Impact of pullback pressure gradient on clinical outcomes after percutaneous coronary interventions

Selected in Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions by E. Gallinoro , N. Ryan

While FFR traditionally reflects the severity of a lesion at a fixed location, PPG incorporates the pullback profile, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of disease distribution.

References

Authors

Kazumasa Ikeda; Takuya Mizukami; Koshiro Sakai; Frederic Bouisset; Jeroen Sonck; Adriaan Wilgenhof; Hitoshi Matsuo; Toshiro Shinke; Hirohiko Ando; Masahiro Hada; Brian Ko; Simone Biscaglia; Fernando Rivero; Thomas Engstrøm; Antonio Maria Leone; Lokien X. van Nunen; William F. Fearon; Evald Høj Christiansen; Stephane Fournier; Liyew Desta; Andy Yong; Julien Adjedj; Javier Escaned; Masafumi Nakayama; Ashkan Eftekhari; Danielle Keulards; Frederik M. Zimmermann; Tatyana Storozhenko; Bruno R. da Costa; Gianluca Campo; Colin Berry; Damien Collison; Thomas W. Johnson; Daniel Munhoz; Tetsuya Amano; Divaka Perera; Allen Jeremias; Ziad A. Ali; Takashi Kubo; Kazuhiro Satomi; Nobuhiro Tanaka; Bernard De Bruyne; Nils P. Johnson; Carlos Collet

Reference

Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions New online https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.125.016022

Published

Originally Published 25 October 2025

Link

Read the abstractReviewers

Our Comment

Reviewer. E.Gallinoro.

Source: PCRonline.com

Why this study – the rationale/objective?

Despite an angiographically successful PCI, up to one-third of patients continue to exhibit suboptimal coronary physiology, which is associated with worse clinical outcomes.

The Pullback Pressure Gradient (PPG) enables assessment of the disease pattern (focal vs diffuse) and has previously been shown to predict post-PCI fractional flow reserve (FFR). However, whether this physiological prediction translates into differences in long-term clinical outcomes had not yet been established.

