Left main stem percutaneous coronary intervention: does on-site surgical cover make a difference?

Selected in Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions by M. Alasnag , T. Albacker

The current analysis examines patient characteristics and outcomes following LM PCI performed in NSC in England and Wales.

References

Authors

Muhammad Rashid, Mahvash Zaman, Peter Ludman, Harindra C. Wijeysundera, Nick Curzen, Tim Kinnaird, Saadiq Moledina, J. Dawn Abbott, Cindy L. Grines and Mamas A. Mamas

Reference

Originally published18 Oct 2022 - https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.122.012037 - Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2022;15

Published

18 October 2022

Link

Read the abstractReviewers

Our Comment

Why this study – the rationale/objective?

Across the globe, the concept of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in non-surgical centers (NSC) is gaining traction. This is primarily prompted by the need to provide around-the-clock primary PCI for ST-elevation myocardial infarctions (STEMI).

Often, densely populated cities have several established cardiac centers with all the necessary expertise, including cardiac surgeons. In more remote areas, particularly rural areas, stand-alone catheterization laboratories are constructed with limited availability of surgically equipped centers and trained cardiac surgeons to cover large territories providing primary PCI programs.

The Atlantic CPORT study (Cardiovascular Patient Outcomes Research Team (CPORT) Non-Primary PCI ), published a decade ago, enrolled 18,867 patients who were randomly assigned to undergo PCI at a hospital without on-site cardiac surgery (14,149 patients) or with on-site cardiac surgery (4,718 patients). At 6 weeks, the mortality rate was 0.9 % for those who underwent PCI in hospitals without on-site surgery, compared with 1.0 % for those who underwent PCI in hospitals with on-site surgery (95 % confidence interval (CI) −0.31 to 0.23; P = 0.004 for non-inferiority). The 9-month rates of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) were 12.1 % and 11.2 % respectively (95 % CI, 0.04 to 1.80; P = 0.05 for noninferiority)1.

Since then, it has been deemed safe to perform PCI in NSC. Although, upon close scrutiny, the centers without onsite cardiac surgery had a higher rate of PCI failure, higher incidence of unplanned recatheterization and PCI before discharge, as well as a higher incidence of unplanned revascularization at 6 weeks and 9 months. In addition, when an intention-to-treat protocol was used and CABG was not counted, NSC was non-inferior to (surgical centers) SC. However, when the per-protocol analysis was performed, a higher rate of MACE in NSC was detected. These differences were within the non-inferiority margins; nevertheless, they warrant a pause.

Over time, NSC have also offered complex PCI for non-urgent cases such as Left Main (LM) PCI. A more recent large meta-analysis by Lee et al noted that for non-primary PCI the all-cause mortality was 1.6 % versus 2.1 % (95 % CI 0.94–1.41; P = 0.172) and emergency CABG was 0.5 % versus 0.8 % (95% CI 0.62–2.13; P = 0.669) in NSC vs. CS centers. PCI complication rates, including cardiogenic shock, stroke, aortic dissection, tamponade, and MI, were similar2. This data is valuable given that it reflects more contemporary practices and stent platforms.

The current analysis by Rashid et al more specifically examines patient characteristics and outcomes following Left Main (LM) PCI performed in NSC in England and Wales3.

How was it executed – the methodology?

This was a retrospective analysis of all PCIs extracted from the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society database between January 2006 and March 2020.

The population was stratified according to the status of surgical coverage.

In-hospital major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE), all-cause mortality, and Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) stage 3 to 5 bleeding were the reported primary endpoints.

Logistic regression models were used to determine the association between the availability of on-site surgery and in-hospital adverse outcomes such as mortality, MACCE, BARC 3 to 5 bleeding, and emergency CABG.

Investigators also sought to identify predictors of in-hospital mortality.

Adjustment for age, sex, date, clinical presentation including shock, previous MI or revascularization, and other co-morbidities including diabetes, renal failure, peripheral vascular disease, and cerebrovascular accidents, was performed.

What is the main result?

