204 results

Impact of complete revascularisation in relation to left ventricular function in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and multivessel disease: a post hoc analysis of the COMPLETE randomised trial

05 Feb 2026

This study represents a prespecified subgroup analysis of the COMPLETE randomised trial, a large, international, randomised controlled study comparing a strategy of complete revascularisation with culprit-only percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and multivessel coronary artery disease (MVD).

The present...

Reviewer

Reviewer

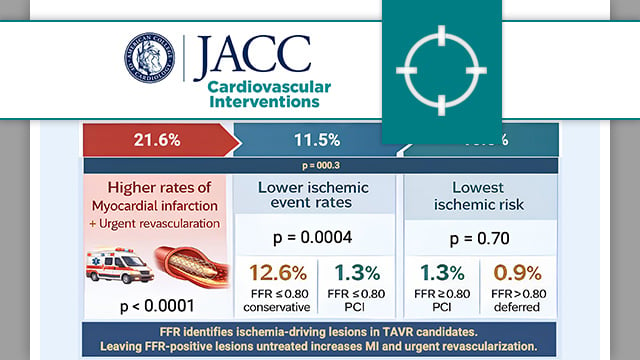

Fractional flow reserve to guide revascularisation in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing TAVR

07 Jan 2026

The present analysis compared major adverse cardiac events in patients with significant coronary stenosis (FFR ≤ 0.80 or visual stenosis ≥ 90 %) versus those with non-significant stenosis (FFR > 0.80).

Reviewer

Reviewer

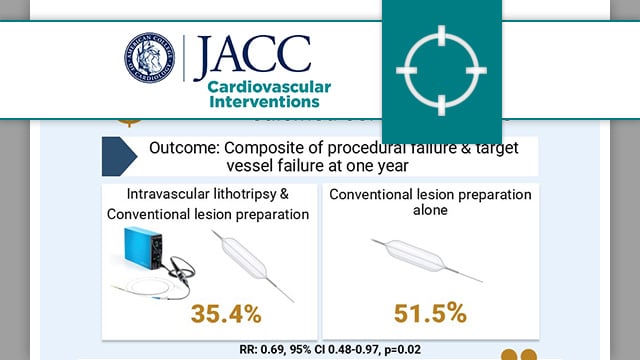

Balloon lithotripsy added to conventional preparation before stent implantation in severely calcified coronary lesions

06 Jan 2026

In patients with severely calcified coronary lesions undergoing PCI, the BALI trial evaluated the benefit of the addition of intravascular lithotripsy to conventional lesion preparation on the composite endpoint of procedural failure and target vessel failure.

Reviewer

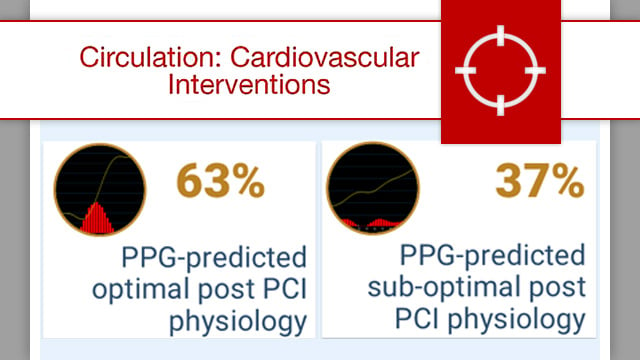

Impact of pullback pressure gradient on clinical outcomes after percutaneous coronary interventions

02 Dec 2025

While FFR traditionally reflects the severity of a lesion at a fixed location, PPG incorporates the pullback profile, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of disease distribution.

Reviewer

Reviewer

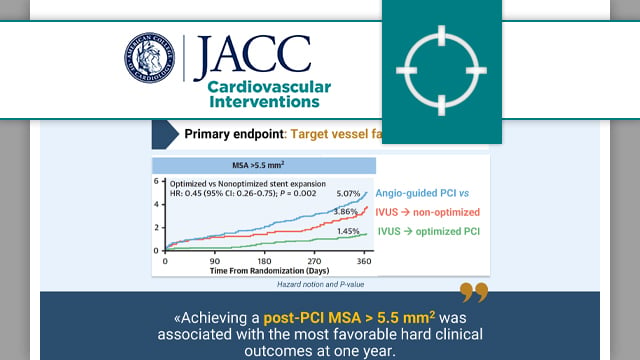

Validation of intravascular ultrasound-defined optimal stent expansion criteria for favorable 1-year clinical outcomes

17 Nov 2025

This individual patient data analysis of the three largest RCTs evaluating IVUS-guided stent optimisation showed that an MSA > 5.5 mm2 was associated with reduced TVF at one year.

