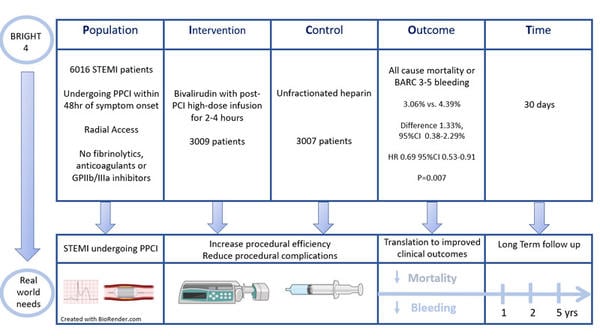

BRIGHT-4 – Bivalirudin plus a high-dose infusion versus heparin monotherapy in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomised trial

Reported from AHA 2022

Nicola Ryan provides her take on the BRIGHT-4 study, which was presented during AHA 2022 in Chicago, & simultaneously published in the Lancet.

This study was a randomised control trial designed to assess if bivalirudin plus a high dose infusion for 2-4 hours post PPCI was superior to unfractionated heparin in patients presenting with STEMI undergoing radial access PPCI.

Why this study – the rationale/objective?

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) is the gold standard treatment for patients presenting with STEMI. Ischaemic and haemorrhagic complications increase morbidity and mortality, therefore managing peri-procedural anticoagulation is key to balance the ischaemic and bleeding risks.

Bivalirudin is a direct thrombin inhibitor and has been posited as an alternative to heparin for anticoagulation during PCI. Initial data suggesting the benefit of bivalirudin above heparin1 was later followed by concerns with regard to increased risk of stent thrombosis2,3, and thus its downgrading in the guidelines4.

It has been suggested that, due to the short half-life of bivalirudin, discontinuation of the infusion immediately post PCI lead to increased stent thrombosis. Furthermore, routine radial access has reduced the bleeding risk associated with femoral access. On this background the authors sought to assess if bivalirudin plus a high dose infusion for 2-4 hours post-PPCI was superior to unfractionated heparin in patients presenting with STEMI undergoing radial access PPCI.

How was it executed - the methodology?

Patients presenting with STEMI with symptom onset within 48 hours undergoing primary PCI via planned radial access were eligible for inclusion.

Major exclusion criteria included administration of heparin, bivalirudin, fibrinolytic therapy of a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor during the current hospitalisation. Bivalirudin was administered as a bolus of 0.75 mg/kg followed by an infusion of 1.75 mg/kg/hr during the PPCI and for 2-4 hours post-procedure.

An additional bolus of 0.3 mg/kg was given if ACT was < 225s five minutes after the initial bolus. Dose reduction was applied for patients with an eGFR < 30mL/min and patients on dialysis. Heparin bolus of 70 IU/Kg was administered with a further heparin if the ACT was < 225s five minutes after the initial bolus. GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors were only permitted for thrombotic complications during the PCI.

- The primary endpoint was a composite of all-cause mortality or BARC type 3-5 bleeding within 30 days of randomisation.

- Secondary endpoints included MACCE (a composite of all-cause death, recurrent MI, ischaemia driven TVR or stroke) and its components, stent thrombosis, BARC types 2-5 bleeding, the composite of all-cause death or BARC 2-5 bleeding, acquired thrombocytopenia and NACE ( the composite of MACCE or BARC types 3-5 bleeding).

What is the main result?

Overall, 6,016 patients were included in the trial, 3,009 randomised to bivalirudin and 3007 to heparin. The majority of patients were male (78 %), with a mean age of 60 years, with a symptom to wire time of 4.5 hrs, two thirds were treated with ticagrelor and one third with clopidogrel.