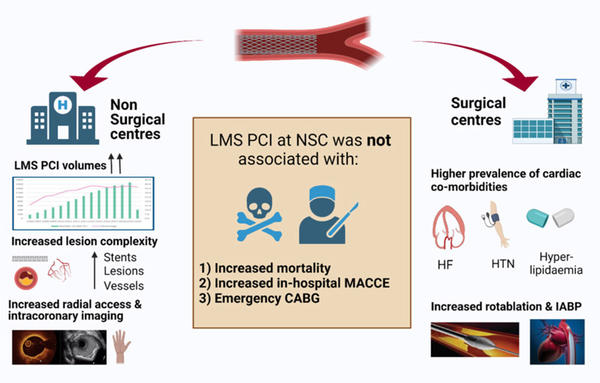

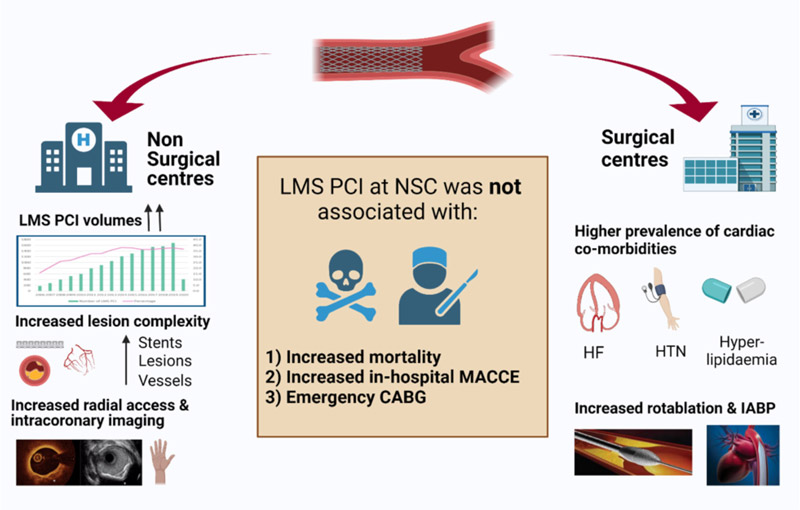

This was the largest cohort of patients undergoing LM PCI worldwide (40,744 patients) of whom 13,922 (34.2 %) had the PCI performed at an NSC.

In terms of baseline characteristics, the mean age was 70 years, with the majority enrolled being men (approximately 72 %).

There were notable baseline differences between the two groups whereby the SC group had more comorbidities, such as hypertension, renal disease, hyperlipidemia, and depressed left ventricular function. The NSC group was more likely to present with stable disease and have prior PCI.

Interestingly, centers with off-site surgeons were more likely to use radial access and intravascular ultrasound. It appears SC received and managed more shock patients (12.3 % versus 11.4 %) and had more frequent use of intra-aortic balloon pumps (9 % versus 6.8 %).

What is also evident is that the number of LM PCI performed in NSC doubled from 2006 to 2020 (15.9 % and 36.7 % respectively) in the United Kingdom, with the majority being elective.

In-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 0.92 [95 % CI, 0.69–1.22]), in-hospital MACCE (odds ratio, 1.00 [95 % CI, 0.79–1.25]), or emergency CABG (odds ratio, 1.00 [95 % CI, 0.95–1.06]) was similar.

Interestingly, NSC had lower BARC 3 to 5 bleeding complications (odds ratio, 0.53 [95 % CI, 0.34–0.82]).

Left Main Stem PCI: does onsite surgical cover make a difference? - Source: Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions

Critical reading and relevance for clinical practice

The data presented in this large analysis from the UK indicates that LM PCI in centers without on-site surgical backup is safe. It also demonstrates the proficiency of operators in NSC in contemporary practices such as radial access and intracoronary imaging which likely drove the good outcomes in NSC.

Although the SC had a higher rate of comorbidities, lower ejection fraction, and higher use of atherectomy, it appears that more vessels were treated in the NSC group.

Without assessing the Syntax scores (and residual Syntax score), it is difficult to ascertain the completeness of revascularization or to capture the true complexity of the LM disease treated in either arm. Additionally, lack of onsite surgical coverage does not necessarily mean the absence of heart team discussions with surgical representation, which was not clarified in this study.

This is of course data from the UK only and, although convincing, it cannot be extended to other countries with different healthcare systems and transfer policies. In addition, these results may not be applicable to low-volume operators in remote centers with little exposure to complex PCI with the anticipated bailout equipment or techniques.

Given the retrospective design of the study, it is difficult to tease out the reason for treating more lesions and stenting more patients with 3 vessels in NSC and having more emergency CABG in SC. Could that be the bailout option for NSC to stent more lesions as compensation for the lack of surgical coverage?

