Risk of cardiovascular hospital admission after exposure to fine particulate pollution

Selected in Journal of American College of Cardiology by B. Abdulaziz , K. De Silva

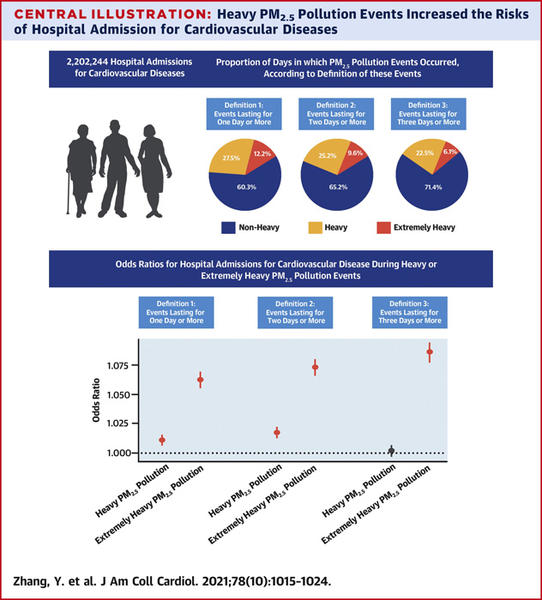

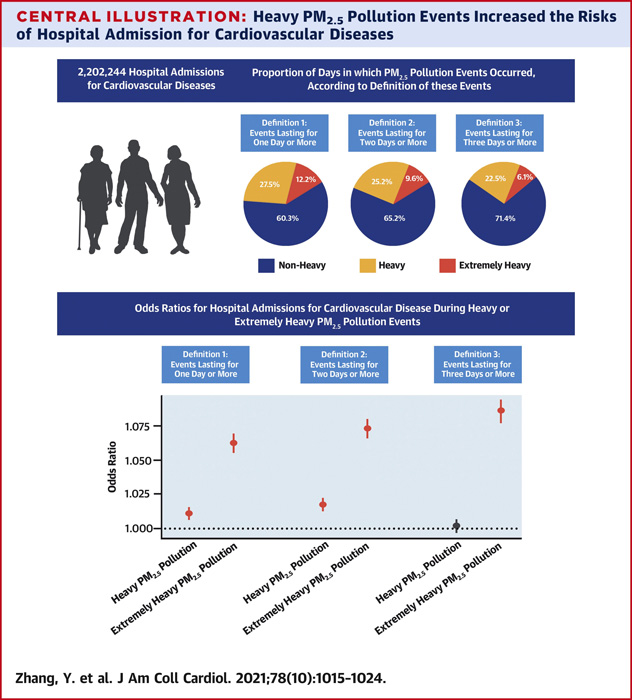

This current study explored the effect of heavy particle pollution on total cardiovascular admissions, whilst also looking at risk for specific cardiovascular diagnoses, such as angina, myocardial infarction, and ischaemic stroke.

References

Authors

Yi Zhang, Runmei Ma, Jie Ban, Feng Lu, Moning Guo, Yu Zhong, Ning Jiang, Chen Chen, Tiantian Li, and Xiaoming Shi

Reference

J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021 Sep, 78 (10) 1015–1024

Published

September 2021

Link

Read the abstract

Reviewers

Our Comment

Why this study – the rationale/objective?

Particulate matter is the term for a mixture of solid particles and liquid droplets found in the air. This encompasses dust, dirt, smoke, as well as finer particles only seen on a microscopic level. Fine inhalable particles (particulate matter of 2.5 micrometres or less – PM2.5) are recognised as highest risk to public health, composed of combustion particles, organic compounds, and fine metals arising from construction sites / smokestacks & fires.

There have been numerous prior studies detailing a suspected link between heavy particulate pollution to all-cause, and specifically, cardiovascular mortality. A previous review from Bell et al1 (2001) looked at hospital admissions and all-cause mortality for the three-month period following the London Fog of 1952 (one of the famous large scale heavy pollution events in modern UK public health) which showed an excess of 12,000 deaths when compared to the previous year’s data.

A previous report from the State of Ecological environment in China2 outlined an issue with heavy air pollution across 338 cities in China, demonstrating 3,113 days of extremely heavy pollution (of which 75 % was PM2.5) over a 5-year period.

This current study by Zhang et al explored the effect of heavy particle pollution on total cardiovascular admissions, whilst also looking at risk for specific cardiovascular diagnoses such as angina, myocardial infarction, and ischaemic stroke. The authors looked to define the association between pollution and cardiovascular admissions.

How was it executed? - the methodology

This was a retrospective observational study undertaken between 2013-2017 in which a case-crossover design was used to explore association between pollution events and cardiovascular admissions; whilst further studying the relationship between varying cumulative lasting days of heavy pollution and cardiovascular admissions.

The pollution data was collected from Beijing, China, obtained from the environmental monitoring centre of Beijing, with data from 35 monitoring stations around the city. The average pollution data from all stations were used to identify the PM2.5 particulate pollution from a single day. These data were subsequently used to create three differing definitions for heavy vs extremely heavy PM2.5 pollution events (varying in particle concentration + consecutive days of such pollution). Definition 1: PM2.5 particle concentration 75-149 µg/m for 1 day or more classified as heavy pollution, whilst particle concentration greater than 150 µg/m classified as extremely heavy pollution. Definitions 2 and 3 were for equivalent concentrations but last 2 days and 3 days respectively.

