14 May 2024

lmaging: The eyes of the Heart Team

More than ever, Heart Team members rely on advanced imaging to guide procedures and aid in decision-making about patient selection and management. Just as imaging plays a prominent role in the cathlab, so it will be central to this year's EuroPCR content, with a track of specially designed 'Focus on Imaging' sessions where participants will be able to enhance their individual modality and multimodality imaging skills, covering both coronary and valvular interventions. Here experts tell us about the special place their 'favourite' modality holds in the cathlab with some thoughts for the future.

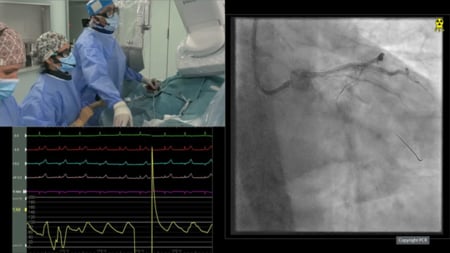

Intracoronary imaging

Introduced in the 1980s, intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) was the first intracoronary imaging technique to be developed to overcome the 2D limitations of angiography. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) was introduced a few years later in the 1990s. Both have made significant contributions to our current understanding of CAD by their capacity to obtain in viva images of the vessel wall structure. In addition, IVUS has played a critical role in the establishment of modern stent deployment technique. In the 1990s, rates of stent thrombosis and anticoagulant complications were high. Using IVUS, it became clear that stents were being incompletely deployed, prompting a switch to using high-pressure balloon dilation and optimised anticoagulation, which helped ensure adequate stent expansion and considerably reduced periprocedural complications from then on.

Huge technological advances have been seen over the years in two main directions: the technique - with the development of tiny catheters - and the resolution. Building on grey-scale IVUS, high-definition IVUS significantly improved spatial resolution and additional advances have included faster acquisition and powerful signal processing with improved software to facilitate image interpretation and reliable measurements. OCT is often favoured over IVUS for its higher spatial resolution, although this comes at the expense of a reduced penetration depth into tissue. Combining IVUS and OCT, with the introduction of hybrid IVUS/OCT catheters, is an exciting breakthrough.

Despite the benefits, the adoption of IVUS and OCT to guide PCI has been heterogeneous across the world. For example, while rates of IVUS use are high in Japan, Korea and Hong Kong, they are low in Europe and USA, with incredible differences in its use for the same indication. Nowadays, preferential use of these modalities is given to complex procedures for complex lesions, which are becoming more frequent with the shift towards an increase in patients' age, comorbidities and levels of calcification and with the ambition of interventional cardiologists to approach difficult settings including the left main, diffuse long disease and bifurcations. An increase in the use of intracoronary imaging may also be seen with the rise of drug-coated balloons in patients with ACS given the limitations of angiography in optimising results.

For all procedures it is important to plan ahead, anticipate that intracoronary imaging will be needed and use it to map out your route from baseline to finish. A long set-up time is often cited as an excuse against its use, but with the latest technology and good team collaboration, today's modern systems take a very short time to set up. Another major barrier to wider use is a mental one - the operator believes they are good enough not to need it. In fact, there is now insurmountable evidence that intravascular imaging is better than coronary angiography for complex procedures. Although OCT is lagging behind IVUS somewhat in the amount of accumulated positive data, both are superior to angiography alone, and their value should not be doubted.

Now we have the new technology, I think it is time to develop the next generation of interventional cardiologists who are trained sufficiently that they are keen to use intracoronary imaging and that they are able to accurately interpret its findings. Increased education in physiology and intracoronary imaging for earlycareer interventionalists, particularly practical training, is essential if we are to take our procedures to the next level.

"Since the beginning, imaging has changed interventional cardiology - it showed us that our strategies for stent deployment were suboptimal. lntracoronary imaging helped change our practice then and it can help us achieve the best possible outcomes now."

What is the bright spot on OCT? M2 or anti-inflammatory macrophages!

Submitted by Tanuj Bhatia, SGRR Medical and Health Sciences College, Uttarakhand, lndia

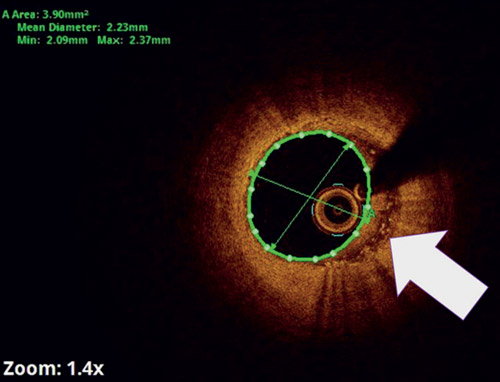

Interventional echocardiography

As the field of transcatheter structural heart interventions has exploded over recent years, so has the need for proper assessment over each stage of the continuum of care. Cardiac surgeons can see the structure that they are going to repair or replace directly, but interventionalists only see the structure on fluoroscopy. Echocardiography, most commonly transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE), adds the soft tissue resolution to the fluoroscopy - it becomes the eyes of the interventionalists.

