCIN.2025.11.013.

- Lurz P, Kresoja KP, Besler C, et al. Heterotopic Crosscaval Transcatheter Tricuspid Valve Replacement for Patients With Tricuspid Regurgitation: The Trillium Device. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2025; 18: 1425–34.

- Angellotti D, Mattig I, Samim D, et al. Early Outcomes of Real-World Transcatheter Tricuspid Valve Replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2025; 18: 1896–909.

No comments yet!