Radial access was used in 93.1 % of patients, with the majority undergoing PCI (97.9 %) and 90.6 % receiving a drug eluting stent. Tirofiban was used for procedural thrombotic complications in 11.5 % of the bivalirudin group and 13.7 % of the heparin group (difference 2.2 %; 95 % CI 0.5-3.8 %, p = 0.0122). The median peak ACT was higher in the bivalirudin group [321s (IQR 278-365)] compared to the heparin group [267s (238-317].

- The primary endpoint occurred in 3.06 % of the bivalirudin group and 4.39 % of the heparin group (difference 1.33 % ; 95 CI 0.38–2.29 %; HR 0.69 ; 95 % CI 0.53–0.91 ; p = 0.0070) at 30 days.

- All-cause mortality at 30 days was 2.96 % in the bivalirudin group and 3.92 % in the heparin group (HR 0.75 ; 95 % CI 0.57–0.99; p = 0.0420).

- BARC 3-5 bleeding occurred in 0.17 % of the bivalirudin group and 0.8 % of the heparin group (HR 0.21 ; 95 % CI 0.08–0.54; p = 0.0014).

- Stent thrombosis was lower in the bivalirudin group 0.37 % vs 1.1 % (HR 0.33, 95 % CI 0.17-0.66, p = 0.0015).

- NACE was lower in the bivalirudin arm compared to the heparin arm 4.15 % vs 5.55 % (HR 0.74, 95 % CI 0.59-0.94, p = 0.0124)

BRIGHT 4 - PICOT analysis - Courtesy of Nicola Ryan

Critical reading and the relevance for clinical practice

The results of this study show that, in patients undergoing PPCI for STEMI, who did not receive thrombolytics and were not pre-treated with heparin or bivalirudin, bivalirudin with a post-procedure infusion of 2-4 hours resulted in lower all-cause mortality and BARC 3-5 bleeding at 30 days compared to heparin treatment. Bivalirudin resulted in lower stent thrombosis rates with similar rates of ischaemia-driven revascularisation and reinfarction.

Compared to prior trials comparing bivalirudin and heparin, this trial is unique in so far as a post-PCI infusion of bivalirudin was mandated, given that it was hypothesised that the short half-life of bivalirudin meant that its discontinuation immediately post-PCI contributed to increased stent thrombosis observed with bivalirudin.

The bleeding events within the trial were low in both the heparin and bivalirudin groups, with only one major access site-related bleed. The majority of bleeding events were gastrointestinal (heparin 0.57 % vs. bivalirudin 0.13 %, HR 0.23, 95 % CI 0.08-0.70, p = 0.0091).

This trial has a number of limitations including the open-label nature of the trial. Furthermore, the trial was carried out exclusively in China, thus limiting the generalisability to populations worldwide, though there is no known genetic polymorphisms that suggest differing anticoagulant effects.

Furthermore, there are some practical considerations to take into account when considering bivalirudin compared to heparin, including the need for an infusion as well as the increased cost of bivalirudin.

Overall, this trial suggests that bivalirudin is beneficial in terms of reducing all-cause mortality, major bleeding, and stent thrombosis compared to heparin.

Further data with regard to benefit of bivalirudin followed by infusion compared to heparin in more diverse populations will aid in understanding if bivalirudin should be the first-line anticoagulant in PPCI.

References

- Stone GW, Witzenbichler B, Guagliumi G, Peruga JZ, Brodie BR, Dudek D, et al. Bivalirudin during primary PCI in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2008 May 22;358(21):2218–30.

- Shahzad A, Kemp I, Mars C, Wilson K, Roome C, Cooper R, et al. Unfractionated heparin versus bivalirudin in primary percutaneous coronary intervention (HEAT-PPCI): an open-label, single centre, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2014 Nov 22;384(9957):1849–58.

- Steg PG, van ’t Hof A, Hamm CW, Clemmensen P, Lapostolle F, Coste P, et al. Bivalirudin started during emergency transport for primary PCI. N Engl J Med. 2013 Dec 5;369(23):2207–17.

- Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018 Jan 7;39(2):119–77.

No comments yet!