Additionally, the investigators did not include a separate analysis of outcomes of those patients requiring emergency CABG that would illustrate if there would be a price for transferring patients to different sites with surgical expertise. A very recent analysis by Waldo et al reported outcomes from the Veteran Affairs Healthcare system of 75,564 patients who had undergone PCI, 71 % of whom were treated at sites with surgical backup. They note that the overall complexity of those treated at SC was higher than those at sites without surgery (P < 0.001). However, the referrals for emergent cardiac surgery were rare and similar in both groups after propensity matching. In essence, this may suggest better selection of sites and referral of more complex anatomies to centers with surgical backup4.

Additionally, an important limitation of this study would be the long-term outcomes, particularly those with more complex disease and higher syntax scores.

Although the totality of evidence suggests that PCI (primary and complex) in NSC is safe, there is no doubt that timely surgical bailout is a key determinant of outcomes and should be factored into the decision-making.

PCI in NSC should require a thorough heart team discussion, particularly for elective cases, which today could take the form of virtual sharing of the angiograms and conversations. Should PCI in NSC only include centers where short transfer times and transportation systems are in place for unstable patients following a complication? Should informed consent include PCI in a center without on-site surgery? These are integral questions that we should be asking.

Finally, permitting complex PCI, including LM, in NSC could decompress waiting times and provide volume for training centers in remote areas, if done properly, with an appropriate heart team structure and documented discussion.

A counterargument would be to enable trainees a more comprehensive program in large centers with surgical and percutaneous revascularization. Given that the current guidelines essentially limit the role of PCI for LM disease to those with a low Syntax score affording it a Class 2a recommendation, the volume of LM PCIs would be limited and could ultimately impact the competency of trainees by diluting their exposure5-6.

References:

- Aversano T, Lemmon CC, Liu L; Atlantic CPORT Investigators. Outcomes of PCI at hospitals with or without on-site cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2012 May 10;366(19):1792-802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114540. Epub 2012 Mar 25. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2012 Apr 26;366(17):1650.

- Lee JM, Hwang D, Park J, Kim KJ, Ahn C, Koo BK. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention at Centers With and Without On-Site Surgical Backup: An Updated Meta-Analysis of 23 Studies. Circulation. 2015 Aug 4;132(5):388-401. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016137. Epub 2015 Jul 7.

- Rashid M, Zaman M, Ludman P, Wijeysundera HC, Curzen N, Kinnaird T, Moledina S, Abbott JD, Grines CL, Mamas MA. Left Main Stem Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Does On-Site Surgical Cover Make a Difference? Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022 Oct;15(10):e012037. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.122.012037. Epub 2022 Oct 18.

- Waldo SW, Hebbe A, Grunwald GK, Doll JA, Schofield R. Clinical and Anatomic Complexity of Patients Undergoing Coronary Intervention With and Without On-Site Surgical Capabilities: Insights From the Veterans Affairs Clinical Assessment, Reporting and Tracking (CART) Program. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2021 Jan;14(1):e009697. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.120.009697. Epub 2020 Dec 23.

- Writing Committee Members, Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, Bates ER, Beckie TM, Bischoff JM, Bittl JA, Cohen MG, DiMaio JM, Don CW, Fremes SE, Gaudino MF, Goldberger ZD, Grant MC, Jaswal JB, Kurlansky PA, Mehran R, Metkus TS Jr, Nnacheta LC, Rao SV, Sellke FW, Sharma G, Yong CM, Zwischenberger BA. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Jan 18;79(2):e21-e129. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.006. Epub 2021 Dec 9. Erratum in: J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Apr 19;79(15):1547.

- Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, Alfonso F, Banning AP, Benedetto U, Byrne RA, Collet JP, Falk V, Head SJ, Jüni P, Kastrati A, Koller A, Kristensen SD, Niebauer J, Richter DJ, Seferovic' PM, Sibbing D, Stefanini GG, Windecker S, Yadav R, Zembala MO. Linee guida ESC/EACTS 2018 sulla rivascolarizzazione miocardica. Task Force sulla Rivascolarizzazione Miocardica della Società Europea di Cardiologia (ESC) e dell’Associazione Europea di Chirurgia Cardiotoracica (EACTS) [2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. The Task Force on myocardial revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)]. G Ital Cardiol (Rome). 2019 Jul-Aug;20(7-8 Suppl 1):1S-61S. Italian. doi: 10.1714/3203.31801.

No comments yet!