The authors detailed admission ICD-10 codes relating to specific causes of cardiovascular disease (angina, myocardial infarction, exacerbation of chronic ischaemic heart disease, ischaemic stroke, haemorrhagic stroke, heart failure, arrhythmia, hypertensive heart disease, pulmonary embolism). Admissions rates and an Odds Ratio were calculated for each diagnosis/disease entity, as well as total all-cause cardiovascular admissions rates.

There were 222 days of extremely heavy pollution (> 150 PM2.5 concentration µg/m³) in the timeframe studied from 2013-2017 (59, 52, 49, 40, and 23 days for each year from 2013-2017 respectively). The authors used admissions data on these days (as compared with non-heavy pollution days) to calculate the increase in number of admissions relating to extremely heavy pollution events. This data was further used to calculate estimated increase in annual hospital admissions; as well as total days of inpatient stay relating to extremely heavy pollution.

What is the main result?

The study suggested that heavy (and extremely heavy) pollution events may be an independent risk factor for cardiovascular admissions, over the 5-year period studied. For total cardiovascular disease, the OR under the three definitions of extremely heavy pollution were 1.062 (95 % CI 1.055-1.087), 1.072 (95 % CI 1.065-1.079), and 1.085 (95 % CI 1.077-1.093) respectively.

Under definition 3 (three consecutive days of extremely heavy pollution), the calculated odds ratio (95 % CI) for specific diseases were as follows: angina 1.112 (1.095-1.13), myocardial infarction 1.068 (1.037-1.1), chronic ischaemic heart disease 1.109 (1.078-1.14), ischaemic stroke 1.071 (1.053-1.09), heart failure 1.06 (1.021-1.101), arrhythmia 1.057 (1.026-1.089), hypertensive heart disease 1.086 (1.052-1.12), pulmonary embolism 1.046 (0.0969-1.13) and haemorrhagic Stroke 0.994 (0.952-1.039).

The authors observed an increase in admissions relating to heavy/extremely heavy pollution as compared with non-heavy pollution days (PM2.5 concentration < 75). The calculated average annual admission numbers for cardiovascular disease relating to heavy and extremely heavy pollution events (of 1 day or more) were 1,322 admissions (95 % CI 839 – 1,906) and 3,311 admissions (95 % CI 2,969 – 3,655) respectively. This shows that extremely heavy pollution events overall led to almost a three-fold increase in admission days as compared to heavy pollution days. The data also showed that of these additional admission days relating to extremely heavy pollution, angina accounted for more than 1,000 admissions, with the next most frequent diagnosis encountered being ischaemic stroke at 500 admissions per year.

Annual increase in admission days in hospital relating to extremely heavy pollution (> 150µg/m) was calculated as 37,020 (95 % CI 33,196 – 40,866). Within this, angina made up the largest portion of increased days of admission (> 8,000-day increase in days of admission), as compared for example with arrhythmia and heart failure which made up less than 2,000 increased days each.

Summary of admission burden

Source: Journal of the American College of Cardiology

Critical reading and the relevance for clinical practice

This study asserts that there is positive association between heavy environmental pollution and an increase in cardiovascular disease admissions, though not statistically significant (OR for all-cause cardiovascular disease under definition 3 of heavy pollution and extremely heavy pollution 1.002 & 1.085 respectively). The data also suggested there may be an increased risk of specific cardiovascular diagnoses with an increase in admissions secondary to angina being most prominent.

The authors theorize that it may be the oxidative stress and inflammatory properties of heavy particulate matter entering the body which leads to injury of endothelial cells, as well as causing plaque instability and thrombosis. Although again not meeting statistical significance, this idea would be supported by their findings that haemorrhagic stroke had a lower calculated risk of admission, OR 0.994 (95 %CI 0.952-1.039) under definition 3 of extremely heavy pollution whereas angina (OR 1.112 (95 %CI 1.095-1.13) Myocardial infarction 1.068 (95 % CI 1.037-1.1) Chronic ischaemic heart disease 1.109 (95 %CI 1.078-1.14) events did show an increased risk.

The study also suggests that the duration of pollutant exposure led to increased rates of admission secondary to cardiovascular causes (all diagnoses listed except haemorrhagic stroke). This raises the suggestion that on a public health level, evaluating the duration of exposure (and not only levels of exposure) may be of value in assessing coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndrome provocation risk.

The study model was not able to distinguish whether admission diagnoses were related to a new acute disease process versus an exacerbation of an existing chronic disease, which makes it difficult to define an association between environmental pollution and specific acute cardiovascular pathologies such as acute coronary syndromes.

The generalisability of the data from this study should be considered in the context that the data were obtained from a single city, Beijing. As the authors allude to the healthcare data presented may only be compared/generalised to cities of similar socioeconomic status and population density. Therefore, broader generalisation may not be appropriate, but it reaffirms the general consensus that human-derived emissions and pollutants are likely to have an adverse impact on cardiovascular health and is an important public health issue.

References

- Bell ML, Davis DL. Reassessment of the lethal London fog of 1952: novel indicators of acute and chronic consequences of acute exposure to air pollution. Environ Health Persp. 2001. p389–394

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment. Report on the State of Ecological Environment in China. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China; 2018

No comments yet!