Reviewer

Reviewer

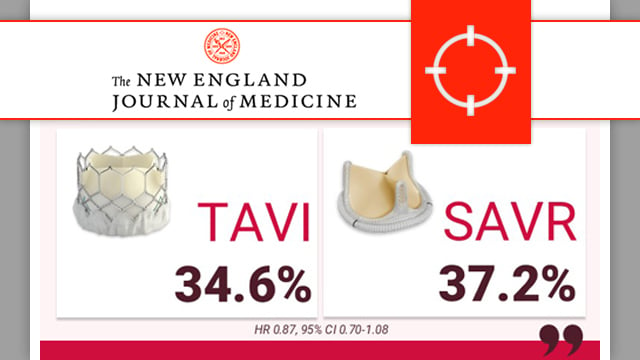

PARTNER 3: transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement in low-risk patients at 7 years

14 Nov 2025

At 7 years, low-risk patients affected by severe symptomatic aortic valve stenosis 1:1 randomly treated by SAPIEN 3 TAVI or surgery showed similar clinical outcomes and late valve durability

Reviewer

Reviewer

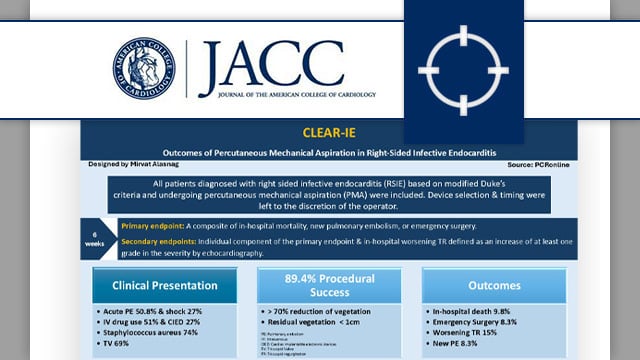

CLEAR-IE: outcomes of percutaneous mechanical aspiration in right-sided infective endocarditis

06 Oct 2025

Can mechanical aspiration offer a safer, less invasive option for managing right-sided infective endocarditis? The CLEAR-IE registry provides valuable early insights.

Reviewer

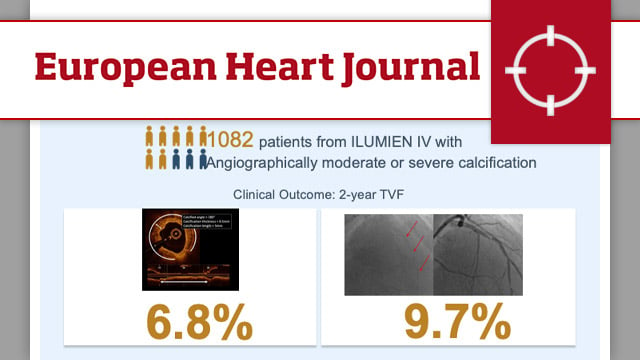

Optical coherence tomography- vs angiography-guided coronary stent implantation in calcified lesions: the ILUMIEN IV trial

28 Aug 2025

In the overall population (n = 2,114), there was a significant interaction between the effect of randomisation to OCT guidance vs angiography guidance in lesions with moderate/severe calcification (n = 1,082) vs no/mild calcification (n = 1,032) on the 2-year rate of TVF (Pinteraction = 0.01).

Reviewer

One- versus three-month DAPT after everolimus-eluting stent implantation in diabetic patients at high-bleeding risk: results from the XIENCE Short DAPT programme

17 Jun 2025

This analysis from the XIENCE Short DAPT programme compared the safety and efficacy of one-month versus three-month DAPT in high-bleeding risk patients with and without diabetes mellitus (DM) following PCI with everolimus eluting stents (EES).

Reviewer

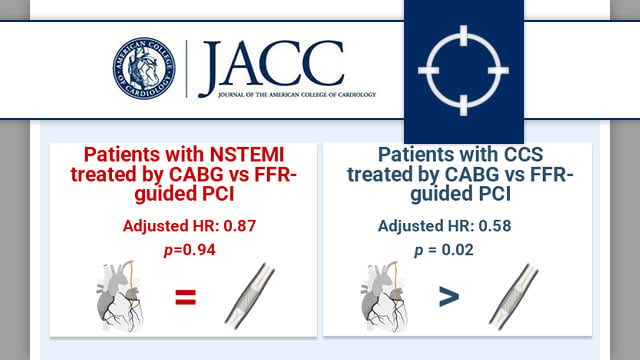

Outcomes after CABG compared with FFR-guided PCI in patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome

10 Jun 2025

This prespecified analysis of the Fractional Flow Reserve versus Angiography for Multivessel Evaluation (FAME 3) trial examined the impact on cardiovascular outcomes of treatment by CABG versus FFR-guided PCI in patients with three vessel disease (3-VD), stratified by acute (NSTEMI) or chronic coronary syndrome (CCS) presentation.

Reviewer

Reviewer