How was it executed? The methodology

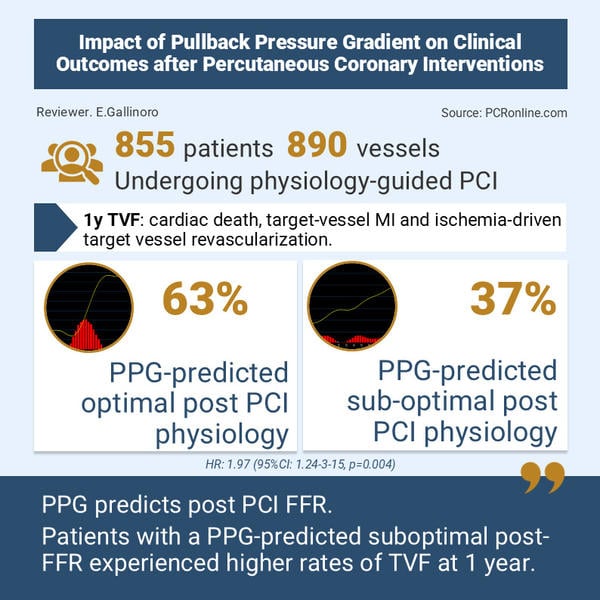

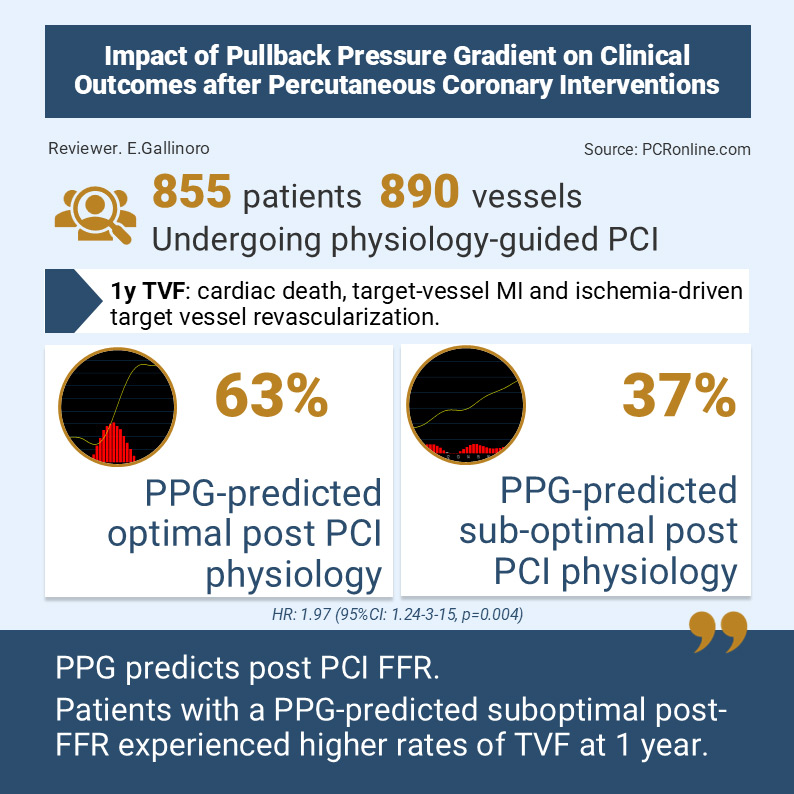

This was a post- hoc analysis of the international, multicentre PPG Global registry including 855 patients (890 vessels) undergoing PCI. A pre-PCI physiology-based predictive model incorporating baseline FFR, PPG and vessel type was applied to estimate post-PCI FFR. Vessel-specific thresholds (0.83 for LAD and 0.93 for non-LAD) were used to classify predicted physiological outcome as optimal or suboptimal.

The primary endpoint was one-year target vessel failure (TVF), defined as a composite of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction (MI) and ischemia-driven target vessel revascularisation (TVR). Peri-procedural MI was defined according to the Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction.

What is the main result?

There was strong agreement between predicted and measured post-PCI FFR (r = 0.65; ΔFFR r = 0.92; mean difference 0.001). Predicted suboptimal physiology was associated with significantly higher TVF (12.9 % vs 6.9 %; adjusted HR, 1.97 [95 % CI, 1.24–3.15]; p = 0.004), target-vessel MI (10.4 % vs 6.4 %, adjusted HR, 1.88 [95 % CI, 1.14–3.11]; p = 0.014) and a fivefold increase in ischemia-driven TVR (2.5 % vs 0.4 % adjusted HR, 5.56 [95 % CI, 1.12–27.6]; p = 0.036). This association remained significant after exclusion of periprocedural MI, with a higher risk of TVF in the predicted suboptimal physiology group (adjusted HR, 3.31 [95 % CI, 1.11–9.86]; = 0.031).

Critical reading and the relevance for clinical practice:

The introduction of PPG to quantify the pattern of coronary disease (focal, diffuse, or mixed) has transformed the concept of FFR from a single-point measurement to a longitudinal assessment of disease. While FFR traditionally reflects the severity of a lesion at a fixed location, PPG incorporates the pullback profile, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of disease distribution. Previous studies demonstrated that PPG predicts post-PCI FFR, and the present work further expands its role from a purely diagnostic tool to a prognostic one. Importantly, PPG is available before stent implantation, allowing not only identification of focal versus diffuse phenotypes, but also stratification of patients according to their likelihood of truly benefiting from PCI.

A particularly striking finding is that measured post-PCI FFR — when categorised as optimal or suboptimal using predefined thresholds — did not correlate with clinical outcomes, as event rates were similar between groups. This reinforces a recurring challenge: unlike pre-PCI FFR, no universally accepted post-PCI FFR threshold exists, as highlighted by conflicting data from registries and meta-analyses. These results suggest that baseline disease pattern and physiological substrate may be more clinically relevant than final procedural metrics alone.

Another key observation relates to outcomes stratified by disease phenotype. In the present study, patients with diffuse disease required longer and smaller stents, increasing procedural complexity and risk of periprocedural MI, particularly in LAD lesions due to side-branch occlusion. Notably, results remained consistent even after excluding periprocedural MI, indicating that the higher risk observed in patients with predicted suboptimal physiology is likely driven by both procedural risk and subsequent stent failure, reflected in higher spontaneous MI and target vessel revascularisation rates.

Conversely, patients with predicted optimal physiology demonstrated excellent prognosis (< 1 % TVF when excluding periprocedural MI), reinforcing that not all haemodynamically significant lesions carry equal prognostic weight. This supports the concept of precision PCI, in which physiology-based profiling could guide interventional strategy, lesion preparation, or even consideration of non-stent-based therapy.

Although external validation is required, this study establishes the foundation for future physiology-driven individualisation of PCI beyond angiographic optimisation alone and suggests that alternative strategies — such as drug-eluting balloon therapy or intensified medical management — may warrant investigation in patients with functionally diffuse disease.

No comments yet!