Echocardiography is often the first imaging technique used in patients with suspected structural heart disease. Other imaging modalities may then be used to refine the diagnosis in terms of the severity and extent of the disease. And when it comes to the procedure, the growing use of the term 'interventional echocardiography' reflects that the echocardiographer is now firmly embedded as a 'coproceduralist' and a highly valued member of the procedural team. As the procedure begins, it is important that the echocardiographer is familiar with all the technical aspects, including the types of catheters/sheaths/wires and dilators, to anticipate the next steps. Effective communication among the procedural team is a critical component of success and begins when the imager relays important preprocedural findings to the interventionalists. Because the imager sees the structure or the anatomical landmark orientation differently to the interventional cardiologist, a common language and learning from each other is essential. Fusion imaging is rising in popularity as we appreciate the value of close integration of information obtained through various imaging modalities, aligning them in both time and space. For instance, overlaying TOE images onto fluoroscopic projections can provide improved visual guidance for the interventionalists and facilitates communication between imagers and interventionalists during procedures.

Although most often used now for imaging the mitral and tricuspid valves, many cathlabs have an echocardiography machine there if needed to detect complications during TAVI.

"Echocardiography is probably the first imaging technique used to diagnose complications, acting as a kind of safety net for the entire interventional team."

Echocardiography has also become an important part of postprocedural assessment, to check the outcome, to see if there has been reversal of cardiac damage or remodelling and to assess any complications, such as pericardia! effusion or paravalvular leakage. And it has many subsequent uses, for example, evaluating durability, whether the prosthesis is still functioning and if there are any signs of degeneration. Other modalities may then be used to help guide patient management.

As the field of interventional echocardiography continues to expand, so does the need for in-depth education and training. I highly recommend the session with the PCR Tricuspid Focus Group on how to best image atrioventricular valves.

What do you see? A giant pseudoaneurysm of the inferior LV wall revealed at LV gram was confirmed by an echocardiogram.

Submitted by Attilio Restivo and colleagues from Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli, Metropolitan City of Rome Capital and ASST Papa Giovanni XXIII Hospital

Province of Bergamo, Italy

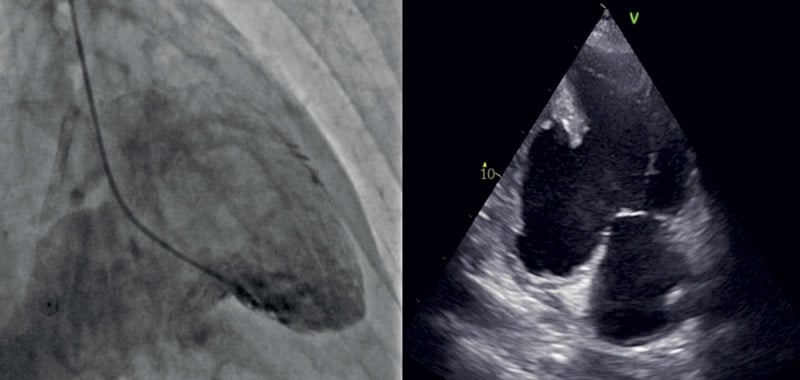

Computed tomography

Computed tomography (CT) for structural heart interventions

In 1990, Agatston et al. reported their seminal findings on the quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast CT.1

Since then, cardiac CT has been exploited for its diagnostic and prognostic abilities, haemodynamic assessment of coronary artery lesions, monitoring the progression of coronary atheroma and perivascular/adipose tissue evaluation. With the introduction of TAVI, the CT scan now plays a critical role in the field of structural heart interventions. A preprocedural CT scan can provide important information about peripheral vascular access, device sizing and optimal fluoroscopic viewing angles to improve device delivery and positioning. These benefits are now being extrapolated for such procedures as transcatheter mitral and tricuspid valve interventions, left atrial appendage occlusion and paravalvular leak treatment. Within a much shorter space of time, the operator learns the perfect views to go from one structure to another, they understand exactly where to position the device and this also increases operator confidence.

CT as a learning tool

Whether it's ultrasound beams, X-rays or magnetic resonance - all modalities slice the heart in similar ways. The beauty of the CT scan is that it can provide a 4-dimensional volume data set to help us fully understand the anatomy and can be used as a tool to better understand multimodality imaging. I would suggest that interventional cardiologists "play" with the multi-planar reconstruction tool on CT and appreciate the positioning of various cardiac structures across the different chamber views. This knowledge can then be applied to echocardiography or fluoroscopy. So rather than the operator having to do thousands of procedures to build up a picture in their minds and use anecdotal knowledge from other procedures, CT accelerates their learning and everything they do becomes intentional without guesswork.

CT for PCI and CABQ - "Back to the future"

Since 1977, fluoroscopy has provided adequate imaging to guide PCI. In the early 1980s, it was anecdotal experiences that led to "optimal" fluoroscopic viewing angles that are still used today. Until recently, however, not much thought had been given to CT-guided fluoroscopic viewing angles for PCI as we do for structural heart interventions. With increasing use of diagnostic coronary CT, the interventional cardiologist will have additional data at hand. More specifically, the operator will be able to identify patient-specific fluoroscopic viewing angles to treat challenging lesions such as ostial and bifurcation lesions, or better evaluate the need for plaque modification.

The CT scan is also being used to identify patients for coronary artery bypass surgery without the need for coronary angiography. So, there's been a definite evolution in the CT scan in both structural and coronary fields.

The continued evolution of CT depends on the latest technology reaching the physician and the patient. We are currently in a transition zone where some centres - even big centres - have the previous generation of scanners and there is a big gap in terms of spatial and temporal resolution compared with the latest technology. But when more centres have next-generation equipment, and with more data, I think the world of Al will better inform the physician through the CT scan for both coronary and structural interventions.

What is the strange image in the right ventricle wall? An Amplatz prosthesis!

Submitted by Benjamin Faurie, GHMF, Grenoble, France

1. Agatston AS, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:827-832.

Related content: